Can direct democracy be used to fix the crisis of representative democracy? Join us for a series of three stand-alone, interrelated lunch seminars by University of Southern California professor John Matsusaka.

Following a year in which a surge of populist politics threatened to engulf Western democracies, Emmanuel Macron’s decisive victory over the far-right Marine Le Pen in the French presidential election has elicited a wave of relief around the world. The fact that a pro-globalization centrist like Macron was able to defeat Le Pen by a huge majority of 66 to 34 percent, along with the earlier loss of the far-right Geert Wilders in the Netherlands, led some to speculate that the wave of populism that culminated in Brexit and the election of Donald Trump in 2016 has been thwarted.

Others, however, warned that the forces that fueled anti-establishment discontent are unlikely to disappear anytime soon. The populist threat to liberal democracy, wrote Harvard’s Yascha Mounk, stems from “deep, structural causes.” Some of those causes have been discussed by scholars in ProMarket’s interview series on the economic theory of the firm: rising inequality, economic insecurity, globalization, technological change, and the sense that governments’ failure to address these issues means that the system is “rigged.”

Another cause, explored by Mounk in a recent paper with Roberto Stefan Foa, is that liberal democracy itself is undergoing a major existential crisis, as more and more citizens of democracies around the world are losing faith in democratic institutions, becoming “markedly less satisfied with their form of government and surprisingly open to non-democratic alternatives.” Signs of declining support for democracy, they found, can be seen in numerous countries, like Australia, Britain, Sweden, and the United States, particularly among young people.

One potential response to this democratic crisis is a more direct form of democracy. As political systems across the West have been crippled by increasing polarization and fragmentation, support for more direct alternatives to representative democracy has increased, leading to the rise of Pirate Parties that extol the virtues of direct democracy.

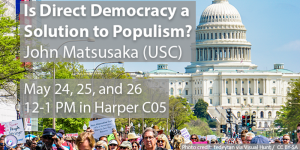

Is direct democracy a solution to populism, and can it be used to fix democracy? Later this month, University of Southern California professor John Matsusaka will visit the Stigler Center for a series of three stand-alone, interrelated lunch seminars that focus on these very questions:

-

Wednesday, May 24: Are the People Losing Control Over the Institutions They Elect?

-

Thursday, May 25: Why Direct Democracy Can Work

-

Friday, May 26: Can We Use Direct Democracy to Fix Democracy?

Matsusaka, the Charles F. Sexton Chair in American Enterprise in the the Marshall School of Business, Gould School of Law, and Department of Political Science at USC, has previously served as a consultant for the White House Council of Economic Advisors and is the author of For the Many or the Few: The Initiative, Public Policy, and American Democracy (University of Chicago Press, 2004). His research focuses on the financing, governance, and organization of corporations and governments. In his Stigler Center lectures, Matsusaka will discuss the possible reasons for the rise of global populism and explore the role of direct democracy—in the form of initiatives and referendums—as an alternative to representative democracy.

All seminars will take place between 12 p.m. and 1 p.m. in the room C05 of Harper Center at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business (5807 S. Woodlawn Ave., Chicago, IL 60637). Register here.