Compared to 2016, turnout was 22 percent higher (on average) for states voting on Super Tuesday, before Covid-19 emergency measures in the United States. This week, the situation changed dramatically: Average growth across states voting on March 17th was just 3 percent. Here’s how States can promote health-conscious participation in elections and what we can learn from the 1918 Spanish Influenza.

Tuesday, March 17th was a primary election day unlike any other in recent American political history.

Despite global concerns about governments’ capacities to handle the spread of the novel Covid-19 coronavirus, and federal recommendations that Americans avoid gatherings of ten or more people, three states (Florida, Arizona, and Illinois) held in-person primary voting this week. Only one state scheduled to vote this week (Ohio) postponed their election contest.

In this piece, I show that Covid-19 concerns likely decreased voter turnout in the March 17th primaries. I also argue that—while some activists correctly note that the US held midterm elections at the height of the Spanish Influenza pandemic—our thinking about whether or not to reschedule 2020 primaries ought to reflect updated information and concerns about public health and our collective safety. Finally, I discuss some strategies states can take to promote civic participation in a health-conscious way.

Did COVID-19 Decrease Turnout in the March 17th Primaries?

Anecdotally, there is good reason to believe Covid-19 interfered with primary election administration. For example, polling station closures led to delayed start times (and extended voting windows) throughout Cook County, Illinois, including Chicago. In Florida, hundreds of poll workers quit their posts due to fears about potential susceptibility to the virus. Perhaps unsurprisingly, initial reporting from the New York Times indicated that in-person voting was down in all three states that elected to hold primaries, relative to 2016.

This anecdotal evidence, however, doesn’t necessarily mean that overall turnout levels declined. For example, voters might have compensated for concerns about voting in-person on election day by voting early or requesting an absentee ballot.

Additionally, it could be the case that the size of the would-be primary electorate grew large enough (relative to 2016) to still detect a turnout increase, even if health concerns and logistical confusion at the polls kept some people from casting ballots on election day.

To get leverage on this question, I provide a data-driven account of just how much turnout may have declined in these three states, relative to 2016 and in comparison to previous midterm elections held this year (i.e., in weeks before widespread public concern about the virus’ impact on life in the US).

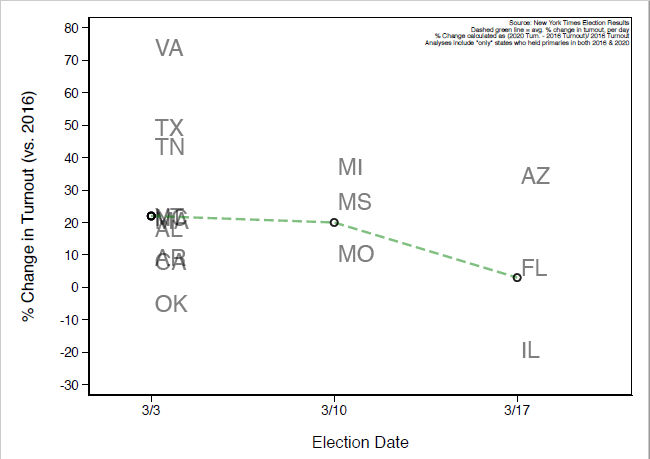

The figure below plots the percent change in turnout for each state that voted on Super Tuesday (3/3), “Big” Tuesday (3/10), and this week (expressed as state abbreviations, in the figure). The dashed green line presents that average increase in turnout (relative to 2016) for each group of states voting on that day.

Before diving into the results, there are four important things to note about this figure. First, it excludes states that switched from a caucus system to a primary system on 3/3 (e.g., Minnesota) and 3/10 (e.g., Colorado), as differences in administration procedure may be responsible for large changes in the number of people who participate.

Second, these estimates include all forms of voting; meaning that any decline in turnout we might observe accounts for the fact that some people voted early/absentee. Third, it focuses only on Democratic turnout; as some states canceled their Republican primaries, and because turnout in contests where the outcome is projected to be more-or-less certain (i.e., the result of President Trump’s incumbency) may experience lower turnout.

The results show that, compared to 2016, turnout was 22 percent higher (on average) for states voting on Super Tuesday, and about 20 percent higher for states voting on March 10th. This week, however, amid unprecedented concern about the spread of coronavirus, the situation changed dramatically. Average growth across states voting on March 17th was just 3 percent.

While Arizona experienced a substantial increase in turnout relative to 2016 (approximately 30 percent), Florida experienced virtually no growth (approximately 2 percent). Critically, Illinois experienced nearly a 24 percent decline in turnout relative to 2016.

Should States Reschedule Elections?

With fewer Americans participating in the electoral process, and concerns about the threat in-person voting could pose for public health, I want to reflect on whether or not it is worthwhile to reschedule future elections.

Supporters of maintaining the current primary schedule argue that voting ought to be considered an “essential” service, much like a hospital or a pharmacy. Joe Biden’s campaign team, for example, noted that the country continued to hold elections during crises like the 1918 Spanish Influenza outbreak.

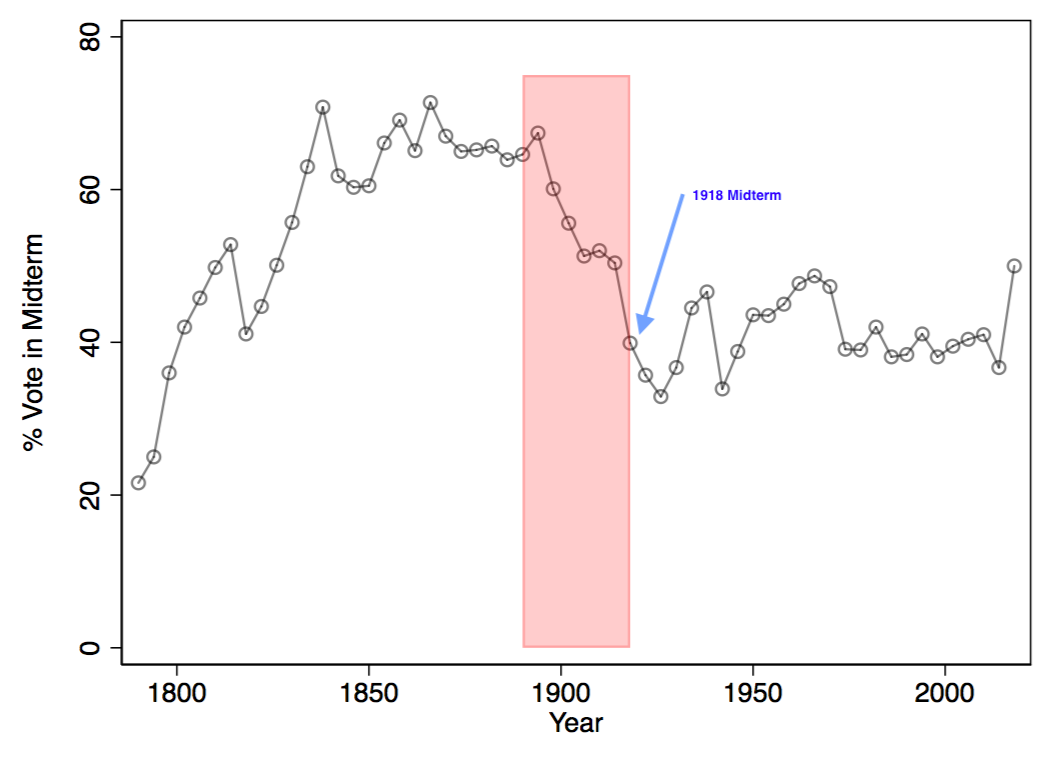

Although states did not yet hold primary election contests in 1918, it is unlikely that the Spanish Influenza was responsible for low levels of turnout in the 1918 midterm election. I illustrate this point below by plotting turnout in every US Midterm election cycle, based on data assembled by the US Election Project.

The figure shows that turnout certainly declined in 1918 (see the blue arrow) relative to the 1914 midterm election cycle. However, it seems unlikely that the Spanish Flu alone is responsible for this decline. Midterm turnout had been on the decline for several cycles prior to 1918 (see the shaded area in red), a trend that cannot be explained by the 1918 pandemic.

Moreover, turnout continued to decline for several years after the pandemic subsided. Consequently, while it’s certainly possible that the outbreak played some role in leading people to stay home on election day, the 1918 midterm was one in a long line of cycles that experienced declining turnout.

Still, there’s much more at stake than just voter turnout. That should give us pause when considering whether or not to move forward with the current election calendar.

For example, public health experts, in part because of lessons learned from the 1918 Spanish Flu, better understand how disease spreads and how to contain it. Social distancing and confinement could save tens of thousands of American lives.

Moreover, analyses from the US Election Assistance Commission find that a majority of individuals who work at in-person polling precincts are over the age of 61, and therefore at high risk of experiencing severe consequences from contracting the virus.

Polling places can take precautions to incentivize social distancing (e.g., fewer polling booths), and provide poll workers with basic sanitation equipment. However, these measures do not rule out the possibility of disease contraction. Moreover, anecdotal reports suggest that some polling precincts either did not (or could not) provide poll workers with basic sanitation supplies.

How Can States Promote Health-Conscious Participation in Elections?

One way that states can promote effective political engagement could be to offer all voters the opportunity to vote by mail as an alternative to in-person voting. In this setup, states could mail all eligible voters a ballot that they could fill out at home, and send back to their local election board.

States could also increase the amount of time individuals have to request and fill-out absentee ballots, prior to election day, and to remove restrictions on who can request them. Some states with upcoming primaries (e.g., Rhode Island) require would-be voters to testify as to why they cannot turn out in-person on election day to vote. In states without no-excuse absentee voting, the coronavirus outbreak could serve as a viable state-wide excuse for being unable to vote in person.

Elections are the lifeblood of American democracy. Yet, in these unprecedented times, it is important to ensure that elections are carried out responsibly, and with an eye toward our collective health.

Mark Motta is an Assistant Professor of Political Science (American Politics, Research Methods) at Oklahoma State University in Stillwater, OK.

ProMarket is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.