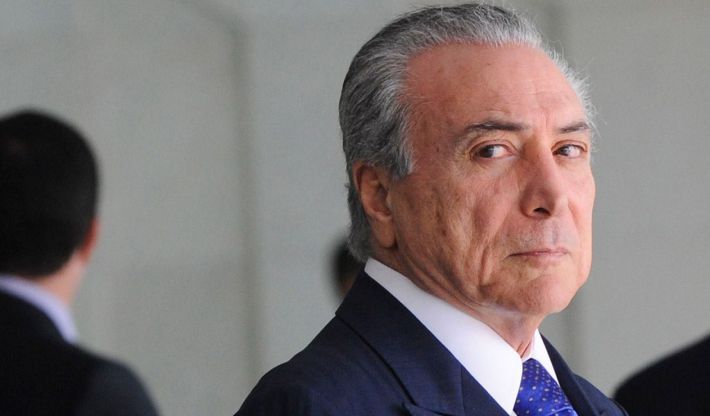

The recently-released secret taping of a conversation between Brazil’s president Michel Temer and one of the country’s most prominent businessmen reveals the extent to which big business influences politics and the judiciary in Brazil.

Brazil never had an image of being a non-corrupt democracy. Last year, the country was ranked 79 in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index. Yet the chain of scandals that rocked the country in the past 2 years, especially the latest spoiled meat scandal one that broke a month ago and made headlines all over the world, has brought a lot of attention to the underbelly of Brazil’s political economy.

The recently-released secret tape of a conversation Brazil’s president Michel Temer and one of the country’s most prominent businessmen reveals the extent to which big businesses influence politics and the judiciary in Brazil. One particularly interesting segment of the tape reveals another major issue currently playing out in Brazil’s political economy that usually gets very little attention, if any.

In the tape, businessman Joesley Batista is heard saying: “I am glad I have a good relationship with the media. So day one [there is a story], day two [another story], day three and…All quiet again.”

That is how Batista, the man who poured gasoline on the fire that is Brazilian politics, explained his relationship with the media to Temer. Batista–one of three brothers at the helm of JBS, the world’s largest meatpacking company–was taping his conversation with the president as part of a plea bargain deal he planned to settle days later. The 38-minute recording was made public, once again turning the country upside down.

In 2014, Brazil’s political and business classes became embroiled in Operation Car Wash, a sprawling corruption investigation that revealed bribes amounting to billions of dollars. Last year, then president Dilma Rousseff was impeached. Now Temer is under investigation by the Brazilian Supreme Court for corruption, criminal organization and obstruction of justice. He is also under huge pressure to resign or face impeachment.

Aside from the question whether Temer committed a crime or not, the taped conversation between himself and Batista exposed how business is done in Brazil, documenting widespread regulatory capture. In the tape, Batista brags about his influence on the media, the judiciary, and the government.

Born into a poor family in the central-west region of Brazil, Joesley Batista, CEO of J&F, the controlling shareholder of JBS, together with his two brothers, built an empire. JBS is the largest private company in Brazil and the second-largest food company in the world. It operates in 150 countries and employs more than 237,000 employees.

Since 2000, the business has grown both organically and through a series of acquisitions. It was preparing to launch an IPO in the United States in 2018 when Operation Car Wash halted its plans. America accounted for 41.8 percent of its business by the time the firm became the target of three different federal police investigations in Brazil. In September 2016, top executives were forced to step down temporarily, amid a probe into fraudulent investments made by pension funds. CEO Wesley Batista was taken in for questioning. In July last year, a unit of the parent company was searched. And in January 2016, a public prosecutor charged executives, including Joesley Batista, of financial crimes.

Batista’s testimony revealed that the company’s exponential growth was based on political connections and campaign donations. He told prosecutors that he had paid off 1,829 politicians and spent some $200 million on bribes in total.

In preparation for the IPO, the company invested heavily in branding, emphasizing the high quality of its product. It hired celebrities in Brazil and carried out massive advertising campaigns across various media. In 2015, JBS became the 15th-biggest advertiser in Brazil, with a total spending of $286 million, according to IBOPE, a market research company. By comparison, its main competitor BRF spent $272 million, which made it the 21st-largest advertiser.

The company’s exponential growth began in 2005, thanks to the support of the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES). JBS received $80 million in loans from BNDES to launch the international expansion that made it a global leader in animal protein. Batista now says he passed 4 percent of this contract on to a third party who helped him get closer to Guido Mantega, president of the BNDES and former finance minister. It was worth it, he said. He says he gave Mantega a Christmas gift worth $5,000 that same year.

In 2007, BNDES bought 12.94 percent of JBS for $580 million and another 12.99 percent for $500 million in 2008. The company changed its name from Friboi to JBS (to make things easier for foreign investors who might have trouble spelling Friboi) and went on a series of acquisitions. It bought Swift, Smithfield Group, and Pilgrim’s Pride. Between 2007 and 2011, BNDESPar, the bank’s investment branch, allocated nearly $2.5 billion to JBS, more than it had ever given to any private group.

At the time, many thought the deal was suspect. It was widely criticized on the basis that it created no direct benefits for Brazil. BNDES’s control of the company increased to 31 percent during that period. Now it is 24.59 percent. The company was the largest donor in the 2014 presidential election campaign, and Batista was offered the privilege of meeting with the finance ministeronce a week, to discuss topics of his interest.

In an interview with the Brazilian daily Folha de S. Paulo earlier this year, Batista said he didn’t know about the extent of corruption in Brazil until Operation Car Wash. “I had no idea about what I have seen on TV. I am perplexed”. Now he says that his business strategy was a way to “gain convenience and avoid the antipathy of politicians”.

On that evening of March 7, when Temer met with Batista at his official residence, JBS was under three separate investigations. Each received a certain amount of attention in the media, but as Batista predicted, the coverage was short-lived. A week later, Operation Weak Flesh hit JBS and the entire meatpacking market, and the same thing happened: intense coverage for a few days, as the Federal Police began to release information about the case, after which media coverage subsided.

Since Brazil is the number one exporter of meat in the world, the story initially received huge headlines in Brazil and internationally. Yet people who are following this story might be surprised to learn that after the first 3 days, this huge story all but disappeared from local newspapers and TV channels in Brazil.

Aside from the sensationalist debate about the quality of Brazilian meat, Operation Weak Flesh revealed a system of corruption involving meatpacking companies and government officials. In 2015, a federal inspector in the Ministry of Agriculture went to the authorities to expose the scheme, which encompassed several Brazilian states. Companies were bribing government inspectors to allow rotten meat to be sold to buyers (including schools) and exported. The inspectors falsified health permits and ignored expiration dates in exchange for money and food products. In order to avoid real inspections, the criminal organization chose which government officials would oversee the companies.

The Brazilian Federal Court accepted charges of 59 suspects under corruption, antitrust crimes and the falsification of food products. Of these, 33 are public officials and 24 are still in preventive detention. On June, 22nd, the U.S. suspended imports of fresh meat from Brazil because of safety concerns.

Large companies, such as JBS and BRF, had employees working inside the Ministry of Agriculture building. They had free access to the inner workings of government and could check inspection procedures, investigations, and data on competitors. The company’s employees produced official certificates and sanitary records themselves, before getting signatures from public officials, who stayed home instead of going to work. Companies require these certificates to sell or export their products. Inspectors went around collecting “weekly or monthly donations” from the companies and plants, which could come in the form of beef, poultry or money—usually all three.

These benefits would be exchanged for campaign donations and personal favors. The companies under investigation, JBS and BRF, donated over $100 million during the 2014 election campaign. The Workers’ Party (PT) and the Brazilian Democratic Party (PMDB) received the most donations, and bribes were paid to Michel Temer’s PMDB.

The agribusiness caucus is one of the largest in Brazil’s Congress, with a total of 207 deputies, out of 513 in Brazil’s lower house. They are a well-organized, powerful bunch: One of JBS’ lobbyists told prosecutors that he had “the largest group of interest in the Congress.”

The Weak Flesh investigation now joins the Car Wash Operation, reopening an even greater process of uncertainty in the country. No one knows where, or to what level, the scandal goes, since it had already reached the highest post in the Republic. When it comes to JBS, what is clear is that everyone had turned a blind eye to the surreal growth of the company at the expense of the government. Until recently, the Batista brothers were considered a model of “self-made men”.

(Note: Alana Rizzo is a director of Abraji, the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism, and a 2017 Stigler Center Journalist in Residence)