While the World Bank scrambles to contain the Doing Business rankings firestorm, a new paper by Rabia Malik and Randall Stone traces a more insidious source of partiality in how the Bank does development work.

World Bank chief economist Paul Romer prompted widespread dismay when he admitted last week that the Bank’s Doing Business rankings may have been manipulated to make Chile’s economic environment look worse under the sitting socialist president Michelle Bachelet. The scandal now threatens not just Romer’s position at the Bank but also that Bretton Woods institution’s overall sheen as one of the better-behaved organs of international governance.

The World Bank has long prided itself on keeping its nose clean, with Stephen Zimmermann, the operations director of its Integrity Vice Presidency, last year touting the Bank as “a leader in setting a high bar for integrity standards and in international development financing.” A handful of internal “integrity offices” like Zimmermann’s own were set up in most UN agencies and international financial institutions (IFIs) in the aftermath of the corruption-riddled oil-for-food program, a UN humanitarian initiative in Iraq that Saddam Hussein hijacked for his own enrichment in an imbroglio that one US senator called “the biggest financial scandal ever” and that, according to The Economist, “threatened to discredit the whole United Nations system.”

Some 15 years have passed since the winding down of oil-for-food—years that until the current Chile debacle have been largely free of any equivalently spectacular displays of corruption in international organizations. Scholars and activists, in the meantime, have homed in on other potential sources of partiality that could jeopardize IFIs’ independence in fulfilling their mission to promote development and fight poverty. Study after study has investigated whether powerful donor countries try to influence IFIs’ development projects to further their own geopolitical or ideological agendas (see, e.g., Thacker 1999, Fleck and Kilby 2005, Kilby 2013).

One key lever that researchers have looked at (and dozens of NGOs have decried) is conditionality in development lending: that is, withholding of development funds when states don’t meet the conditions, usually requirements to undertake political or economic reforms, attached to their development loans. Variously lambasted as a vehicle for imposing the Washington consensus in inappropriate contexts or a mostly unenforced measure deployed to punish countries that don’t politically align with the United States, conditionality is generally agreed to not be working quite how it should be. Why it’s not working remains a matter of some debate, though.

One surprising new answer to that question traces a source of conditionality dysfunction not to the country but to the multinational firm level. A brand-new Journal of Politics paper finds that, rather than by member states’ geopoliticking, the World Bank’s conditionality system—and with it, the Bank’s independence—has been compromised by collusion between multinational firms in the United States and Japan with Bank project authorities.

Allies in Sustainable Development?

What’s novel about all this is not just that the paper by Rabia Malik of NYU Abu Dhabi and Randall Stone of the University of Rochester is one of the first to track bias in international development lending back to politicking by individual firms instead of national governments. It’s that their findings specifically contradict the rosy portrait painted of multinationals by standard FDI models as accomplices to development. Investing in foreign projects can often be more attractive to top firms than exporting to foreign consumers, this line of thinking goes, and such firms usually bring technology and know-how that should make them key allies in development projects.

Not exactly, say Malik and Stone. They code a newly released set of Bank project reports and combine them with firm-level data on participation and investment in Bank projects. The initial correlations they find are worrisome: when Fortune 500 multinationals participate as contractors or invest in countries with World Bank projects, those projects do not perform better but are nonetheless more likely to receive unjustified loan disbursements as well as get inflated evaluations from Bank staff.

The seed of the problem, the authors say, lies in the obvious disconnect between the World Bank’s various sustainable development goals and MNCs’ single-minded focus on their bottom lines. Unlike critics who question the legitimacy of conditionality in itself, Malik and Stone from the outset assume that maintaining the Bank’s reputation for withholding loan disbursements when conditions are unmet is desirable in that it allows the Bank to enforce compliance with its various environmental, human rights, and development mandates. Firms that participate in projects, however, are only interested in seeing specific projects succeed and thus they lobby for withheld funds to be released. World Bank staff, in turn, have incentives to make projects look better to boost their own career prospects and so are more likely to be pliant in the face of corporate pressure. The perverse incentives all this creates for both MNCs and Bank staff, Malik and Stone argue, are part of what has jeopardized the integrity of the Bank’s lending process.

All that being said, “collusion” is a strong word, and Malik and Stone’s initial regression analysis only manages to show that, in 4,206 World Bank projects carried out between October 1994 and September 2013, the presence of an MNC as a contractor shows a significant relationship with unjustified loan disbursements and inflated evaluations. They estimate the marginal effect of having an MNC contractor as a small but significant 2.7 percent increase in disbursement rates.

Tightening Down on the Chain of Influence

To bolster their case that MNCs are in fact doing something to cause the unjustified extra disbursements, the researchers add several extra stages to their analysis where they clamp down on the hypothesized channel of influence to see if the association gets stronger. First, they break down the MNCs involved in Bank projects by the countries they’re headquartered in, on the hunch that if political influence is at work in some form, companies from countries with greater voting power at the Bank (see Figure 1) should have a stronger effect on loan disbursements. As they expect, the presence of firms from the United States and Japan is associated with more disbursements.

Next, they zero on in firms likely to have incentives to see a project carried through to completion. When they test the correlation of management contractors with increased loan disbursements, the marginal effect of the presence of the contractor jumps to 7.2 percent, largely driven by the particular oomph of US contractors, who deliver a 10.1 percent boost to disbursement rates.

Malik and Stone squeeze down further on the hypothesized channel of influence by regressing the presence of management MNCs against their measure of inflated project evaluations. The presence of MNCs overall increases evaluation inflation, but when the results are broken down by country it’s clear that effect is driven by the significant influence of US and Japanese firms. “The results,” say Malik and Stone, “are consistent with our interpretation … that multinationals collude with Bank staff to frustrate project monitoring”—although that collusion appears to be effective only for companies headquartered in the Bank’s two biggest donor countries.

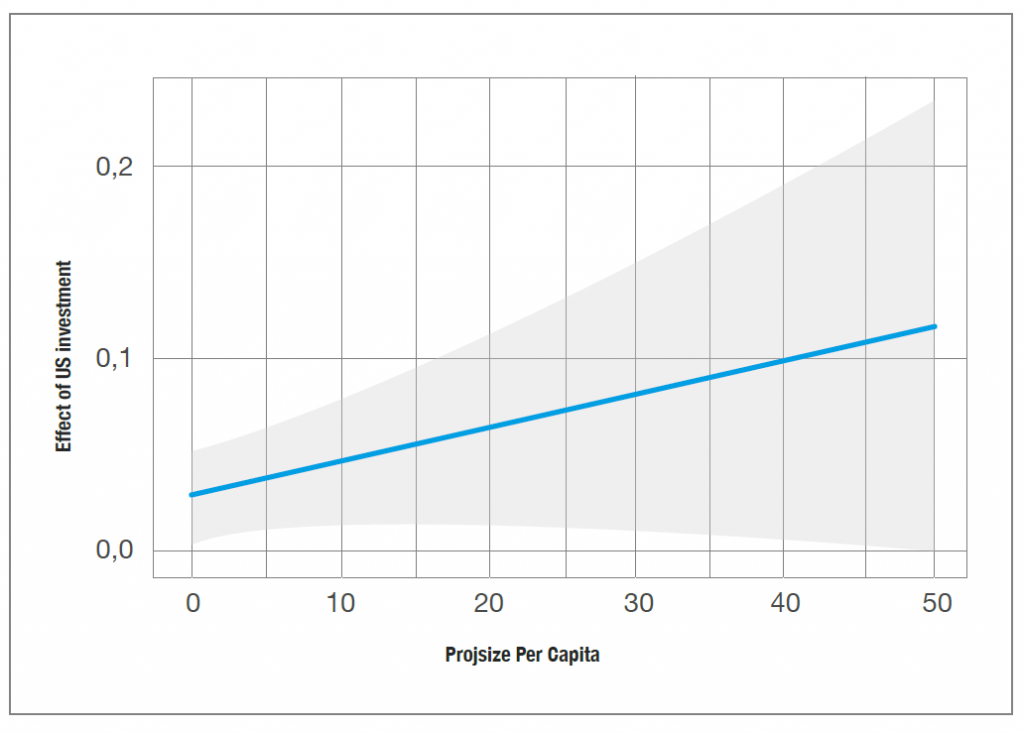

If the involvement of American and Japanese firms as contractors is clearly affecting Bank decisions to release fund projects on projects that they’d otherwise be withholding, then the natural follow-up question is: do these firms also affect Bank disbursements when they have an outside stake in project success? To check the robustness and scope of their initial findings, Malik and Stone move on test whether investment by Fortune 500 firms in countries with World Bank projects (interacted with a measure of project size per capita, on the hunch that bigger projects are likely to be of more interest to multinationals) are also correlated with unjustified disbursements. And yes—they still find the effect they’re looking for. (See Figure 2 below for a look at US firms specifically with reference to project size.)

So how exactly do the worrisome dynamics that Malik and Stone are capturing on a large-scale play out in the real world? They delve into one example drawn from their dataset, the Yacyretá Hydroelectric Project II carried out in Argentina from 1992 to 2000, plagued by human rights and ecological problems from the outset and called a “monument to corruption” by then Argentine president Carlos Menem in the wake of the conviction of members of the project’s administrative body for embezzlement and insider trading and charges of human rights violations by the IACHR.

The Yacyretá project garnered an “unsatisfactory” evaluation from the Bank, but still received 100 percent of loan disbursements. That dam was planned, designed, and built by the US Fortune 500 company MWH Global, which also served as general contractor on 13 other Bank projects from the year 2000 on (see Table 1 below). Eleven of those projects received full disbursements or even expansions (the average disbursement came out to 102 percent of the committed funds, bringing in a total of $31 million to MWH) despite earning moderately unsatisfactory project evaluations. In the meantime, US lobbying disclosures reveal that MWH spent $170,000 within two years alone as a client of the lobbying firm Livingston Group, run by former House Appropriations chairman Robert Livingston.

Is Something Else at Work?

Finally, Malik and Stone entertain a couple of alternative explanations for the dynamics they document. One possibility is that a favorable institutional climate in project locations makes it more likely that the projects will turn out better and receive full disbursements. In this case aggregate FDI flows and stocks at the country level should also correlate with disbursements—and they do not. Nor does adding controls for FDI flows and stocks to the regressions where MNC involvement is the independent variable change the results. Clearly the presence of MNCs themselves is key to the Bank’s ineffective use of loan conditionality.

Another possibility—one surmised to be at work as far back as the 1970s (see Gilpin 1975)—is that multinationals simply serve as proxies that carry out the United States’ geopolitical agenda in countries with Bank projects. In other words, MNCs could be operating at the behest of the US government, rather than the other way around. The researchers put together a composite variable of geopolitical interest that includes factors drawn from the literature that have been found to affect IFI lending—things like whether the recipient country sat on the UN Security Council or the Bank’s Executive Board, amount of US aid, and how often the receiving country votes with the United States at the UN. Only one of the coefficients seems to play a role in loan disbursement (the UN vote alignment) but does not affect inflation of project evaluations.

Market Power Goes Global

Geopolitics overall, then, appears not to be driving the conditionality dynamics that Malik and Stone have uncovered. “Rather, it represents the effects of political activity that the firms pursue on their own behalf,” the authors write:

The results support the interpretation that major MNCs collude with governments in the developing world to circumvent the monitoring of World Bank project performance and lobby on behalf of loan disbursements that are unjustifiable in terms of the achievement of project objectives.

Corrupt states skimming money off the top of development funds or technocrats allegedly manipulating statistics for ideological ends may be flagrant examples of how political capture of IFIs may occur. But Malik and Stone’s research warns of how more insidious mechanisms might be jeopardizing the independence of development agencies. As large firms in rich countries use their market power to tighten their grip on political power, their influence is now rippling out to compromise the credibility of international institutions.

In short, when it comes to multinationals allying with the World Bank to carry out sustainable development projects, the tail now appears to be wagging the dog.

Disclaimer: The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.