In this installment of ProMarket’s interview series on concentration in America, Cornell University professor Roni Michaely shares data on rising concentration in the U.S. economy.

Does America have a concentration problem? On March 27-29, the Stigler Center hosted a first-of-its-kind, three-day conference in Chicago that focused on this very question.

The conference brought together dozens of top academics from law, economics, history, and political science, policymakers, journalists, and public intellectuals. Ahead of this conference, we presented influential scholars and thinkers with some questions on concentration, market power, and bigness—and their potential effects on the U.S. economy.

You can read all previous installments here.

Roni Michaely is the Rudd Family professor of finance at the Johnson Graduate School of Management at Cornell University. He teaches corporate finance and entrepreneurial finance at the Cornell-Tech program in New York City.

Professor Michaely’s research interests are in the areas of empirical corporate finance, payout policy, corporate governance, and entrepreneurial finance. His current research focuses on conflicts of interest in the capital markets, corporate payout policy, and the structure and behavior of both public and private firms. He was recently recognized as one of the most cited people in finance, and just finished serving a four-year term as an associate editor for the Journal of Finance.

Michaely served as a director of the Israeli Securities Authority (ISA) from 1998 to 2003 and is involved in consulting on issues like restructuring and trading strategies. He currently sits on the board of several startups including Tipranks, and Urbanr and on the advisory board of TPY, a VC firm.

In a brief interview with ProMarket, Michaely shared observations and data on rising concentration in the U.S. economy.

Q: The discourse on concentration, market power, and bigness in many U.S. industries has increased dramatically in the last year. Do you believe that we have enough empirical evidence to show that concentration is on the rise and having adverse effects on the economy?

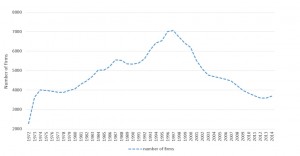

Yes. I think there is unambiguous evidence that concentration is on the rise. This rise in concentration is widespread over most industries. For example, see figures 1 and 2:

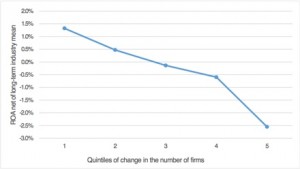

What we find is a significant increase in return on assets and in profit margins of firms in industries that have become more concentrated. This means that those firms are able to charge higher prices (relative to cost of production) and have greater surplus. This is likely at the expense of consumers. See figure 3:

Q: In your opinion, what are the main reasons for the rise in concentration?

We find two possible—and perhaps likely—reasons. The first is the decline in antitrust enforcement since the later 1990s. The second—which is very much related—is the higher barriers to entry created by technological changes and by the high fixed costs they impose, making it harder for new firms to enter the industry.

Q: Which industries should we be concerned with when we look at questions of concentration?

Industries where (expensive) technologies are a significant factor. In fact, in my honest opinion, this is relevant to many industries, as technology affects inventory management, deliveries, quality control, predictive maintenance, etc.

Q: Has consolidation in the financial industry played a role in concentration or antitrust issues in the U.S.?

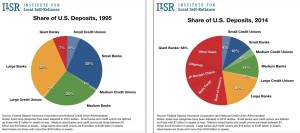

Possibly. First, the financial service industry has gone through significant consolidation itself, giving it more direct market power. For example, see figures 4 and 5:

Second, this market power has likely

enhanced their lobbying power even more, allowing them to make a case of lesser regulations—not only for the financial services industry, but overall. They surely benefit from M&A activity and the additional borrowing associated with many of the mergers.

Q: The five largest internet and tech companies—Apple, Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Microsoft—have outstanding market share in their markets. Are current antitrust policies and theories able to deal with the potential problems that arise from the dominant positions of these companies and the vast data they collect on users?

This is not directly related to my research, but my reading is that U.S. antitrust policy is less concerned with the creation of giant firms, relative to Europe. I do not see any serious proposal to break-up Google, for example.

As these giants gather more and more data on users (consumers, producers, etc.) and have more sophisticated analytical techniques, and as they have a greater consumer base as captive audience, most of them are likely to grow even further and become even more dominant. It will become even harder to compete with them, or for newcomers to penetrate those industries.

Q: Is there a connection between the growing inequality in the U.S. and concentration, dominant firms, and winner-take-all markets?

I think so. This is my next project.

Q: President Trump has signaled before and after the election that he may block mergers and go after certain dominant companies. What kind of antitrust policies should we expect from him? Pro-business, pro-competition, or political antitrust?

He may try to block a merger or two for PR, but I expect him to be very pro-big business. What I have seen so far (including cabinet picks, lower taxes etc.) suggests to me that his administration is likely to exacerbate the situation even further. In other words, in four years we will see big firms becoming even bigger and industries becoming more concentrated.