The Italian experience suggests that locking downtowns is a necessary but insufficient condition to stop the spread of the disease. If 50 percent of the infected are asymptomatic, there is no hope of containing the disease unless we subject ourselves to massive testing. On February 22, 3 percent of the inhabitants of Vo Euganeo, a small town close to Padua, were infected. After two weeks in which the town was locked down and a massive testing program applied, only 0.25 percent were infected.

Many people have asked me what the rest of the world can learn from Italy’s struggle with COVID-19. I am not an infectious disease specialist, but I have spoken to Italian specialists and tried to analyze all available data. I am sharing my conclusions here, ready to be corrected by those who know more than I do.

The bottom line is very simple: many people who contract the disease are asymptomatic. On the one hand, this is good news because it reduces the predicted death rate. On the other hand, it suggests that testing only symptomatic people will not stop the spread of the disease. Generalized testing and two weeks of lockdown could work, but the latter without the testing may be insufficient. Unfortunately, the United States is going down the wrong path.

The Vo’ Euganeo Experiment

Vo’ Euganeo is a small town (3,341 people) located on the hills just outside of Padua (the town where I grew up). It came to international prominence on February 21, when Adriano Trevisan, a 77-year-old inhabitant, died of coronavirus.

Yet, what will ensure Vo’ Euganeo a place in the history of medicine is the decision made by the Governor of the Veneto region (which includes Padua, Venice, and Verona) to test all 3,341 inhabitants of the town twice: the first time before closing it off from the rest of Italy and a second time two weeks later.

In this respect, Vo’ Euganeo is similar to the Diamond Princess, the ship quarantined in the port of Yokohama, even in population size (3,711). In both cases, we can observe an entire population exposed to the virus over time, with comprehensive testing.

This is different from all the other cases, where only a fraction of the population is tested and that fraction is likely to be the one showing some symptoms of the disease.

The first piece of good news coming out from both these ‘experiments’ is that more than 50 percent of the documented COVID-19 cases are asymptomatic cases, similar to what researchers found in the Diamond Princess case.

Once we adjust for this percentage, we have the second piece of good news: in both these samples, the case mortality rate (CMR)—the fraction of cases that die after contracting a disease—is “only” 1 percent (1 percent in Vo’ and 1.1 percent in the Diamond Princess after adjusting for the age distribution).

This is ten times the CMR of normal influenza, but it is less than a third of the CMR 3.4 percent estimate of the World Health Organization and almost one-tenth of the CMR reported in Lombardy, the Italian region around Milan, which is one of the richest and more technologically advanced regions in the world.

To validate this estimate, I use a country less likely to miss asymptomatic COVID-19 cases. Between February 21 and February 26, South Korea increased the number of tests conducted per day from 1,400 to 14,000, reaching 210,000 tests performed as of March 9.

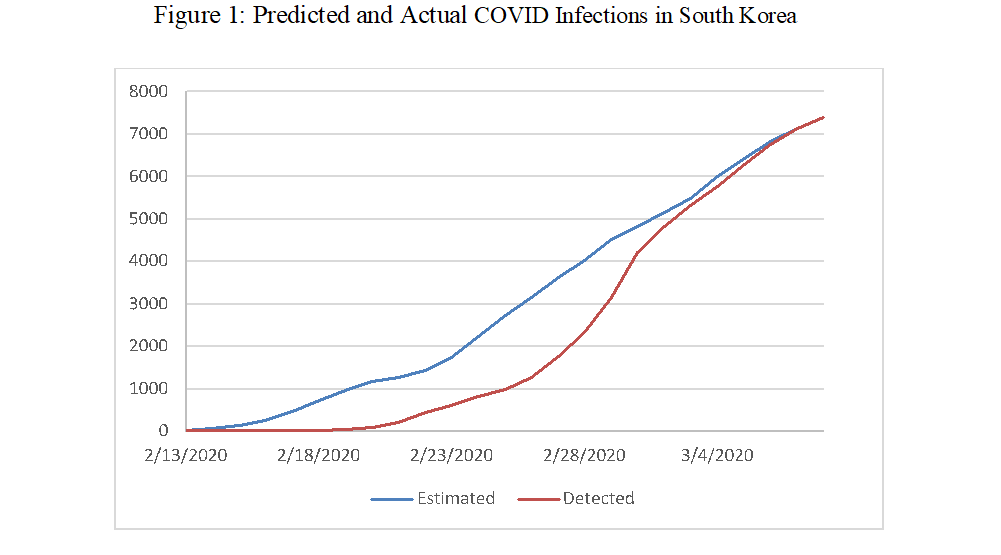

Given the number of tests conducted, South Korea should have been able to identify most cases of COVID-19 present on its territory. If this is true (and the 1 percent CMR is correct), today’s deaths divided by 0.01 should equal the number of cases detected nine days before (assuming people die 8.6 days after detection). Figure 1 below plots the two series:

In the last two weeks, the number of deaths predicts well the number of infections detected nine days before. This is not true, however, in the middle of the sample, when the number of tests conducted was much smaller.

Thus, the estimated number of cases in the middle of February is probably closer to the actual number of cases than the number of detected cases.

As we can see from the picture, the rapid rise in the number of cases in late February is purely a detection effect. As the number of tests increases, detected cases go up, but actual cases do not go up at the same rate.

To understand what works in containing the spread of the disease, we need to have an accurate count of the infected. In places other than South Korea, reported infection numbers differ wildly from the actual rates of infection and this difference might change over time with changes in testing policies.

The lesson from Vo’ and from the Diamond Princess suggests that the number of deaths nine days later is a much better predictor of the diffusion of the disease.

What Does This Say About The Spreading of the Virus?

The above conclusion is very important to help us estimate the spread of the disease in the United States, where testing has been very sporadic (to use a British understatement). Yet, I will leave the application to the United States for another day and focus on what we can learn from the Italian case if we use this estimator.

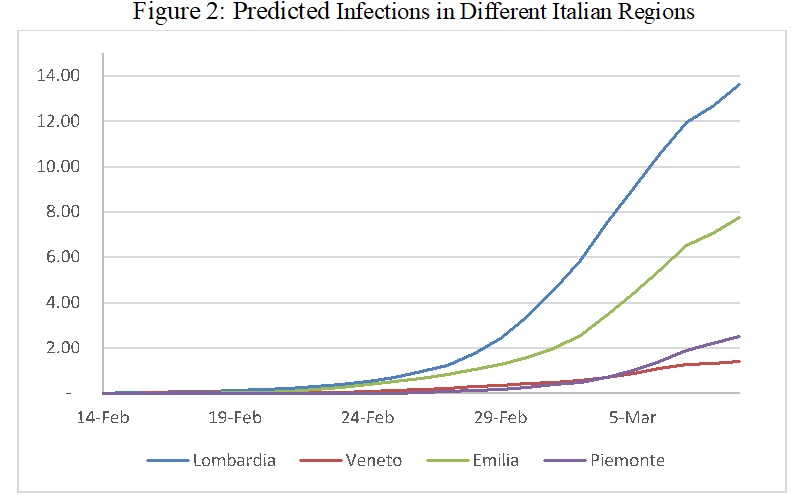

Figure 2 plots the spreading of the virus in the four main Italian regions, where the diffusion is measured by deaths nine days later divided by 0.01 (I use a three-day moving average to smooth the number of fatalities). If we apply this method to the top four regions of Northern Italy and we divide the number of estimated infected by population in the region (in thousands), we obtain the following picture:

Lombardy was probably the epicenter of the initial contagion. Hence, the quick rise. Yet, Veneto (which experienced its first death the same day as Lombardy) seems to have a growth of infected people much slower than the other main Northern regions.

In particular, the absolute and relative level of deaths in Veneto is inferior to those in Emilia and Piemonte, in spite of the fact that these two regions experienced their first deaths several days after Veneto.

The Veneto Model

There is an important difference between Veneto and the other three Northern regions. From the beginning, Veneto applied the strategy of mass testing applied in South Korea. As a result, Veneto has been able to isolate infected people even when they were asymptomatic. In Vo’, this strategy worked wonderfully.

On February 22, 3 percent of the inhabitants of Vo’ were infected. After two weeks in which the town was locked down, only 0.25 percent were infected. Once these few infected people were isolated, the town reopened and has experienced no new cases.

Compare this strategy with the one adopted in the Diamond Princess. Initially, passengers and crew members were tested as they were showing symptoms and only after that they were taken off the boat.

Only toward the end did the authorities test all the passengers. As a result, what started with the infection of one passenger eventually contaminated 20 percent of the people on board. Thus, in one case we go from 3 percent to none, in the other case from 1 to 20 percent.

Implications for the United States

The Italian experience suggests that mass testing is a necessary component of a successful strategy against COVID-19. You have to test early and you have to test as many people as possible to isolate the infected. That is the opposite of the US strategy.

Why was the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) so late in developing a test? Why, to this day, does it have very strict guidelines restricting the number of people who are tested?

Talking about the vaccine (not the test), Alex Azar, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, stated: “we work to make it affordable, but we can’t control that price because we need the private sector to invest.” Is the CDC trying to save money or to help the private industry make a profit?

I strongly believe that monetary incentives are important to get the private sector to invest; but in a national emergency, the CDC should be able to develop its test fast and to roll it out for free to the nation, like all other developed nations did.

If the most expensive healthcare system in the world is unable to do so, the time has come to rethink it from the ground up.

ProMarket is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.