In the third installment of our four-part series on the history of antitrust language in American political discourse, we review the evolution of economic language related to trusts and antitrust in all Democratic and Republican platforms from 1876 to the end of WWII.

This is the third installment in our series, “140 Years of Antitrust: Are Brandeisian Pro-Competition and Anti-Monopoly Sentiments Coming Back into the Political Discourse?” The first installment can be found here and the second installment can be found here.

While both Democrats and Republicans appear eager to jump on any opportunity to take opposite sides on issues in order to win over voters, AT&T’s move to buy Time Warner for around $85 billion seems to have achieved the a different response.

On Saturday, the day the proposed deal was formally announced, Republican nominee Donald Trump was very clear on where he stood on this issue: “As an example of the power structure I’m fighting, AT&T is buying Time Warner and thus CNN, a deal we will not approve in my administration because it’s too much concentration of power in the hands of too few.”

Hillary Clinton has not yet expressed her view publicly, but her running mate Tim Kaine said on Meet the Press on Sunday that “pro-competition and less concentration, I think, is generally helpful, especially in the media.” Separately, her campaign’s spokesperson Brian Fallon said on Sunday: “We think that marketplace competition is a good and healthy thing for consumers and so there’s a number of questions and concerns that arise in that vein about this announced deal.”

Bernie Sanders was at least as decisive as Trump, as he tweeted late on Sunday that “The administration should kill the Time Warner-AT&T merger. This deal would mean higher prices and fewer choices for the American people.”

And at least one statement related to the brewing deal was made jointly by a Republican Senator and a Democratic Senator, Mike Lee (R-UT) and Amy Klobuchar (D-MN), of the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust, Competition Policy, and Consumer Rights: “An acquisition of Time Warner by AT&T,” the two wrote on Sunday, “would potentially raise significant antitrust issues, which the subcommittee would carefully examine.”

In fact, the apparent opposition to the deal is so overwhelming that on Monday Reuters reported that both companies’ shares slid “amid concerns over deal clearance.”((Jessica Toonkel and Supantha Mukherjee, “Time Warner, AT&T shares fall with concerns over deal clearance.” Reuters, October 2016.))

Donald Trump’s attack on the AT&T-Time Warner deal is the first time in this race that Republicans used strong language related to antitrust, bigness and concentration of power. Most of the language so far has come from the Democratic Platform, Hillary Clinton, and Senator Elizabeth Warren.

But this was not always the case.

The fight against trusts and big business was invented and pursued by Republicans: Republican John Sherman provided the legislative groundwork in 1890 and Republican presidents Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909) and William Howard Taft (1909-1913) followed that legislation with 12 years in which tens of antitrust suits were filed.

Nevertheless, the biggest concentration of antitrust cases occurred during a five-year period, 1938-1943, under FDR’s presidency. By then, trusts were all but gone and fighting trusts had become more identified with Democrats.

Origins

The derogatory term for big business magnates, “robber barons,” appeared in 1882, the same year that the first trust was created. Eight years later, the first–and still most useful–antitrust law, the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act, was enacted.

According to Google’s Ngram Viewer, which charts the frequency of words found in printed sources between 1800 and 2000, the term “robber baron” started appearing in the mid-1880s:

It is worth noting that the surge in the literary use of “robber barons” began around 1950–long after most trusts had been dissolved.

John Tipple’s 1959 article, “The Anatomy of Prejudice: Origins of the Robber Baron Legend,”((John Tipple, “The Anatomy of Prejudice: Origins of the Robber Baron Legend,” The Business History Review No. 4 (1959): 510-523.)) provides not only a definition, but also a more precise time frame: “The Robber Baron Legend,” he writes, “is an outgrowth of the hostile criticism which was directed against the big businessman in the latter part on the nineteenth century. The phrase is believed to have been coined by Carl Schurz in 1882 and was used in his Phi Beta Kapa Oration at Harvard University to describe certain big businessmen whose highly individualistic practices seemed to him suggestive of the war-like pillagings of the feudal nobility of the Middle Ages.”

All this suggests that by the mid-1880s, the phenomenon of businesspeople who controlled whole industries enough to set prices was so prevalent that it justified a term that is still repeated. The fact that it was unflattering also points to the feelings ordinary citizens, academics, politicians, and at least certain members of the press had for these businesspeople and their influence.

A term closely associated with “robber barons” is “trusts,” the legal construct by which these businesspeople arranged their holdings. The first such trust is believed to have been created in 1882 by John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil as an agreement in which owners of oil producing companies transferred their ownership rights to an entity called a trust.((Barak Orbach and Grace E. Campbell Rebling, “The Antitrust Curse of Bigness,” Southern California Law Review 605 (2012).)) This mechanism was then used by many other businesspeople in a number of industries.

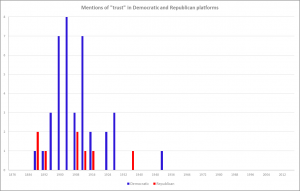

“Trust” first appeared in both the Republican and Democratic platforms of 1888, six years after the first trust was created and two years before the Sherman act:

Democratic platform, 1888 (Benjamin Harrison v. Grover Cleveland):

“Judged by Democratic principles, the interests of the people are betrayed, when, by unnecessary taxation, trusts and combinations are permitted and fostered, which, while unduly enriching the few that combine, rob the body of our citizens by depriving them of the benefits of natural competition.”

Republican platform, 1888 (Benjamin Harrison v. Grover Cleveland):

“We declare our opposition to all combinations of capital organized in trusts or otherwise to control arbitrarily the condition of trade among our citizens; and we recommend to Congress and the State Legislatures in their respective jurisdictions such legislation as will prevent the execution of all schemes to oppress the people by undue charges on their supplies, or by unjust rates for the transportation of their products to market.”

The Sherman Act

The Sherman Act was a watershed in U.S. regulation. John Sherman (1823-1900), who started his career as a lawyer, was originally a member of the Whig Party but then joined an anti-slavery group that later became the Republican Party. He began his political career as a representative of his home state of Ohio’s 13th District, and later became Secretary of the Treasury, a U.S. Senator, and then Secretary of State.

Sherman, who was very active in financial issues, was involved in many laws that laid the foundation for the post-Civil-War era and beyond, including the Coinage Act of 1873, which set the Gold Standard; the 1878 Bland-Allison Act, which created the silver dollars; the 1883 “Mongrel” Tariff Act, which helped prolong protectionist barriers; and the 1890 Sherman Silver Purchase Act. But he is best known for the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act.

Both Democratic and Republican leaders were concerned with the growing numbers and influence of trusts and their adverse effect on prices. The best-known robber barons of their day were John D. Rockefeller, John Pierpont “J.P.” Morgan (banking), Andrew Carnegie (steel), and Charles Crocker (railroads).

Until the 51st Congress, which opened in March 1889, Sherman, then a senator, had little interest in trusts. But then he took a failed bill from the preceding Congress, amended it and re-introduced it as the Sherman Antitrust Act.

The first section of the Act was very clear:

“Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is declared to be illegal.”

The Senate voted overwhelmingly in favor of the Act and it passed the House without dissent. In the first election after the law was enacted, 1892, both parties’ platforms mentioned trusts:

Democratic platform, 1892 (Benjamin Harrison v. Grover Cleveland):

“We recognize in the Trusts and Combinations, which are designed to enable capital to secure more than its just share of the joint product of Capital and Labor, a natural consequence of the prohibitive taxes, which prevent the free competition, which is the life of honest trade, but believe their worst evils can be abated by law, and we demand the rigid enforcement of the laws made to prevent and control them, together with such further legislation in restraint of their abuses as experience may show to be necessary.”

Republican platform, 1892 (Benjamin Harrison v. Grover Cleveland):

“We reaffirm our opposition, declared in the Republican platform of 1888, to all combinations of capital organized in trusts or otherwise, to control arbitrarily the condition of trade among our citizens.”

From 1892 to 1908, three consecutive election cycles, the Republican platforms made no mention of the term. On the other hand, Democratic platforms increased their mentions, using it also as a tool to criticize Republicans:

Democratic platform, 1900 (William McKinley v. William Jennings Bryan):

“They are the most efficient means yet devised for appropriating the fruits of industry to the benefit of the few at the expense of the many, and unless their insatiate greed is checked, all wealth will be aggregated in a few hands and the Republic destroyed. The dishonest paltering with the trust evil by the Republican party in State and national platforms is conclusive proof of the truth of the charge that trusts are the legitimate product of Republican policies, that they are fostered by Republican laws, and that they are protected by the Republican administration, in return for campaign subscriptions and political support.

We pledge the Democratic party to an unceasing warfare in nation, State and city against private monopoly in every form. Existing laws against trusts must be enforced and more stringent ones must be enacted providing for publicity as to the affairs of corporations engaged in inter-State commerce requiring all corporations to show, before doing business outside the State of their origin, that they have no water in their stock, and that they have not attempted, and are not attempting, to monopolize any branch of business or the production of any articles of merchandise; and the whole constitutional power of Congress over inter-State commerce, the mails and all modes of inter-State communication, shall be exercised by the enactment of comprehensive laws upon the subject of trusts. Tariff laws should be amended by putting the products of trusts upon the free list, to prevent monopoly under the plea of protection. The failure of the present Republican administration, with an absolute control over all the branches of the national government, to enact any legislation designed to prevent or even curtail the absorbing power of trusts and illegal combinations, or to enforce the anti-trust laws already on the statute-books proves that insincerity of the high-sounding phrases of the Republican platform.”

Democratic platform, 1904 (Alton B. Parker v. Theodore Roosevelt):

“We recognize that the gigantic trusts and combinations designed to enable capital to secure more than its just share of the joint product of capital and labor, and which have been fostered and promoted under Republican rule, are a menace to beneficial competition and an obstacle to permanent business prosperity.”

“Individual equality of opportunity and free competition are essential to a healthy and permanent commercial prosperity; and any trust, combination or monopoly tending to destroy these by controlling production, restricting competition or fixing prices and wages, should be prohibited and punished by law.”

“We demand a strict enforcement of existing civil and criminal statutes against all such trusts, combinations and monopolies; and we demand the enactment of such further legislation as may be necessary effectually to suppress them.”

“Any trust or unlawful combination engaged in inter-State commerce which is monopolizing any branch of business or production, should not be permitted to transact business outside of the State of its origin, whenever it shall be established in any court of competent jurisdiction that such monopolization exists.”

The federal government started suing companies under the law as early as 1890, but perhaps the most notable court case was Northern Securities Co. v. United States. The case involved a battle between James Jerome Hill and J.P. Morgan on one side and Edward Henry Harriman on the other side over the U.S. railroad market. Northern Securities was the company created by Hill to counter Harriman. Eventually, on March 1904, the Supreme Court decided to dissolve the Northern Securities Company.

Another major case was Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States, in which the Supreme Court decided, on May 1911, to break Standard Oil into separate entities that eventually competed against each other.

The law was even applied over a century after it was passed, in 2001’s United States v. Microsoft Corp. In this case, however, Microsoft was not broken up.

The Sherman Act marked the beginning of a new era, in which the federal government was starting to become more involved in the economy. It also marked the beginning of a very influential political movement, Progressivism, which spanned the presidencies of Teddy Roosevelt (1901-1909), William Howard Taft (1909-1913), and Woodrow Wilson (1913-1921).

The Northern Securities Co. v. United States case was the biggest achievement of the trust-busting president–Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919).

Between 1901, when Roosevelt first became president, and 1921, the end of Wilson’s presidency, federal policies were mainly focused on social issues and fighting corruption.

This era also saw the creation and proliferation of a new brand of journalism: muckraking. Muckrakers focused on exposing corruption in business and government and on exploitation of workers. They were agenda-driven and used their writing to push for reform.

The most notable muckraking publication was McClure’s, a monthly magazine that operated between 1893 and 1929. One major story run by McClure’s was Ida Tarbell’s 1902 series on Rockefeller’s Standard oil. Tarbell also published a book on the issue in 1904, The History of the Standard Oil Company, which became a bestseller.((Felicity Barringer, “Journalism’s Greatest Hits: Two Lists of a Century’s Top Stories.” New York Times, March 1999.))

Progressive ideas, Roosevelt’s leadership, and muckraking journalism created an ecosystem that allowed all to prosper.

On December 3, 1901 Roosevelt delivered a 20,000-word speech in Congress in which he laid out his convictions, including on trusts:((Theodore Roosevelt: “First Annual Message,” December 3, 1901. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project.))

“The large corporations, commonly called trusts, though organized in one State, always do business in many States, often doing very little business in the State where they are incorporated. There is utter lack of uniformity in the State laws about them; and as no State has any exclusive interest in or power over their acts, it has in practice proved impossible to get adequate regulation through State action. Therefore, in the interest of the whole people, the Nation should, without interfering with the power of the States in the matter itself, also assume power of supervision and regulation over all corporations doing an interstate business. This is especially true where the corporation derives a portion of its wealth from the existence of some monopolistic element or tendency in its business. There would be no hardship in such supervision; banks are subject to it, and in their case it is now accepted as a simple matter of course. Indeed, it is probable that supervision of corporations by the National Government need not go so far as is now the case with the supervision exercised over them by so conservative a State as Massachusetts, in order to produce excellent results.”

Roosevelt also helped workers fight against a large trust. In 1902 the United Mine Workers of America went on strike demanding better wages, shorter working hours, and recognition of their union. A key figure in this standoff was J.P. Morgan, whose railroad company was one of the biggest employers of miners (and a member of the losing party in the Northern Securities Co. v. United States case). Following Roosevelt’s intervention, the strikers did not get the recognition they wanted, but they did get a 10 percent raise and shorter workdays.

J.P. Morgan and Roosevelt found themselves on opposing sides again in 1906, during Roosevelt’s second term, when the Hepburn Act, which gave the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) the power to set maximum railroad rates, was enacted.

Taft was committed to fighting trusts and to the Sherman Act. In fact, during his four years in office, his administration launched 80 antitrust suits, more than Roosevelt had launched in his seven and a-half years in office.

The Democratic platform of 1912, the year Wilson won his first term, again included trusts as a major issue:

Democratic platform, 1912 (William Howard Taft v. Woodrow Wilson):

[on Anti-Trust Law:] “A private monopoly is indefensible and intolerable. We therefore favor the vigorous enforcement of the criminal as well as the civil law against trusts and trust officials, and demand the enactment of such additional legislation as may be necessary to make it impossible for a private monopoly to exist in the United States.”

“We condemn the action of the Republican administration in compromising with the Standard Oil Company and the tobacco trust and its failure to invoke the criminal provisions of the anti-trust law against the officers of those corporations after the court had declared that from the undisputed facts in the record they had violated the criminal provisions of the law.”

But nevertheless, Wilson adopted a different approach toward regulation: instead of turning to courts to fight trusts, he created the 1914 Federal Trade Commission Act, which was tasked with preventing unfair methods of competition and unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce.

Wilson also signed the 1914 Clayton Antitrust Act into law. The Act was meant to add to the Sherman Act by not only declaring that trusts and monopolies are unlawful but also prohibiting their creation. But bad wording rendered it almost toothless and actually encouraged a huge wave of mergers, a combination mechanism that it did not address.

The case of Robert La Follette is another example of how fighting trusts was a powerful enough motivator to bring together leaders from opposing sides. La Follette, a lawyer, was originally a Republican who served as a member of the House of Representatives, a Senator, and as the Governor of Wisconsin.

In his description of La Follette, David Myers wrote:((R . David Myers, “David La Follette,” in The American Radical, eds. Mari Jo Buhle, Paul Buhle, and Harvey J. Kaye (New York: Routledge,1994), 159.))

“A constant struggle for post-Civil War American radicals was the quest to overcome the inequities caused by the growth of large-scale corporate capitalism. For several decades, Robert M. La Follette was arguably the most important and recognized leader of the opposition to the growing dominance of corporations over the government of the United States… La Follette waged a constant battle against corporate domination.”

During the early 1890s, La Follette concluded that his party was becoming a tool for corporate interests, which in his home state of Wisconsin were the railroad and timber industries. This led him to create an independent organization within the Republican Party, “The Insurgents.”

After years of fighting the leaders of the Republican Party, in 1924 La Follette founded the Progressive Party and was nominated as its presidential candidate. His platform echoed his ideas:

Progressive party platform, 1924 (Calvin Coolidge v. John W. Davis v. Robert La Follette):

“Almost unlimited prosperity for the great corporations and ruin and bankruptcy for agriculture is the direct and logical result of the policies and legislation which deflated the farmer while extending almost unlimited credit to the great corporations; which protected with exorbitant tariffs the industrial magnates, but depressed the prices of the farmers’ products by financial juggling while greatly increasing the cost of what he must buy; which guaranteed excessive freight rates to the railroads and put a premium on wasteful management while saddling an unwarranted burden on to the backs of the American farmer; which permitted gambling in the products of the farm by grain speculators to the great detriment of the farmer and to the great profit of the grain gambler.”

La Follette only received 13 of 531 electoral votes.

While Roosevelt provided the national leadership and Sherman and Clayton provided the legislative push, Louis Brandeis (1865-1941) provided the legal bedrock on which all their actions were based.

Brandeis was a progressive, but he never entered politics. He was a lawyer and a judge throughout his career. He entered Harvard Law School at the age of 18 and graduated with high grades. After a few months in a Kentucky law firm, he went back to Boston and co-founded a law firm, which is still active under the name Nutter McClennen & Fish.

Brandeis had strong social convictions, which he incorporated into his work and writings. In 1905, at age 40, Brandeis picked a legal fight against J.P. Morgan: he waged a successful 7-year legal battle against J.P. Morgan’s plan to merge his existing railroad companies with Boston & Maine Railroad.

In 1914 Brandeis published his book, Other People’s Money and How the Bankers Use It,((Louis Dembitz Brandeis. Other People’s Money, And How the Bankers Use It. Washington: National Home Library Foundation (1933).)) which was very influential. In it, he criticized investment banks, arguing that they used deposits to support the other, non-financial, businesses they were involved in. He was also against the consolidation of businesses which were controlled by few people. The goal of such entities, he argued, was to stifle competition and innovation.

In a 2009 opinion piece in The New York Times, Melvin Urofsky, a professor at Virginia Commonwealth University and the author of Louis D. Brandeis: A Life, described the influence that Brandeis’ book had over the public and lawmakers:((Melvin I. Urofsky, “The Value of ‘Other People’s Money.’” New York Times, 2009.))

“During the Great Depression, people turned to Brandeis once again. ‘Other People’s Money’ was reissued in an inexpensive edition, and many of those who came to Washington to work on Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal read it. The New Deal laws, particularly the Glass-Steagall and the Securities Exchange Acts, imposed long overdue regulation of the banking system, required the separation of banking from stock brokerage, and established the Securities and Exchange Commission to regulate the stock markets.”

In 1916, two years after Brandeis’ book was published, President Wilson decided to nominate Brandeis to the Supreme Court. The nomination did not go unchallenged, but eventually, four months after Wilson’s nomination, Brandeis was confirmed as Associate Justice and started serving on June 1, 1916. During his tenure, which lasted until February 13, 1939, his most notable cases mainly involved two of his areas of expertise: freedom of speech and the right to privacy.

The 31-year period between 1890, when the Sherman Act was enacted, and the end of Wilson’s presidency in 1921 was indeed characterized by fights against trusts, mainly using the Sherman Act. And indeed, many suits were filed and many trusts were broken up.

But the golden age of trust busting was still ahead.

When FDR started his first term in 1933, the U.S. was struggling with the Great Depression. The 1932 Democratic platform was still committed to fighting trusts:

Democratic Party platform, 1932 (Herbert Hoover v. Franklin D. Roosevelt):

“We advocate strengthening and impartial enforcement of the anti-trust laws, to prevent monopoly and unfair trade practices, and revision thereof for the better protection of labor and the small producer and distributor.”

But it would be some years before FDR pursued this goal. Upon his election, FDR announced his first New Deal. One major piece of the New Deal was the 1933 National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), which could be interpreted as not being in line with competition, as it was intended to, among other things, raise prices. Eventually, as it was so broad-reaching, it was declared unconstitutional and therefore nullified by the Supreme Court in 1935.

Following the Supreme Court defeat, FDR initiated his second New Deal, which lasted until 1938. It was during these years that the economy started to recover: (1) the unemployment rate fell from an estimated 25 percent in 1933 to 15 percent in 1937, (2) real GDP in the period between 1933 and 1937 grew 43 percent, (3) and prices rose.

Accordingly, the 1936 Democratic platform was more confident on antitrust issues:

Democratic platform, 1936 (Alfred M. Landon v. Franklin D. Roosevelt):

[on Monopoly and Concentration of Economic Power:] “Monopolies and the concentration of economic power, the creation of Republican rule and privilege, continue to be the master of the producer, the exploiter of the consumer, and the enemy of the independent operator. This is a problem challenging the unceasing effort of untrammeled public officials in every branch of the Government. We pledge vigorously and fearlessly to enforce the criminal and civil provisions of the existing anti-trust laws, and to the extent that their effectiveness has been weakened by new corporate devices or judicial construction, we propose by law to restore their efficacy in stamping out monopolistic practices and the concentration of economic power.”

Following the enactment of the Sherman Act, antitrust cases were handled by the Attorney General. In 1903, during Theodore Roosevelt’s presidency, antitrust laws were enforced by the Assistant to the Attorney General. It was only in 1933, at the beginning of FDR’s first term, that the Antitrust Division was created within the Department of Justice.

In March of 1938, FDR nominated Thurman Arnold to head the division. In the five years that passed before Arnold left office in 1943, the division filed 44 percent of the suits that were filed in the first 53 years after the Sherman Act became law.

The case that Arnold is best known for was set into motion immediately after he assumed office: attacking one of the nation’s biggest and most influential trade groups–the American Medical Association (AMA).

The AMA tried to prohibit its members from working for the Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs), which emerged during the Great Depression. Specifically, Arnold focused on the District of Columbia. He even used FBI agents to gather evidence.((Spencer Weber Waller, “The Antitrust Legacy of Thurman Arnold,” 78 St. John’s Law Review 569 (2004).)) The case ended with convictions and fines: $2,500 for the AMA and $1,500 for the District of Columbia Medical Society. The defendants appealed, but in 1943 the Supreme Court upheld the convictions by a vote of six to zero.

Two of Arnold’s other major cases were United States v. South-Eastern Underwriters Association, where the Supreme Court ruled that the Sherman Act could be applied to insurance companies, and United States v. Socony-Vacuum Oil Co. when the Supreme Court held that price-fixing is illegal per se.

Once the US entered WWII, the public, as well as FDR, were more focused on mobilizing the American economy to help with the war effort than on fixing its competitive structure.