The Industrial Funding Fee pays $3 million a year for a 23-year old McKinsey employee instead of hiring an experienced person directly to do IT management. The government agency in charge of bulk buying isn’t paid for saving money, but for spending too much of it.

A few weeks ago, Ian MacDougall came out with a New York Times/ProPublica piece on how consulting giant McKinsey structured Trump immigration policy. Lots of people cover immigration. I’m going to discuss why the government buys overpriced services from McKinsey. (Spoiler: It goes back to, of course, Bill Clinton.)

McKinsey has a lot of high-flying rhetoric about strategy, sustainability, and social justice. The company ostensibly pursues intellectual and business excellence, while also using its people skills to help Syrian refugees. That’s nice.

But let’s start with what McKinsey is really about, which is getting organizational leaders to pay a large amount of money for fairly pedestrian advice. In MacDougall’s article on McKinsey’s work on immigration, most of the conversation has been about McKinsey’s push to engage in cruel behavior towards detainees. But let’s not lose sight of the incentive driving the relationship, which was McKinsey’s political ability to extract cash from the government. Here’s the nub of that part of the story:

“The consulting firm’s sway at ICE grew to the point that McKinsey’s staff even ghostwrote a government contracting document that defined the consulting team’s own responsibilities and justified the firm’s retention, a contract extension worth $2.2 million. “Can they do that?” an ICE official wrote to a contracting officer in May 2017.

The response reflects how deeply ICE had come to rely on McKinsey’s assistance. “Well it obviously isn’t ideal to have a contractor tell us what we want to ask them to do,” the contracting officer replied. But unless someone from the government could articulate the agency’s objectives, the officer added, “what other option is there?” ICE extended the contract.”

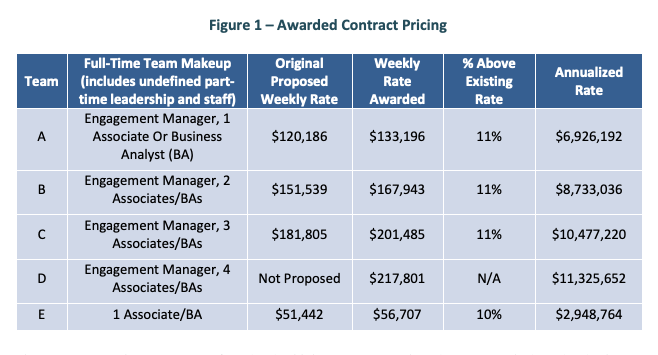

Such practices used to be called “honest graft.” And let’s be clear, McKinsey’s services are very expensive. Back in August, I noted that McKinsey’s competitor, the Boston Consulting Group, charges the government $33,063.75/week for the time of a recent college grad to work as a contractor. Not to be outdone, McKinsey’s pricing is much much higher, with one McKinsey “business analyst”—someone with an undergraduate degree and no experience—lent to the government priced out at $56,707/week, or $2,948,764/year.

How does McKinsey do it? There are two answers. The first is simple. They cheat. McKinsey is far more expensive than its competition and is able to get that pricing because of its unethical tactics. In fact, the situation is so dire that earlier this year, the General Services Administration’s Inspector General recommended in a report that the GSA cancel McKinsey’s entire government-wide contract. Here’s what the IG showed McKinsey was eventually awarded:

The Inspector General illustrated straightforward corruption at the GSA, which is the agency that sets schedules for how much things cost for the entire US government (and many states and localities who also use GSA schedules).

What happened is fairly simple. McKinsey asked for a 10-14 percent price hike for its already expensive IT professional services (which is a catch-all for anything). The government contracting officer said no, calling the proposal to update the firm’s contract schedule with much higher costs “ridiculous.” So McKinsey went to the officer’s boss, the Division Director. In 2016, a McKinsey representative sent the following email to the GSA Division Director:

“We would really appreciate it if you could assist us with our Schedule 70 application. In particular, given that you understand our model, it would be enormously helpful if you could help the Schedule 70 Contracting Officer understand how it benefits the government.”

The pestering worked. The GSA Division Director seems to have had the contract reassigned and granted the price increase McKinsey wanted. The director also seems to have been lying to the inspector general, as well as manipulating pricing data, breaking rules on sole-source contracting, and pitching various other government agencies, like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, to buy McKinsey services. Eventually, the director straight up said, “My only interest is helping out my contractor.”

From 2006, when McKinsey signed its original schedule price, to 2019, it received roughly $73.5 million/year, or $956.2 million in total revenue from the government. The inspector general estimated the scam from 2016 onward would cost $69 million in total overpayments. It’s a scandal. But still, something about it doesn’t quite make sense. Why would a government division director at the GSA seek to increase costs for the government? It’s not bribery, since the IG didn’t recommend firing or arresting the government official who pushed up costs (or at least that’s not in the IG report).

The Industrial Funding Fee

And this gets to the second reason why McKinsey can charge so much, which has to do less with McKinsey and more with an incentive to overpay more generally. It’s more likely something called the “Industrial Funding Fee,” or IFF. The GSA’s Federal Acquisition Service gets a cut of whatever certain contractors spend using the GSA’s schedule, and this cut is the IFF. The IFF is priced at 0.75 percent of the total amount of a government contract. In the case of McKinsey, since 2006, “FAS has realized $7.2 million in Industrial Funding Fee revenue.”

In other words, the agency of the government in charge of bulk buying isn’t paid for saving money, but for spending too much of it. The IFF also incentivizes the GSA to get the government to outsource to contractors anything it can, simply to get more budget. The IFF has been creating problems like the McKinsey over-payment for a long time. In 2013, the GSA Inspector General traced a similar situation with different contractors. Managers at GSA overruled line contracting officers to raise prices taxpayer pay for contractors Carahsoft, Deloitte and Oracle. Government managers at GSA micro-managed and harassed their subordinates and damaged the careers of contracting officers trying to negotiate fair prices for the taxpayer.

How did the GSA get such a screwed up incentive as the Industrial Funding Fee? Well, in 1995, to get the government to become more entrepreneurial as part of its “Reinventing Government” initiative, Bill Clinton’s administration implemented the Industrial Funding Fee structure. It worked in generating money for the GSA. It worked so well that Congress’s investigative agency found in 2002 that the GSA stopped having to rely on Congressional appropriations. It had so much extra money that it started to spend lavishly on its “fleet program,” which is to say vehicle purchases. In other words, the GSA earned so much money by outsourcing the work of other government agencies to high-priced contractors that it just started buying fleets of extra cars.

By 2010, GSA had “sales” of $39 billion a year. While the GSA is supposed to remit extra revenue to the taxpayer, it often just stuffs the money into overfunded reserves. More fundamentally, the culture of the procurement agencies of government has been completely warped. The GSA’s entire reason for existing was to do better purchasing for the government, using both expertise and mass buying power to get value. But now officials try to generate revenue by getting the government to spend more money on overpriced contractors. Like McKinsey.

Does McKinsey do a good job? The answer is that it’s probably no better or worse than anyone else. I’m sure there are times when McKinsey is quite helpful, but it’s in all probability vastly overpriced for what it is, which is basically a group of smart people who know how to use powerpoint presentations and speak in soothing tones. You can just go through news clippings and find areas McKinsey did cookie-cutter nonsense. For instance, McKinsey helped ruin an IT implementation for intelligence services. In the immigration story, MacDougall shows that the consulting firm encouraged ICE to give less food and medical care to detainees. That’s cruelty, not efficiency.

Still, it’s not all on McKinsey. The Industrial Funding Fee is one reason paying $3 million a year for a 23-year old McKinsey employee instead of hiring an experienced person directly to do IT management has some logic to a government procurement division head. The policy solution here is fairly simple—kill the IFF fee structure and finance government procurement agencies through Congressional appropriations directly. Also, follow the IG’s recommendation and cancel McKinsey’s contracting schedule.

At any rate, at some point decades ago, we decided that most political and business institutions in America should be organized around cheating people. In this case, the warped and decrepit state of the GSA leads to McKinsey-ifying the entire government. Mr. Clinton, you took a fine government that basically worked, and ruined it. McKinsey sends its thanks.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this article appeared in BIG, Matt Stoller’s newsletter on the politics of monopoly. You can subscribe here. Matt Stoller is the author of Goliath: The Hundred Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy and a fellow at the Open Markets Institute.

The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.