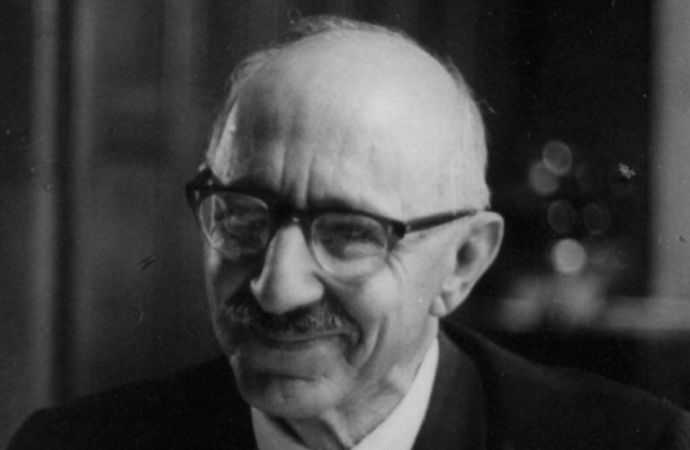

David Henderson of the Hoover Institution defends the legacy of Aaron Director, the most enigmatic among the founders of the so-called “Chicago School.” Director, argues Henderson, was not the nihilist Matt Stoller accused him of being.

Editor’s note: Aaron Director, one of the founders of the so-called Chicago School of Law and Economics, died 15 years ago. To mark the anniversary of his death, ProMarket is publishing a series of articles on his work and controversial intellectual legacy. In response to Matt Stoller’s highly-critical article on Director, the Hoover Institution’s David Henderson reacted with a piece originally published in Econlib. We are republishing it here with Matt Stoller’s reply below.

Aaron Director was one of the founders of law and economics: the application of economic reasoning to understand the effects of law and, in some cases, to recommend particular laws. He wrote very little, but his influence was immense.

Director was best friends with George Stigler, brother of Rose Director Friedman, and brother-in-law of Milton Friedman.

I interviewed him in the late 1990s and Milton Friedman showed some of that interview at Aaron’s memorial service at the Hoover Institution.

If I were asked to characterize Director’s views, I would say that he was someone who cared a lot about freedom and thought that freedom for everyone would particularly benefit taxpayers and consumers. That doesn’t mean he was right, although I think he was. But I think that’s what animated him.

But that’s not what Matt Stoller thinks. On the blog of the Stigler Center last week, the center named after Aaron Director’s best friend, Matt Stoller writes what can be reasonably be described as a hatchet job on Director, not just going after his ideas but also going after Director’s motivations. The post is titled How Powerful Ideas Can Shape Society: Aaron Director and the Triumph of Nihilism. Here are some quotes from Stoller about Director and about economics with my comments afterward.

“Director’s life was dedicated to setting free the power of concentrated capital, eliminating the power of labor, and undoing the New Deal. His success is so profound it is hard to describe, so embedded are we today in the world and rhetoric Director shaped.”

Actually, Director was a strong believer in competition, which, Stoller might not know, tends to undercut the power of concentrated capital. It is true, I think, that Director wanted to eliminate “the power of labor” to the extent that that was monopoly power granted to labor unions by federal law. One example: when workers in a workplace organize into a union, all of the workers (not management), whether they’re members or not, are part of the collective bargaining agreement; they can’t bargain for themselves.

“Banks were strictly controlled, with the largest banks in New York City prohibited from even opening branches outside of the five boroughs.”

In context, Stoller is saying this is good because he thinks big corporations are bad. He probably would be surprised to know that the restrictions on branch banking were part of the reason that the Great Depression was “great.” That fact is familiar to economic historians who study the Great Depression, but not, apparently, to Stoller.

“Director made his final turn in 1950. Simons and Hayek both saw corporate monopolies as dangerous, perhaps even more dangerous than big government or labor unions. And Director was a great admirer of Simons, whose Positive Program for Laissez Faire was as antimonopoly as it was anti-big government. But Simons killed himself in 1946. And the extreme right-wing funder of the project, Harold Luhnow of the Volker Fund (who later dallied with fascists in the 1960s), essentially threatened to fire Director if he didn’t jettison his allegiance to Simons’s anti-corporatist ideas.

Director suddenly decided that conservative ideas were compatible with corporatism after all. Monopolies, apparently, were always created by government. At this moment, Director broke with the conservative tradition and birthed neoliberalism, the anti-government, pro-monopoly philosophy that now dominates policymaking globally. Director convinced George Stigler and Milton Friedman of the new creed. Both had opposed corporate monopolies, but flipped to support Director’s new movement. The Chicago School was born.”

Get it? Director didn’t come to his free-market views because he thought they made sense. Oh, no. He “suddenly” came to them because, hints Stoller, Harold Luhnow threatened to fire Director if he didn’t. Oh, and those two friends, George Stigler and Milton Friedman? They “flipped.” And apparently their “flipping” had little to do with looking at arguments and evidence.

And “the anti-government, pro-monopoly philosophy” dominates policymaking globally. Trump’s tariffs, to take a recent example, are admittedly pro-monopoly, but they’re hardly anti-government. A lot of pro-monopoly policies are pro-government. Think of the almost total government monopoly of K-12 schooling, for example.

“Throughout this ideological journey, Director remained a Mencken-ite above all, a man who believed that some were fit to rule, and others to be ruled. He didn’t characterize it this way, instead using the term ‘economist’ to mean those fit to speak the language of power. But that was his framework, and in many ways, it is still the framework by which antitrust insiders think about who gets to have opinions in dialogue about political economy.”

The idea that some were fit to rule and others to be ruled fits Franklin D. Roosevelt more than it fits Director. Director was not a full-fledged libertarian but he did believe in a fair amount of freedom for everyone. The ultimate in freedom is that no one is ruled.

To his credit, Stoller does raise some concerns about one of Director’s most important accomplishments: getting the young John S. McGee to go through the transcripts of the famous Standard Oil case to see if it was indeed true that Rockefeller engaged in predatory pricing. McGee found that it wasn’t, but Stoller cites a long law review article by Chris Leslie that raises some doubts about this.

Here are Stoller’s last two paragraphs:

“Director’s impact is undeniable. I started out researching Director’s role in the rise of law and economics with a belief that there was a good faith attempt to wrestle with flaws in what perhaps was an overwrought New Deal structure. But what I realized, after seeing how he constructed a brilliant and intellectually dishonest political movement to attack the ability of democratic institutions to touch economic questions, is that Director modeled himself after Mencken. He was a nihilist and an elitist, and so was his movement.

Today’s America, where lifespans are declining, where giants like Google and Amazon stride across the land unchallenged, where big banks crush the economy and bring forth men like Donald Trump to lead, is Director’s legacy. It is a legacy of nihilism and hopelessness. I admire his stunning ability to build political power and transform society. But truthfully, I could never really understand why he sought to use them towards such wretched ends.”

I don’t know that it’s true that Stoller “could never understand” why Director used his ability the way he did. I bet he could understand. But what’s clear is that he doesn’t. To understand, Stoller would have to understand better what Director’s ends were. They were not wretched.

Matt Stoller’s Reply to David Henderson:

Thanks for David’s critical response. I would like to offer a source for one part of my argument, which was the influence of Volker money. I drew that from an essay by Robert Van Horne in The Road from Mont Pèlerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective, With a New Preface (pp. 208-209, Harvard University Press 2009, Kindle Edition). Here’s the relevant excerpt:

“Before turning to a detailed description of the FMS and its undertakings, it is important to keep in mind that reconceptualization of liberal doctrine at the University of Chicago occurred under external solicitation from a politically motivated benefactor, the Volker Fund.

The Volker Fund bankrolled both the FMS and the Antitrust Project, as well as a myriad of future research projects at Chicago, and directly exerted its influence throughout the duration of those projects. During the middle years of the FMS (around 1950), the Volker Fund went so far as to threaten to eject Director from his leadership role in the FMS because the Volker Fund refused to accept certain tenets of classical liberalism, namely those espoused by the deceased Chicago economist Henry Simons.

As the FMS wound down, in 1951, Jacob Viner—a classical liberal and renowned economist who left Chicago for Princeton in 1946—recollected his experience at a Volker-funded conference headed by Director and Levi at the Chicago Law School:13 “[Everything] about the conference except the unscheduled statements and protests from individual participants were so patently rigidly structured, so loaded, that I got more amusement from the conference than from any other I ever attended . . . even the source of the financing of the Conference, as I found out later, was ideologically loaded.”

David Henderson is a professor of economics at the Graduate School of Business and Public Policy, Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California and a Research Fellow with the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. Matt Stoller is the author of the upcoming book Goliath: The Hundred Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy and a fellow at the Open Markets Institute.

The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.