The recent revelations regarding the interactions between Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel and former Uber executive and Obama adviser David Plouffe suggest that the real action in the U.S. lobbying game takes place under the surface. The billions of dollars invested in lobbying every year, and the thousands of registered lobbyists, are only the tip of the influence-peddling iceberg.

In August 2014, David Plouffe was appointed as Senior Vice President of Policy and Strategy at Uber, a position he held until May 2015 when he became a Strategic Advisor for the company. The word “Lobbyist,” however, never appeared in his job description.

Before joining Uber, Plouffe held high profile and successful positions as the manager of President Obama’s 2008 campaign and later as his advisor in the White House. “Lobbyist” did not appear in Plouffe’s job title in Uber, nor in his former jobs: It was only in April of 2016 that Plouffe had to register himself as a lobbyist with the Board of Ethics of the city of Chicago.

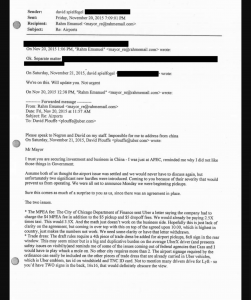

Plouffe’s work as a lobbyist for Uber was revealed almost by accident, when the Better Government Association, a Chicago-based watchdog focused on government and public officials in Illinois, pushed for the public release of emails that Mayor Rahm Emanuel sent and received from his personal email account while in office. Among many other things, the emails revealed that, during 2015, Emanuel and Plouffe exchanged emails regarding an important business interest of Uber.

The real nature of Plouffe’s job is not surprising, considering his career path and the business model of Uber.

Uber, the omnipresent ride hailing company, is also one of the most valuable still-private startups in the world. As public rides are heavily regulated in most markets, Uber’s core task is to convince the many national and local regulatory agencies in its various markets to let its drivers pick up passengers on favorable terms compared to the incumbent services, which are usually very powerful, politically-connected special interest groups. Although Uber is often hailed as a technology company, it is actually a regulation play. Regulation is not just an important part of the business model, it is the most important part.

Over the years, Uber has increased its lobbying spending considerably and earned itself a reputation for being very aggressive in its dealings with regulation. According to OpenSecrets.org, from 2013 until 2016 Uber’s spending on lobbying ballooned from a mere $50,000 to $1,360,000.

But these numbers, which get a lot of visibility in the media on a daily basis, probably dramatically underestimate the size and clout of the U.S. Lobbying-Industrial Complex. They do not account for state and municipal lobbying like in the Plouffe-Emanuel case, and more importantly, they don’t account for the vast activity that takes place in PR, “Strategic,” “Advisory,” and “Consulting” firms, and the individuals who are engaged in lobbying directly with lawmakers, regulators, and opinion leaders.

Uber is a good example: OpenSecrets’ numbers look miniscule compared to the lobbying activity that was exposed by investigative journalists. In a December 14, 2014 article in The Verge titled “Uber Has an Army of At Least 161 Lobbyists and They’re Crushing Regulators,” reporter T.C. Sottek wrote: “Part of [Uber’s] success—and what Uber makes headlines for—comes from its ruthless playbook to frustrate the competition and to invade any market it wants, even if it’s facing a government-protected taxi monopoly. Less glamorous but no less important: Uber appears to be completely dominating local politicians who get in its way.”

Six months later, on June 24, 2015, Bloomberg Businessweek’s Karen Weise published an article, “This Is How Uber Takes Over a City,” where she described the ferocity in which Uber tackles regulation. “Over the past year,” Weise wrote, “Uber built one of the largest and most successful lobbying forces in the country, with a presence in almost every statehouse. It has 250 lobbyists and 29 lobbying firms registered in capitals around the nation, at least a third more than Wal-Mart Stores. That doesn’t count municipal lobbyists. In Portland, the 28th-largest city in the U.S., 10 people would ultimately register to lobby on Uber’s behalf. They’d become a constant force in City Hall. City officials say they’d never seen anything on this scale.”

Plouffe fit the bill because of top positions he held in Barack Obama’s campaign and administration. He was the manager of Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign and later, between January 2011 and January 2013, worked again for Obama, this time as a Senior Advisor.

While at Uber, as can be expected from his job title, he helped the company tackle some regulatory issues. One such issue had to do with Uber’s plans to pick up passengers in Chicago’s two international airports, O’Hare and Midway. O’Hare is the fourth busiest airport in the world. In 2016, 78 million passengers went through it. In 2016, Midway’s traffic totaled 22 million passengers. Their combined traffic would put them close to the busiest airport in the world, Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson airport.

One of the top figures Plouffe communicated with regarding this issue was Emanuel, who is also a former close Obama ally: between January 2009 and October 2010 he was Obama’s Chief of Staff. Also, Emanuel’s brother, Hollywood talent agent Ari Emanuel, is an Uber investor. Later, in August 2016, Uber hired Emanuel’s former chief of staff Lisa Schrader. Her LinkedIn profile states that she is currently Uber’s Director of Public Affairs in Central U.S.

Even though Emanuel is a highly visible public figure holding an elected office, his connection with Plouffe was not readily visible. The exchange between the two was revealed in December 2016 following two open records lawsuits that alleged that Emanuel violated Illinois open records laws. It then also became apparent that Emanuel used non-governmental email accounts to communicate with Plouffe.

Two months later, the Chicago Board of Ethics, to which all lobbyists report, ordered Plouffe to pay $90,000 in fines because he was not registered as a lobbyist when he contacted Emanuel.

Chicago’s definition of lobbying is easy to understand as it is broad: “Lobbyist,” the definition reads, “means any person who, on behalf of any person other than himself, or as any part of his duties as an employee of another, undertakes to influence any legislative or administrative action.” This includes, but is not limited to, ten types of activities, such as zoning, concession agreements, and the solicitation, award or administration of a contract.

Currently, the city’s Board of Ethics’ lobbyist list has 8,518 records, two of which belong to Plouffe—one in which his listed employer is Uber and one with no listed employer.

In its decision regarding Plouffe, the Chicago Board of Ethics wrote that “The evidence before the Board is clear: Mr. Plouffe lobbied City officials via email on November 20, 2015, explicitly on behalf of the company, never reported that lobbying activity, and did not register as a lobbyist with the Board of Ethics with that company as his client until April 13, 2016—leaving a total of 95 business days between the date of lobbying and the date of registration.”

Passengers landing in O’Hare are probably happy with the outcome of Plouffe’s successful Lobbying, as Uber rides are significantly cheaper than taxis. But the bigger question here is: Should lobbying be allowed behind closed doors without any transparency and disclosure?

The Plouffe-Emanuel incident is not the only one in which Uber ended up with a fine related to problematic lobbying practices: just recently, on January 5, the Portland, WA, city auditor fined Uber $2,000 for failing to disclose that political consultant Mark Wiener was working as a lobbyist on its behalf in late 2014 and early 2015.

Plouffe’s decision to not register as a lobbyist with the Chicago Board of Ethics until April of last year is not unique. It is only the latest high profile case in an ecosystem whose true nature is that it’s filled with people who are known as “advisors” and “strategists” of large companies whose business models rely heavily on favorable government regulation. This is the world of Hidden Lobbyists.

Long before Plouffe, there was an even higher-profile figure who did not want to register as a lobbyist: Newt Gingrich.

Gingrich rose to prominence in the second half of the 1990s, when he was Speaker of the House during Bill Clinton’s presidency. Immediately after that, Gingrich founded Gingrich Group, a consulting firm. On January 24, 2012, The Washington Post reported that mortgage giant Freddie Mac paid Gingrich’s company $1.65 million for about five-and-a-half years of consulting work. According to the report, the contract between Gingrich and Freddie Mac included a section that stated that “nothing herein is or shall be construed as an agreement to provide lobbying services of any kind or engage in lobbying activities.” But at the same time, it also made clear that Gingrich’s firm reported directly to Freddie Mac’s public policy and lobbying office, making the previous stipulation less clear.

“Gingrich,” said The Washington Post’s report, “who regularly buttonholed former House colleagues on behalf of pet issues or companies—has insisted he never acted as a lobbyist while running his lucrative post-congressional empire, which brought in an estimated $150 million since 1999.”

Nevertheless, Gingrich was never able to successfully shake off the claims that he was a lobbyist. In fact, In January 2012, a spokesperson for another top Republican, Mitt Romney, issued a release in which he stated that “Speaker Gingrich’s denial of his lobbying work in Washington has reached comical proportions. While he continues to deny that he ever lobbied, he is contradicted by former members of Congress, third-party observers, and even his own surrogates. Speaker Gingrich should come clean with Republican primary voters and address his lobbying work honestly and forthrightly.”

The important role of lobbyists in politics and business in the U.S. is monitored and covered by the news media and by several watchdogs that collect and publish detailed information on lobbyist activities and the huge sums of money that are spent in this industry. But the Plouffe lobbying event, and its almost accidental exposure, are yet another indication that the real action in the lobbying game in the U.S. takes place under the surface. The billions of dollars invested in lobbying every year and the thousands of registered lobbyists are only the tip of the influence-peddling iceberg.

How and when did lobbyists start going underground? How large is the hidden-lobbying complex? And what can be done about it? These questions and others will be discussed in ProMarket’s second installment on hidden lobbying next week.