Aaron Director, who died 15 years ago, made important contributions to the analysis of business practices. None were ever published under his name. Professor Sam Peltzman explains why his approach was so fruitful.

Aaron Director was born in Charterisk, which is now in Ukraine, in 1901. He died in Los Altos Hills, California, on September 11, 2004. His life was long, his vita was short, and his influence on U.S. antitrust policy was profound. He was the intellectual progenitor of what is sometimes called the “Chicago School” of antitrust policy. Some of the seminal contributions of this school appeared in the Journal of Law and Economics, of which Director was the founding editor. In this memorial essay, I will review his life briefly, but I will focus mainly on his contribution to the economic and legal analysis of antitrust issues.

From an Early Infatuation With Socialism to Chicago

Aaron Director came to the United States in 1913 with his family. He spent his formative years in Portland, Oregon, where the family ran a furniture store. In 1921 he was awarded a scholarship to attend Yale University, from which he graduated in 1924. At this time of his life, Director fancied himself a socialist and conducted himself accordingly, dabbling at various blue-collar jobs and teaching at a school affiliated with the Oregon Labor Party. These radical beliefs were eventually to be altered radically. This pattern of early infatuation with socialism and its subsequent rejection was later to be mirrored in several of his influential students.

Director first arrived at the University of Chicago in 1927 with a fellowship to study labor economics under Paul Douglas (co-parent of the Cobb-Douglas production function and later US Senator from Illinois). However, the greater intellectual influence on his life would come from Frank Knight and Jacob Viner. Director was a graduate student and part-time instructor at Chicago until 1934, but he never completed a doctoral dissertation. It was during this period that he persuaded his sister, Rose, to join him as a graduate student, where she met her future husband, Milton Friedman. This was also the time when Milton Friedman, Aaron Director, and fellow student George Stigler formed a powerful tripartite intellectual relationship that was to endure for the entirety of their careers.

Director was in some ways the odd member of this triad. Friedman and Stigler tended to dominate any room they entered; Director was relentlessly uncharismatic. His two friends were masters of the quick repartee; Director was, at least in my memory, slow and thoughtful. Friedman and Stigler tended toward impatience and a desire to move on. By contrast, a conversation with Director could be punctuated by long silences that often began with one question and ended in another.

The Oral tradition of Innovation

The period of Director’s great influence on economics and law began in 1947 with his appointment to the faculty of the University of Chicago Law School. He was the successor to Henry Simons, who served only briefly as the first economist on a major law school faculty before his untimely death. Director retired from the university in 1966 and spent the rest of his life in the Bay Area of California, where he was affiliated with the Hoover Institution.

None of Director’s innovations appear under his own name. They were transmitted in two ways—in the classroom where he co-taught the law school’s antitrust course and from collegial interaction. Director’s conversations with colleagues sometimes resulted in seminal articles. But other of his ideas were broadcast less formally, often by Friedman or Stigler or, later, by Ronald Coase. His influence on the law students was more direct, since some were destined to become influential judges or legal scholars or both. This history raises obvious problems of attribution. When I subsequently link an idea to Director, I will be conveying my sense of the “oral tradition” that produced the idea.

Director’s most important influence on antitrust policy occurred in three areas: predatory pricing, vertical restraints in distribution, and tied or bundled sales of multiple products. These contributions arose out of his broader interest in what is sometimes called “business practices”. These are the myriad ways in which real-world businesses behave differently from the caricature found in textbooks. Those differences sometimes arouse a suspicious response from economists. Visions of “market power” and “deadweight loss” triangles dance in their heads, and some of the suspect practices have been constrained by antitrust policy. Director rejected this kind of intellectual laziness, and he sought, sometimes successfully, to inoculate those around him against it.

Director approached all business practices with a methodology that entailed asking very basic questions and answering them with a rigorous logic that appealed ultimately to facts. The style was verbal—some combination of Socratic dialogue and Adam Smith. This style had the disadvantage of producing few closed-form solutions. But it had the advantage of permitting analysis of the kind of problems that elude simple solutions.

Indeed, I believe that one reason for Director’s lasting influence is that he was able to show that simple judgments about business practices often cannot withstand rigorous scrutiny.I have already alluded to one such judgment—that the default answer to why a hard-to-understand business practice exists is “monopoly” and that the default policy response is “call the cops.”

Director’s academic career coincided with the highwater mark of the influence of that kind of analysis on antitrust policy. Most of the change—in both the way economists analyzed business practices and antitrust policy—would come after his retirement in 1966.

The conditions for predatory pricing

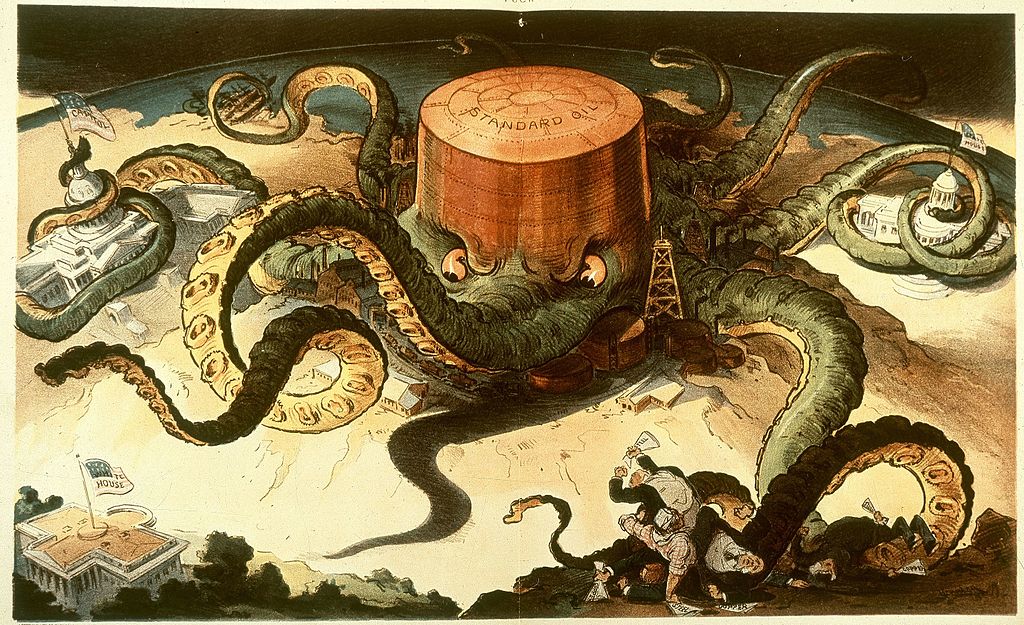

The large firm that crushes small rivals with ruinous bouts of below-cost prices is a durable part of the folklore of American capitalism. The story evokes images of late nineteenth-century robber barons swashbuckling their way to monopolies; the specific example of John D. Rockefeller and the Standard Oil Trust probably comes most readily to mind.

That example is also important because the practice is illegal and played a role in the antitrust case that broke up Standard Oil. The idea that predatory practices of one sort or another are an important source of monopoly continues to exert a powerful hold both inside and outside the economics profession.

The locus classicus of historical revisionism in these matters is John McGee’s article on the Standard Oil case. In this case, we have the author’s summary of Director’s influence on the Article:

I am profoundly indebted to Aaron Director, of the University of Chicago Law School, who in 1953 suggested that this study be undertaken. Professor Director, without investigating the facts, developed a logical framework by which he predicted that Standard Oil had not gotten or maintained its monopoly position using predatory price cutting. In truth, he predicted, on purely logical grounds, that they never systematically used the technique at all. I was astounded by these hypotheses, and doubtful of their validity, but was also impressed by the logic that produced them. As a consequence, I resolved to investigate the matter, admittedly against my better judgment; for, like everyone else, I knew full well what Standard had really done.

The logic that astounded McGee could have come from a dialogue something like this (except that Director rather than McGee would be asking most of the questions):

McGee (JM): Do you mean to deny that a dominant firm would rather have fewer rivals than more?

Director (AD): No.

JM: Do you mean to deny that the dominant firm will be generating more monopoly rents than any small rival?

AD: Let us assume that is the case.

JM: Fine. Cannot the dominant firm use part of its rents to endure a bout of localized below-cost pricing that drives its rival from the market?

AD: Sometimes.

JM: Only sometimes? Then you think there are conditions where predatory price cutting cannot work at all?

AD: Correct. Think of the simplest case: the predator has no cost or demand advantage of any kind over the prey (otherwise it could achieve monopoly without predation). Importantly, it has no cost advantage in accessing capital. In this case, predation cannot succeed.

JM: Why not?

AD: Successful predation means that the predator will be able to recoup short-run losses by generating more monopoly rents than otherwise in the future, enough more to pay, in present values, for the short-run losses. If the predator could succeed in this sense, so too could the prey in this simple case.

JM: How so?

AD: By following a matching strategy. Match the predator’s price. Borrow (at the same marginal borrowing/lending rate as the predator) to finance short-term losses. Wait for the predator to raise price and match that. If the present value of the predator’s cash flows is positive, so too will be that of the intended prey. Indeed, the prey can do even better: the prey can avoid the short-run losses by shutting down and letting the predator enforce the below-cost price. Thus, the simple case involves a logical contradiction—a price path that is at once profitable for the predator and not profitable for the prey.

JM: So predation can succeed only if the predator has some kind of cost advantage.

AD: Correct. But pause to note that if the predator has a cost advantage, then we are back in the case where the predator can achieve monopoly without predation. This should illustrate for you the logical swamp into which predation arguments lead: predation is impossible without a cost advantage and unnecessary with one.

JM: Noted. But let us go on. What kind of cost advantage do you have in mind?

AD: The prey has to face higher marginal borrowing costs than the predator. I could take you further into the logical swamp by asking why the predator has such an advantage. But let’s just assume it’s there and move on.

JM: OK. Why does the success of predation depend on this capital cost difference?

AD: Because the matching strategy will no longer necessarily preclude successful predation. For example, suppose the predator can borrow at (or sacrifice a return of ) 10 percent per year to finance a price war while the prey would have to pay 15 percent. Suppose further that eliminating the prey allows a price increase that generates a gross return of 14.99 percent per year on the funds invested in a price war and that the 4.99 percent margin over the cost of capital is sufficient to make predation more profitable than the status quo. Then predation could succeed, because a 14.99 percent return on 15 percent money cannot be profitable for the prey.

JM: You said “could succeed.” Why not would succeed?

AD: Because the requirements for success are more stringent than I have let on. For example, it has to be the case that all other potential players, including firms in other industries, face 15 percent marginal borrowing costs. If any outsider faces 10 percent, like the predator, the matching strategy rears its ugly head: the outsider will buy the assets, reenter this industry, and match the 14.99 percent price.

JM: But since you do admit that predation might succeed, isn’t it plausible that Standard Oil (and other large firms with lower borrowing costs than rivals or new entrants) fit the requirements for success?

AD: Let us assume so. The case is still not closed.

JM: Why not?

AD: If Standard could win a price war, both it and the intended prey can do better by merging before the war takes place. After all, the main gain from the war goes to consumers who pay bargain prices. By merging, Standard and its intended victim can avoid transferring wealth to consumers and share it for themselves. If you will go back to the record of the case, you should find that merger was a more important source of Standard’s growing market share than predation, and you will find that the prices paid for rivals were hardly stingy.

Apparently McGee took the advice and verified Director’s prediction. Virtually all subsequent discussion of predation must somehow come to grips with the logic summarized above.

That logic is sometimes interpreted as an impossibility theorem. That interpretation is wrong, as Director was always careful to point out. For example, I can recall the day he led his class in a discussion of a case in which the defendant was charged with predation. He sat serenely puffing on his pipe (quite permissible in that era) as he walked us through the damning facts one by one and asked us to interpret each of them. The students, intoxicated by the then-novel McGee article, would try mightily to fit each fact into a non-predation model. But in the end Director brought us to see that the defendant most likely was guilty as charged. And he resisted our desire to inquire further as to why the defendant might have followed a predatory strategy.

The point of that exercise was, I think, to put the theory into perspective. The theory was a guide to the facts, not a substitute for them. The theory did not rule out predation on logical grounds. It did say that the practice would probably not be the typical mode of interaction between firms, just as wars would not be the common outcome of international negotiations nor strikes the usual outcome of labor bargaining. But we needed to be reminded that wars, strikes, and predation did occasionally occur.

Sam Peltzman is the Ralph and Dorothy Keller Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of Economics at the Booth School of Business, University of Chicago. He is also the Director Emeritus of the Stigler Center

This post is an excerpt from the original article published in the Journal of Law and Economics, vol. XLVIII (October 2005) © 2005 by The University of Chicago.

The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.