The final installment of our four-part series on the history of antitrust language in American political discourse.

In the fourth and final installment of our four-part series on the history of antitrust language in American political discourse, we review the evolution of economic language related to trusts and antitrust in all Democratic and Republican platforms from the end of WWII until today.

Read previous installments: first, second, and third.

“One of the biggest problems facing America’s economy is waning competition. In the home of free enterprise two-thirds of industries have become more concentrated since the 1990s, partly owing to lots of mergers. Fat, cosy incumbents hoard cash, invest less, smother new firms that create jobs and keep prices high. They are rotten for the economy.”

This is the opening paragraph of an October 26 article in The Economist–not only one of the most read and influential newspapers worldwide, but also a staunch pro-business advocate.

The article, which opposes the AT&T-Time Warner deal, goes on to say that “boosting competition should be a priority for whoever occupies the White House in 2017, and for Congress. Now a test case is waiting in the in-tray. AT&T, America’s fifth-biggest firm by profits, wants to buy Time Warner, the second-biggest media firm. The $109bn megadeal isn’t a simple antitrust case, because it involves a firm buying a supplier, not a competitor. But there is a strong case that it will limit consumer choice in a part of the economy that is rife with rent-seeking and extend a worrying concentration of corporate power. It should be stopped.”((“Vertical limit.” Economist, October 2016.))

In the last installment of this series, we analyzed the language in Republican and Democratic platforms regarding these issues in the period leading up to the end of WWII. In this last part, we will focus on the years since WWII.

FDR’s presidency marked the end of a decades-long emphasis by the federal government on antitrust and regulation, starting with the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890.

WWII commanded much of FDR’s attention. The following years were, in large part, focused on rebuilding the US domestic economy as well as its new status as leader of the free world.

Until the 1970s, U.S. antitrust policy and enforcement were still largely based on the legislation and case law that accumulated from as far back as the Sherman Antitrust Act. Notwithstanding, in 1950, during Harry S. Truman’s presidency, Congress passed another major antitrust law, the 1950 Celler-Kefauver Act. The act closed a loophole in existing legislation that enabled businesses to merge by buying the assets of their competitors rather than buying their stock.

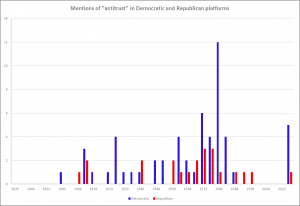

Throughout the 1970s, Democratic platforms were still more prominent in advocating for antitrust:

Democratic platform, 1960 (Richard Nixon v. John F. Kennedy):

“Democratic Congresses have enacted numerous important measures to strengthen our anti-trust laws. Since 1950 the four Democratic Congresses have enacted laws like the Celler-Kefauver Anti-Merger Act, and improved the laws against price discriminations and tie-in sales. When the Republicans were in control of the 80th and 83rd Congresses they failed to enact a single measure to strengthen or improve the antitrust laws. The Democratic Party opposes this trend to monopoly. We pledge vigorous enforcement of the antitrust laws.”

Democratic platform, 1972 (Richard Nixon v. George McGovern):

“[under Toward Economic Justice] Step up anti-trust action to help competition, with particular regard to laws and enforcement curbing conglomerate mergers which swallow up efficient small business and feed the power of corporate giants; Strengthen the anti-trust laws so that the divestiture remedy will be used vigorously to break up large conglomerates found to violate the antitrust laws;”

However, owing to major advancements in economic theory, the proliferation of mergers that led to a growing body of evidence, and the first steps of computerization, the thinking behind antitrust was heade

d for a major overhaul.

In 1968, the Department of Justice issued Merger Guidelines, which eventually were revised multiple times. The document was developed by former U.S. Assistant Attorney General Dr. Donald Turner, a lawyer who was also an economist and was considered an expert on industrial organization theory. Not surprisingly, the guidelines bore his industrial organization theory viewpoint.((See the 1968 Merger Guidelines here))

During these years, a new school of thought that was more focused on microeconomic theory, market power, market structure, cost savings, and other issues that differ from industrial organization theory, started to develop.

This school of thought was later nicknamed the “Chicago School” because many of its developers were members of the economics department of the University of Chicago. The Chicago School proved to be a hotbed for Nobel laureates, such as Milton Friedman, Gary Becker, Eugene Fama, and George Stigler. Of these scholars, Stigler’s contribution to antitrust and regulation was the most influential.

Stigler argued that basic microeconomic theory is the tool for analyzing the structures of industries. As John Kwoka and Lawrence White wrote in their book The Antitrust Revolution: Economics, Competition, and Policy (Oxford University Press, 2013, 6th edition), Stigler and others:

“…argued, for example, that mergers should be analyzed in terms of both their likely price effects and the plausible cost savings achieved by the merged company. They further claimed that price increases are not so easy to achieve, either because of the inherent difficulty of tacit cooperation or because of ease of entry by new competitors. For these reasons mergers were said to be generally pro-competitive, and not properly evaluated with such indicia as market shares and industry concentration. On other issues, the Chicago School was equally adamant. Price cuts were said almost invariably to reflect lower costs and legitimate competitive behavior rather than predation. Efforts by manufacturers to establish retail prices or to constrain the behavior of independent retailers, that school argued, almost always represent efforts to control certain aspects of the sale in which the manufacturers have a legitimate interest. The different perspective of the Chicago School extended to its view of the very purposes of antitrust. It argued that antitrust should be guided solely by economic efficiency.”

Central to the Chicago School is the assumption of rational behavior of all market participants. Their choices are rational, their behavior can be explained using rational reasoning, and their expectations are rational.

Stigler’s theory of Regulatory Capture asserts that, instead of serving the public’s interest, regulatory agencies in fact promote the interests of their respective regulated industries. The regulated industries achieve this by exerting political pressure that proves stronger than the dispersed political power of the public’s interest.

Another Chicago School scholar who had a significant influence on antitrust policy is Richard Posner. Posner argued that the 1960s antitrust laws actually pushed prices higher for consumers. Similar views were developed by Robert Bork, whose alma mater was the University of Chicago. In his 1978 book The Antitrust Paradox: A Policy at War with Itself (Basic Books, 1978), Bork argued that antitrust should focus on consumer welfare rather than competitors and that mergers often yielded beneficial results to consumers.

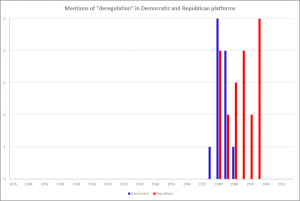

The ideas developed by the Chicago School, and specifically those of Stigler, Posner, and Bork, provided businesses with the intellectual authority needed to fight antitrust and regulation. They were adopted by both Republican and Democratic politicians, as well as their platforms, especially in the 1980 election cycle:

Republican platform, 1980 (Ronald Reagan v. Jimmy Carter):

“What ails American medicine is government meddling and the strait-jacket of federal programs. The prescription for good health care is deregulation and an emphasis upon consumer rights and patient choice.”

“Agencies should be made to justify every official form and filing requirement. Where possible, we favor deregulation, especially in the energy, transportation, and communications industries. We believe that the marketplace, rather than the bureaucrats, should regulate management decisions.”

Democratic platform, 1980 (Ronald Reagan v. Jimmy Carter):

“Regulatory Reform—Consistent with our basic health, safety, and environmental goals, we must continue to deregulate over-regulated industries and to remove other unnecessary regulatory burdens on state and local governments and on the private sector, particularly those which inhibit competition.”

“[under Regulatory Reform] For decades, the economy has been hamstrung by anticompetitive regulations. A Democratic Administration and a Democratic Congress are completing the most sweeping deregulation in history. Actions already taken and bills currently pending are revamping the rules governing airlines, banking, trucking, railroads, and telecommunications. Airline deregulation in its first year of operation alone has saved passengers over 2.5 billion dollars.”

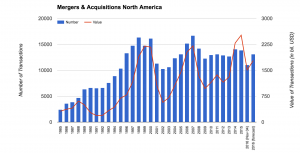

The Chicago School’s influence extended well into the 2000s, leading to a major wave of mergers and acquisitions. According to data gathered by the Institute for Mergers, Acquisitions and Alliances (IMAA), between 1985 and 1998, the number of mergers and acquisitions in North America grew almost 7-fold: from 2,385 to 16,330. The average for the years 1999-2015 is 13,330. The dollar value of the transactions fluctuates, but this is mainly attributable to booms and busts in overall stock prices.

The high levels of M&A activity coincided with a sharp rise in lobbying expenditure. According to the Center for Responsive Politics’ OpenSecrets.org, which provides data from 1998, total lobbying spending grew from $1.45 billion in 1998 to $3.22 billion in 2015.

Nevertheless, as Republican platforms continued to push for deregulation, Democratic platforms abandoned the subject completely after 1992.

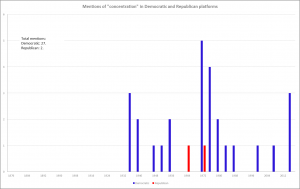

Analyzing the use of the term “concentration of economic power” and its derivatives sheds further light into how regulation and bigness became a partisan issue. The first mention was in the Democratic platform of 1936 (Alfred M. Landon v. Franklin D. Roosevelt) and the first mention in a Republican platform came in 1964 (Barry Goldwater v. Lyndon B. Johnson). While the term was used only twice by Republican platforms (once in 1964 and once in 1972), the mentions by Democratic platforms were much more extensive (27 times between 1936 and 2016). The Democratic spike came in 1972:

Democratic platform, 1972 (Richard Nixon v. George McGovern):

“[under Economic Management] To create new mechanisms to stop unwarranted price increases in concentrated industries.”

“The Democratic Party deplores the increasing concentration of economic power in fewer and fewer hands. Five per cent of the American people control 90 per cent of our productive national wealth. Less than one per cent of all manufacturers have 88 per cent of the profits. Less than two per cent of the population now owns approximately 80 per cent of the nation’s personally-held corporate stock, 90 per cent of the personally-held corporate bonds and nearly 100 per cent of the personally-held municipal bonds.”

“The Democratic Administration should pledge itself to combat factors which tend to concentrate wealth and stimulate higher prices.”

“[under Toward Economic Justice] Establish a temporary national economic commission to study federal chartering of large multi-national and international corporations, concentrated ownership and control in the nation’s economy.”

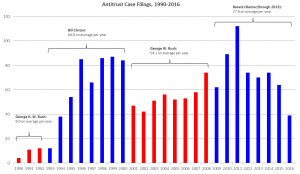

The degree to which it became a partisan issue can be anecdotally demonstrated by analyzing the number of antitrust cases filed by the Department of Justice, based on the DOJ’s data on such filings from 1990 to 2016.((See the DOJ’s antitrust case filing data here.)) Calculating the case file by each president reveals that filings made under Republican presidents were significantly smaller compared with Democratic presidents.

Although the Chicago School of thought is still powerful, a competing paradigm has been gaining recognition and traction, the main stream of which is behavioral economics. The scholars most identified with this school of thought are Daniel Kahneman, Vernon Smith, and Amos Tversky. In 2002, Kahneman and Smith won the Nobel Prize for their work.

Behavioral economists challenge the basic premise that humans act rationally. For example, one theory states that consumers discount the future more heavily than existing economic theory would predict and that, rather than making calculations, consumers are affected by their own past experiences and choices. This means that previous, more traditional, predictions related to consumer behavior–such as reacting to price changes–may be wrong and that the whole thinking behind markets, competitiveness, prices, efficiency–and therefore regulation, deregulation and antitrust–may be wrong as well.

Kahneman and Tversky started working on their theories over 35 years ago, but things may finally be starting to change.

On September 20th, in her first major address after becoming Acting Assistant Attorney General at the Antitrust Division, Renata Hesse laid her philosophy in front of the 2016 Global Antitrust Enforcement Symposium: “Antitrust,” Hesse said, “is making headlines again, and I don’t just mean in antitrust publications. It is, as it was at its inception, the stuff of popular imagination.((“And Never the Twain Shall Meet?” Acting Assistant Attorney General Renata Hesse of the Antitrust Division’s opening remarks at 2016 Global Antitrust Enforcement Symposium, September 2016.))

Republicans and Democrats in the House and Senate have been encouraging the federal agencies to be vigilant in their merger-enforcement and competition-advocacy roles. President Obama issued an executive order requiring agencies across the federal government to consider ‘specific actions’ to promote competition. And numerous op-eds and think-tank reports this year–from folks across the political and policy spectrums–have sounded the alarm on increasing concentration, have called for stepped up enforcement of the antitrust laws, and have implored federal and state agencies to tailor their regulations and policies so as to “promote competition by lowering barriers to entry and expansion.”

Hesse and others have been pointing to what seems like a pendular movement in antitrust, away from leniency and perhaps even negligence, toward new thinking and new policies for reinvigorating competitiveness and decreasing the concentration of economic power.

The impending US election sits at the end of a very long process of changes: academic, societal, business-related, and more recently, political.

As can probably be expected, the 2016 Republican platform still repeatedly and harshly criticizes regulation, including devoting a section to “Regulation: The Quiet Tyranny.” It also does not mention ideas related to concentration of power. However, it does include a section on “Crony Capitalism and Corporate Welfare,” although with a Republican flavor:

Republican platform, 2016 (Donald Trump v. Hillary Clinton):

“Cronyism is inherent in the progressive vision of the administrative state. When government uses taxpayer funding and resources to give special advantages to private companies, it distorts the free market and erodes public trust in our political system. By enlarging the scope of government and placing enormous power in the hands of bureaucrats, it multiplies opportunities for corruption and favoritism. It is the enemy of reform in education, the workplace, and healthcare. It gives us financial regulation that protects the large at the cost of the small.”

And it does find room for favoring regulation:

Republican platform, 2016 (Donald Trump v. Hillary Clinton):

“We endorse prudent regulation of the banking system to ensure that FDIC-regulated banks are properly capitalized and taxpayers are protected against bailouts.”

“Indeed, the world of the app economy cries out for the comprehensive regulatory reform proposed elsewhere in this platform. We must challenge established interests and traditional business patterns to facilitate market entry of new business models, including inventive means of transport, delivery, and communication.”

The winds of change are more apparent in the Democratic platform. For example, the addition of a section on “Promoting Competition by Stopping Corporate Concentration,” which addresses and binds together concentrated power, competition, and antitrust:

Democratic platform, 2016 (Donald Trump v. Hillary Clinton):

“Large corporations have concentrated their control over markets to a greater degree than Americans have seen in decades—further evidence that the deck is stacked for those at the top. Democrats will take steps to stop corporate concentration in any industry where it is unfairly limiting competition. We will make competition policy and antitrust stronger and more responsive to our economy today, enhance the antitrust enforcement arms of the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), and encourage other agencies to police anti-competitive practices in their areas of jurisdiction.

We support the historic purpose of the antitrust laws to protect competition and prevent excessively consolidated economic and political power, which can be corrosive to a healthy democracy. We support reinvigorating DOJ and FTC enforcement of antitrust laws to prevent abusive behavior by dominant companies, and protecting the public interest against abusive, discriminatory, and unfair methods of commerce. We support President Obama’s recent Executive Order, directing all agencies to identify specific actions they can take in their areas of jurisdiction to detect anticompetitive practices—such as tying arrangements, price fixing, and exclusionary conduct—and to refer practices that appear to violate federal antitrust law to the DOJ and FTC.”

It also addresses economic inequality:

Democratic platform, 2016 (Donald Trump v. Hillary Clinton):

“We believe that today’s extreme level of income and wealth inequality—where the majority of the economic gains go to the top one percent and the richest 20 people in our country own more wealth than the bottom 150 million—makes our economy weaker, our communities poorer, and our politics poisonous.”

And even targets Wall Street:

Democratic platform, 2016 (Donald Trump v. Hillary Clinton):

“[under Reining in Wall Street and Fixing our Financial System] To restore economic fairness, Democrats will fight against the greed and recklessness of Wall Street. Wall Street cannot be an island unto itself, gambling trillions in risky financial instruments and making huge profits, all the while thinking that taxpayers will be there to bail them out again. We must tackle dangerous risks in big banks and elsewhere in the financial system.”

Following Trump’s victory, it also remains to be seen how committed he will be to the party’s platform considering his anti-establishment spirit and his objection to the AT&T-Time Warner deal.

At any rate, there are more and more instances where Republicans promote regulation, either alone, or, more often, with Democratic lawmakers (see the discussion on the first installment of this series).

It is also becoming more evident that strict economic effectiveness may not be the only yardstick for deciding on and measuring policy; universal values such as fairness, equity, and long-term stability should be taken into account. In fact, Hesse went as far as to say in her address that “antitrust is too important to be left solely in the hands of antitrust experts.”

The Sherman Act of 1890 and the laws that followed it gave the US and the developed world a tool for dealing with the huge businesses that were the result of the Industrial Revolution. Since then, not only did technologies and business practices change, but also new paradigms, based on experience, data, and learning, evolved.

The “spring” of U.S. antitrust, the period in which Thurman Arnold oversaw the Antitrust Division, ended 73 years ago. Now may be the time for spring again. The most powerful agent of change, the political system, seems to be ready. The discourse is changing, the right and the left are converging, and more empirical data is accumulating.