A Stigler Center panel debates: Is rising inequality connected to monopolies, rent-seeking, and concentration?

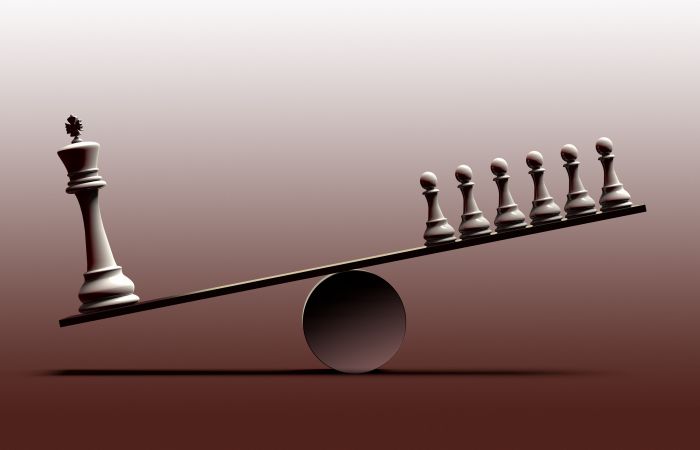

The rise in wealth and income inequality has been at the forefront of the political debate in the U.S. in the last few years. At the same time, issues like market power and concentration, bigness, and antitrust have also come back into prominence, propelled by a growing body of research that points to diminishing competition across multiple American industries.

The possible connection between inequality and market concentration, however, has been relatively understudied for many years—until recent years, that is, when a sheaf of new studies examining the interactions between concentration, market power, and inequality began to appear.

A 2015 paper by Jonathan Baker and Steven Salop, for instance, examined the connection between inequality and market power and argued that “because the creation and exercise of market power tend to raise the return to capital, market power contributes to the development and perpetuation of inequality.” Harvard Law School’s Einer Elhauge also found that horizontal shareholding likely leads to anti-competitive price raises and has regressive effects. Daniel Crane of the University of Michigan, however, contends that the connection between antitrust and wealth inequality has been grossly oversimplified by advocates of tougher antitrust enforcement.

Is rising inequality connected to monopolies, rent-seeking, and concentration, or is it a result of larger forces like globalization and technology? Can antitrust be used effectively to mitigate inequality, or is concentration a sign of greater efficiency? These questions, and others, were debated by economists and legal scholars during a panel at the recent Stigler Center conference on concentration in America.

The panel featured Peter Orszag, Vice Chairman and Managing Director of the financial advisory and asset management firm Lazard Freres; Justin Pierce, a Senior Economist at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve; Lina Khan, a fellow at Open Markets program at New America; Sabeel Rahman, an Assistant Professor of Law at Brooklyn Law School; Simcha Barkai, a PhD Candidate at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business; and German Gutierrez, a PhD Candidate at the New York University Stern School of Business. The panel was moderated by Matt Stoller of the Open Markets program at New America, who opened by observing that “a new kind of Brandeis School of antitrust is emerging, in terms of thinking about political economy.”

Much of the panel focused on the dramatic rise in corporate profits. A recent, much-discussed Stigler Center working paper by Simcha Barkai found that over the past 30 years, as labor’s share of output fell by 10 percent, the capital share declined even further. This finding goes against the argument that the labor share went down due to technological changes, or as Barkai put it: “We used to spend money on people, today we’re spending money on robots.”

Barkai’s paper finds no evidence to support the technological argument. “We’re spending less on all inputs. If you think of this from the perspective of a firm, this is terrific. After accounting for all of my costs—material inputs, workers, capital—I am left with a large amount of money, much more so than in the past.” What Barkai does find, however, is that profits have gone way up. From 1984 to 2014, the profit share increased from 2.5 percent of GDP to 15 percent.

“To give you a sense of how large these profits are, if you look over the past 30 years and you ask, ‘How much have profits increased?’ you can give a number in dollars. A better way to think about that is, “Per worker, how much have these dollars increased?” It’s about $14,000 per worker. That’s a really large number because, in 2014, personal median income was just over $28,000. It’s about half of personal median income,” said Barkai.

Barkai went on to say that these findings were more pronounced in industries that experienced an increase in concentration. “Those industries that have a large increase in concentration also have larger declines in the labor share,” he said. Barkai’s conclusions were echoed by a separate study that was recently published by David Autor, David Dorn, Lawrence Katz, Christina Patterson, and John Van Reenen, in which they found that higher concentration is connected to the fall in the labor share.

One way to consider the question of concentration and inequality, said Pierce, is to look at what happens to firms’ efficiency and markups as a result of a merger. In a recent paper with Bruce Blonigen, Pierce was able to utilize new techniques in order to isolate the effects of mergers in the manufacturing sector. Comparing data from factories that were acquired during mergers to similar factories that weren’t, and to factories where an acquisition has been announced but not yet completed, Pierce and Blonigen found no evidence of the standard argument that mergers benefit consumers by increasing efficiency, reducing production costs, and, in turn, lowering prices. Quite the opposite: they found evidence that mergers increase market power, allowing firms to generate higher profits by raising prices.

“What we find when we do this is that mergers on average are associated with increases in markups in a magnitude of 15 to 50 percent. When we look at the effect on productivity, we actually don’t find a statistically significant effect on productivity associated with mergers,” said Pierce.

Gutierrez, meanwhile, spoke about his 2016 paper with Thomas Philippon, in which the two found that concentrated industries with less entry and more concentration invest less. Before 2000, he explained, firms funneled about 20 cents of every dollar of surplus into investments. Since 2000, however, investments dropped by half—to 10 cents on the dollar.

Their findings, he said, rule out the argument that the drop in investments is related to control by the stock market. The data also rule out other theories, such as financial constraints, safety premiums, or globalization. “What we’re left with is competition, or lack of competition and governance,” said Gutierrez.

“What we find is that most industries have become more concentrated. That leads to a decrease in investment. It means less investment by leaders in particular, and at the industry as a whole. Some manufacturing industries have seen increased competition from China. For the U.S. in particular, we see that leaders invest more. They try and hold onto their position, but the overall effect is somewhat negative on aggregate investment in the U.S.”

How is this drop in investments connected to an increase in concentration? Gutierrez offered two hypotheses: one, that superstar firms, such as digital platforms, are more productive and are therefore capturing more market share. The second, he said, is increased regulation: “In particular, if you look at the cross section of industries, industries where regulation has increased have also tended to become more concentrated and have invested less.”

Orszag, the former head of the Office of Management and Budget and former Director of the Congressional Budget Office, co-authored a 2015 paper with former Obama economic adviser Jason Furman that explored the rise in “supernormal returns on capital” among firms that have limited competition. In the panel, he spoke about what he described as a “dramatic rise” in dispersion among firms in productivity and wages as an understudied driver of inequality.

“In general, if you look at most textbooks on economics and most discussions of public policy, firms are seen as this uninteresting thing that you have to deal with but don’t want to really get into the innards of. Why do some firms behave differently than others? Having now spent a bunch of time in the private sector, the culture in firms really is quite different. Firms do behave differently from one to another beyond just market structure. Within the same market in the same field, Firm A is not the same as Firm B, as people who work inside those firms know.”

Orszag pointed to OECD data that showed that top global firms have been largely exempted from the decline in productivity that advanced economies experienced over the last 10-15 years. “If there’s a structural explanation for that, whether it’s polarization or market structure or innovation, why is it affecting only the laggards in the industry and not those at the frontier? Secondly, why aren’t there more spillovers from the frontier firms within each sector to others? What is happening to the flow of information or the flow of technique or what have you that’s causing this broad, significant rise in productivity deltas across firms, even within the same sector?” he asked.

Orszag also suggested that contrary to media narratives that present growing gaps between CEO wages and median workers within each firm as a prominent driver of inequality, the bulk of the rise in wage gaps is happening between firms, and not within the firms themselves. Studies, he said, show a dramatic increase in between-firm wage inequality “and very little movement except at the very, very largest firms in within-firm inequality.”

Orszag added: “We don’t know exactly what’s causing this. This may be a sorting of workers. It may be sharing of rents in the form of wages for the top firms. It may be a whole variety of different things. What I do suggest is the vast majority of the discussion on income-and-wage inequality seems to just glide over this whole thing as if it doesn’t exist.”

A holistic approach to inequality and concentration

Khan, who in a recent paper with Sandeep Vaheesan explored the role of monopoly and oligopoly power in perpetuating inequality, argued that the way to understand the connection between market concentration and inequality is to take a more holistic approach.

The connection between excessive market concentration and inequality, she said, has been understudied for a long time. “We were really surprised to see that at the time, in 2014, there really wasn’t much research on this connection at all. The most comprehensive paper that we found was from 1975 by William Comanor and Robert Smiley, which found that monopoly power did in fact transfer wealth to the most affluent members of society and suggested that a more competitive economy would have more progressive redistributive effects,” said Kahn. “One way to understand why this connection between market concentration and inequality has been understudied is that the law decided that it wasn’t really important. Once we shifted from an antitrust approach that took a more holistic and multidimensional view of the effect of market power to an approach that privilege means prices, the research on these effects also took a hit.”

In their paper, Khan and Vaheesan argue that inequality not only harms efficiency, but also that firms use their market power to raise prices “above competitive levels to consumers and push prices below competitive levels for small producers.” The paper makes a case for more rigorous enforcement of antitrust laws, arguing that reinvigorating antitrust could be one possible remedy for the regressive redistributive effects of concentration and the political power of monopolies.

“I think at a very basic level, our current political economy reflects 30 years of doing antitrust in a very particular way,” said Khan, who listed several industries such as airlines, healthcare, pharmaceuticals, and telecom, where prices have risen following mergers and industry consolidation.

“New business creation and growth have been on a secular decline. It’s worth recalling that in an earlier era, owning one’s own business was a form of asset building for the middle class, a way of passing on wealth to one’s children. This is especially still true in immigrant communities, where owning your own bodega or your own dry-cleaning service is a path of upward mobility. You can imagine how markets that shut out independent businesses are also effectively closing off that path of asset building,” said Khan.

Khan went on to discuss the political implications of excessive market power and how they can further entrench inequality. “Big firms and concentrated industries enjoy a level of political power that they can use to further entrench their economic dominance. Politics is another vessel by which we see this,” she said.

Rahman, author of the book Democracy Against Domination (Oxford University Press, 2016), also advocated for a wider view of the issue. “When we’re worried about the problem of concentration, I think it goes much broader than the specific areas of mergers and firm size, although that’s a big part of it,” he said.

“When we think about the good things that we want from the economy, we want it to be dynamic, we want it to be innovative, we want it to enable mobility. These things are not natural products. They are a property of the underlying structure of firms, of labor markets, of financial markets, and of policies, including antitrust,” said Rahman, who went on to discuss two aspects of the rise in concentration: digital platforms and the “Uber-ization” of more and more economic sectors, and what he described as a “growing geographic concentration of wealth, income, and opportunity between rural and urban.”

Rahman suggested that other tools, not just antitrust, could be used to combat excessive market power—particularly when it comes to the power of digital platforms. “The way I want to frame this is as a problem of concentration and inequality that warps the structure of opportunity in our economy,” said Rahman. “You have antitrust and public utility law, corporate governance, and labor law as three parts of the larger ecosystem of law and regulation that, coming out of that Progressive era debate about power, were the three complements that together, it was hoped, would produce a high-opportunity, a high-mobility economy that was open to all.”