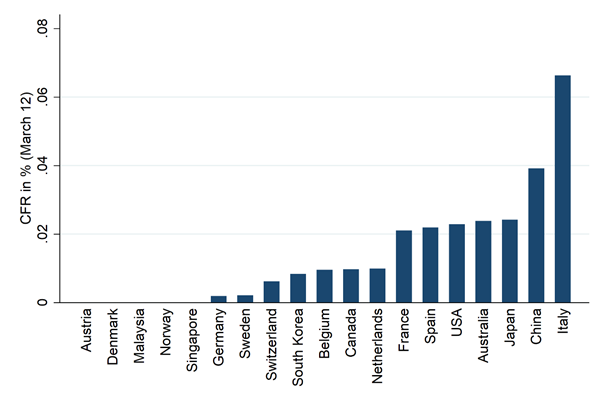

Italy has a mortality rate of 6 percent while countries like Norway, Denmark, and Germany have rates still close to zero percent. The structure of social interactions seems to clearly matter. Therefore, social distancing needs to regard the elderly in particular.

We have been thinking about the big differences in mortality rates so far during the coronavirus outbreak in Europe. The differences in case-fatality rates are humongous. Italy has one of 6 percent while countries like Norway, Denmark, and Germany have rates still close to 0 percent.

Of course, the rates will likely converge somewhat over time as the virus spreads and there are many effects in this. Division bias may play a role, as does the time since the outbreak.

However, we thought maybe there is something to learn in this in order to help to organize our lives in a way to minimize the risks for us and those we pose to others. We picked up a striking data difference that Andreas Backhaus pointed out.

(4) More countries? Germany @rki_de has published ages of 648 cases, but (of course) on a different age scale. Aggregating age groups a bit more shows that DE has an even lower share of old people among the infected than SK (and has also had fewer deaths, only 3 so far). pic.twitter.com/ILQSYUFukD

— Andreas Backhaus (@AndreasShrugged) March 11, 2020

It has been established now that, importantly also unlike the Spanish flu, COVID-19 is particularly deadly for the elderly and disproportionally creates the need for intensive care in these groups.

Medical research and treatment are front and center to combatting this crisis and as scientists, we believe in the power of medical research and science. Yet, we as social scientists thought how we can also add something to combatting the crisis. We have been thinking, why is it that in some countries more elderly people are infected than in others?

Our hypothesis is that differences in social interactions and social networks might play a key role. These differences might stem from cultural or institutional differences across countries.

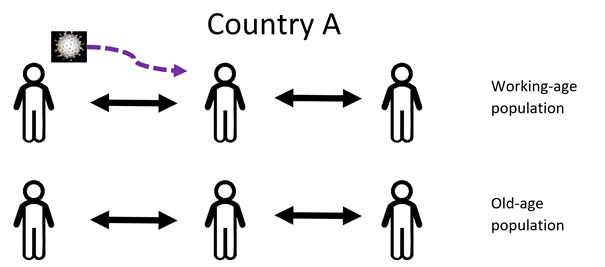

The idea is simple. Suppose that in Country A almost all interaction is within one group of people, i.e. working-age people hang out amongst themselves, and a second group of people, the elderly, do the same.

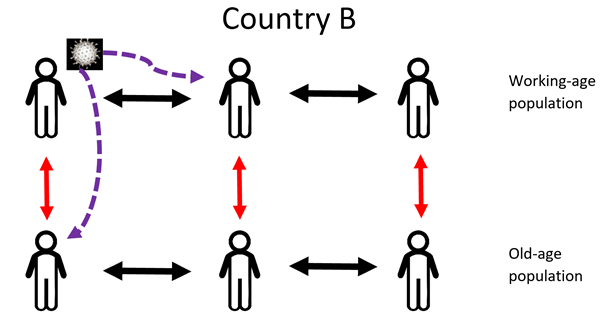

At the same time, in Country B, interaction is often across generations. The young and the old live together and interact, for example, by taking care of grandchildren or young workers who still live with their parents as they cannot afford to live on their own.

Since coronavirus was likely “imported” to Europe, mostly through work-related travel, a country of type A should initially see a much more contained outbreak, with much less need for intensive care and much fewer fatalities relative to the size of the outbreak.

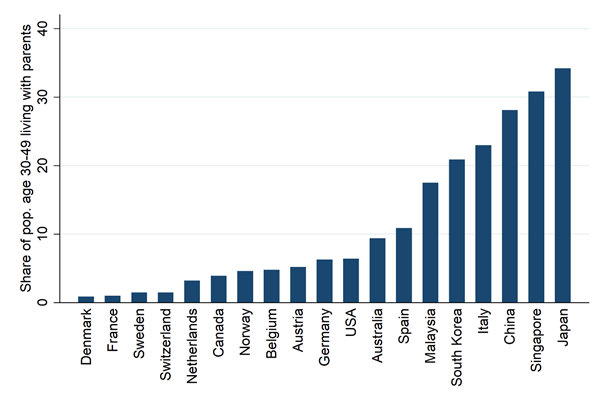

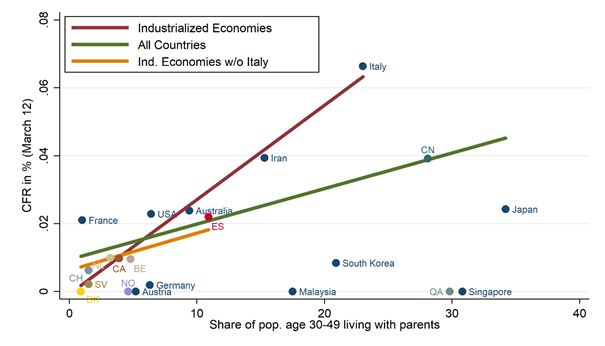

Given this hypothesis, we asked how we could operationalize this idea. So we turned to the World Value Survey data and calculated from this source the share of people between age 30-49 who live with their parents.

This share varies dramatically across countries. From shares below 5 percent in countries like France, Switzerland, and the Netherlands, to cases like Japan, China, South Korea, and Italy with shares above 20 percent.

If we take this share as a measure of intergenerational interaction (how many red arrows there are), then already a simple figure highlights our key idea. Here is what it looks like when we plot it against the case-fatality-rate (CFR) for all industrialized economies with more than 100 cases (as of March 12)

Italy is surely an outlier in both dimensions, and the CFR will hopefully go down in the end. However, what the graph tells us is that the structure of social interactions seems to clearly matter and that social distancing needs to regard the elderly in particular.

Potentially, this effect will also go away over time as the virus finds its way into the elderly population and can then spread within because of course the elderly are also a socially connected set of people.

Those countries with low fatality rates, like Germany, should take this as a warning sign. The low initial fatality rates are unfortunately likely not here to stay once the virus spreads.

At the same time, we hope this little bit of data analysis helps us to better understand how pivotal it is to keep the elderly uninfected and what role social networks and links play in this.

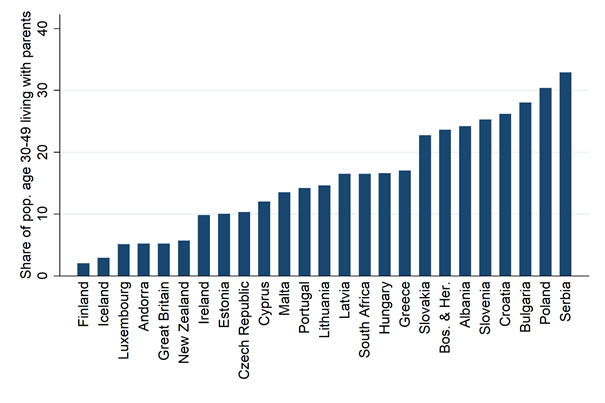

What is more, it may provide a warning sign for those countries where the elderly and the young live close together as to how important it is to contain the virus there early on. These countries are in Europe in particular, such as Serbia, Poland Bulgaria, Croatia, or Slovenia.

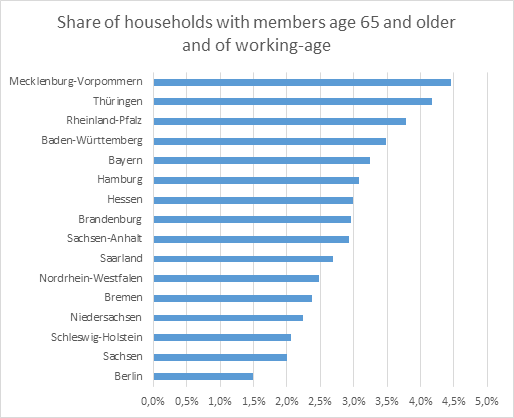

We also looked at the share of households with members aged 65 and older living with working-age family members (aged 30-49 as before) across states within Germany.

Also within Germany, we find some noticeable variation that might provide an early warning sign to policymakers in some of the heavily-affected states like Bayern and Baden-Württemberg.

As social scientists, we know how important behavioral responses to changes in the environment are. Indeed, this is what we strongly hope for, and in the best case where people reduce social interactions, contagion might go down and keep the number of deaths low as well.

The crisis might be much less severe than what we predict today, but only if we react to the situation in due time.

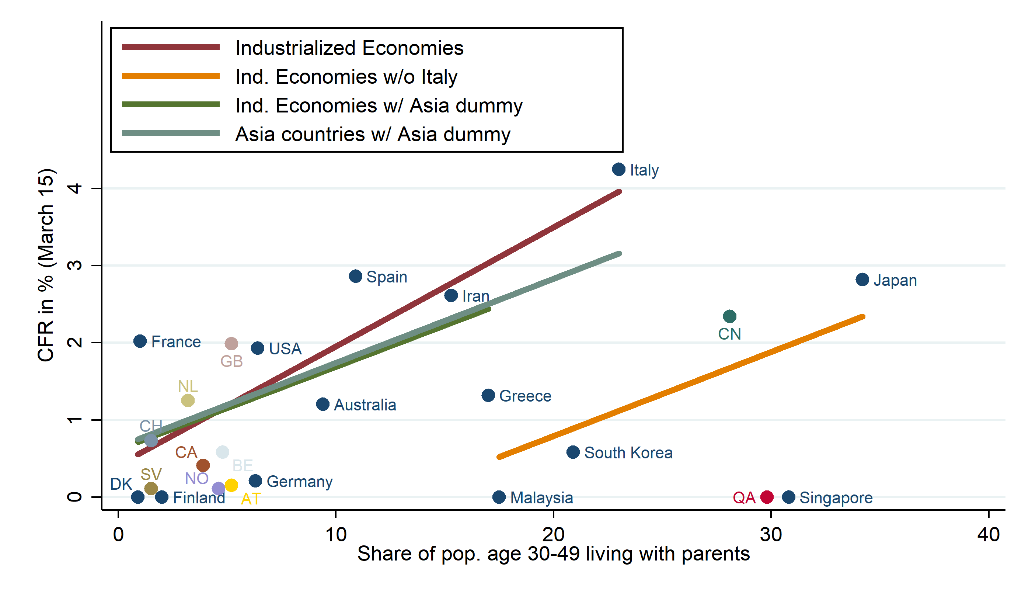

We updated our data recently to March 15: We also took into account that public health systems started to overload that likely increased CFRs further. Therefore we restricted our sample to the period when the total number of diagnosed cases was still below 5,000 cases in the respective country.

Now, only a few days later, further countries had large case numbers and therefore entered our sample, yet, the picture remained the same.

We also refined the specification and allowed for a different relationship for the East Asian countries. In this case, we find the same correlation between social interaction and CFRs within the two country groups (green and light blue line).

Christian Bayer is a Professor of Economics at the University of Bonn. He is a macroeconomist whose research focuses on investments of firms and household savings in environments with heterogeneous agents, on worker, job-, and firm dynamics, as well as the macroeconomic implications of financial frictions.

Moritz Kuhn is a Professor at the Department of Economics at the University of Bonn. He received his Diploma in economics from the University of Mannheim in 2005 and his PhD from the University of Mannheim in 2010. His current research focuses on labor economics and the link between income and consumption risk.

Editor’s note: This article is an edited version of a Twitter thread by Kuhn.

ProMarket is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.