New study estimates that the total costs of America’s flawed financial system–rents, misallocation costs, and the costs of the 2008 crisis–will add up to an estimated $22.7 trillion between 1990 and 2023.

Finance and financial markets have been the subject of numerous studies over the last few decades. One reason for that is the huge effect financial activities have on financial markets and the real economy. The other, of course, is the incomparable availability of quality data.

Nevertheless, the number of studies on the effect the financial sector has on society and the economy is more modest, relatively recent, and definitely resulting from the 2008 crisis. One such study, “Overcharged: The High Cost of High Finance,” was recently published by Gerald Epstein and Juan Antonio Montecino from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, as part of a project led by the Roosevelt Institute.((Gerald Epstein and Juan Antonio Montecino, “Overcharged: The High Cost of High Finance,” Roosevelt Institute (2016).))

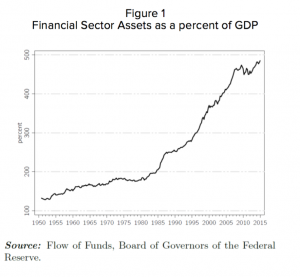

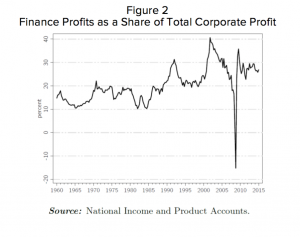

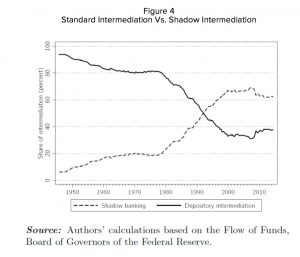

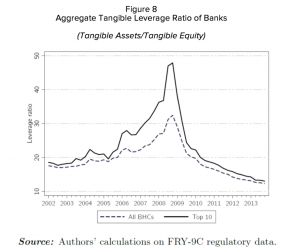

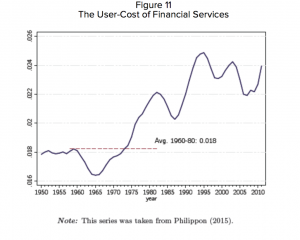

The main premise of their study is that, due to the long wave of financial deregulation, the American financial system increasingly failed at providing its basic functions, and became more involved in the speculative activities that eventually caused the major financial crisis of 2008.

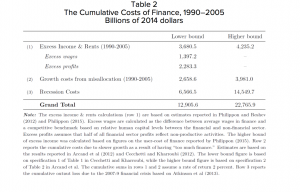

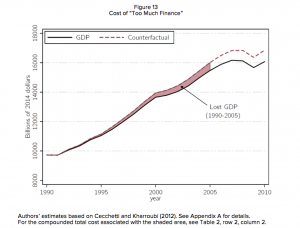

Epstein and Montecino argue that the total cost of the financial system is comprised of rents, misallocation costs, and the costs of the 2008 crisis. Such costs can be divided into two types: transfers and inefficiencies. When combined together, Epstein and Montecino estimate that they total to $688bn a year, or 4 percent of GDP. Cumulatively, from 1990 to 2023, this number would add up to $22.7 trillion.

In an interview with ProMarket, Epstein spoke about rents in the financial system, why the 2008 crisis made the study of inefficiency in the financial system a more accepted area of inquiry, and what role regulation should have in addressing the system’s inefficiencies.

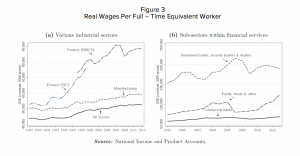

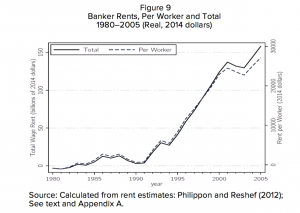

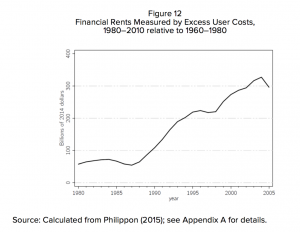

Guy Rolnik: In the paper, you argue that the total cost of the financial system is comprised of rents, misallocation costs, and the costs of the 2008 crisis. Among others, you rely on the work of Thomas Philippon and Ariell Reshef((Thomas Philippon and Ariell Reshef, “Wages and Human Capital in the U.S. Financial Industry: 1909-2006,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 127, no.4 (2012): 1551–1609.)), in order to estimate the total cost of rents in the financial system to be $3.7 trillion. Do you (and the studies you quote) account for the unobservable quality of human resources in the financial industry, compared to the non-financial sectors?

Gerald Epstein: Yes. Philippon and Reshef control for skills, complexity, etc.

GR: Do you account for the unobservable differences in hours worked?

GE: Yes. Please see Philippon and Reshef’s Footnote 42, p. 1594.

GR: Is it adjusted for time? If I am an Investment Banker and I work until midnight, is that time recorded?

GE: It is obviously an estimate based on micro data. These are taken from surveys. I suspect that professionals overestimate their time to convince themselves about how hard they work. But I am not a sociologist who has studied time use data biases.

GR: Is it possible that in finance, the risk associated with loss of jobs is higher?

GE: It is possible. But again, Philippon and Reshef take into account these risk factors in making their estimates of rents.

GR: How do you adjust for risk?

GE: While Philippon and Reshef control for skills, education, complexity, and the differences in hours worked, they did not adjust for risk. Their estimates for risk and some other factors in other parts of the paper reduce their estimates of the rents. The certainty equivalent difference is somewhere between 20 percent and 30 percent. So if this were the correct approach, it would reduce the size of the rents to 2/5-3/5 of the estimates: $558.88-838.2 billion, instead of $1397.2 billion. This is a relatively small reduction ($500 billion to $700 billion) in the overall $12.9 trillion-$22.765 trillion price tag.

GR: Is it possible that in finance, like the petroleum industry, there’s a need

to pay a premium in boom years to attract quality hires?

GE: It is possible, but then they [Philippon and Reshef] are estimating relative wages, compared with other industries that also experience these booms; so that is controlled for. More generally, during this period there is a massive excess supply of workers wanting to go into finance. This is the clearest evidence of rents. I have been teaching economics, including money and banking, at a major state university since 1985. Over that period, with the possible exception of the period during the height of the financial crisis, the large majority of my students wanted to go into finance. There are long lines of people waiting to get hired by the top financial institutions. During this period, these banks did not have a lot of trouble attracting talent. On the contrary: they had more trouble keeping them away. This is a very clear sign of significant rents.

GR: You write that if the financial sector was performing well with respect to the economy as a whole, rent and excess profit creation would constitute a zero-sum process. Is this the problem some scholars refer to as “too much finance?”((Jean-Louis Arcand, Enrico Berkes and Ugo Panizza, “Too Much Finance?” IMF Working Paper No. 12/161 (2012).))

GE: The too much finance literature is a bit of a misnomer (the main authors understand this), because the issue seems also to be, at the margin, what do the least productive, most speculative financial institutions do. Having said that, I do think that various estimates suggest that a productive financial system could be much smaller, perhaps 50 percent smaller. Still, one must be careful and I do think this is an area that requires more research.

GR: In the paper, you review 1990-2005. Why do you stop at 2005, when it is possible that in the years after the crisis profits and compensation decreases?

GE: We stop at 2005 for our rent (and misallocation cost) estimates because that is the last year for which we have the rent data that we need. We are basing one of our rent estimates on the paper by Philippon and Reshef and their estimates end there. It is certainly possible that rents fall after the crisis, at least for several years.

When we add in the cost of the crisis costs using the estimates from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas study, we use their estimates that calculate the longer term costs of the crisis (which seem appropriate), going to 2023, when, using their more conservative estimates, they assume the US economy returns to its full utilization growth path. In adding these (properly discounted) costs to our rents and misallocation cost estimates from 1990-2005, we do not add in any additional rent and misallocation costs that our financial system might impose from 2005 to 2023. In other words, in our total calculation we implicitly assume that there are zero rents (and misallocation costs) from 2005-2023.

In short, we make no explicit claims about the rents after 2005 and, in fact, assume they are zero after 2005. No one assumes the rents are zero after 2005, even if they have come down from the pre-crisis period. So it is a good research study (which we have not done) to look explicitly at rents post-crisis. But we make no explicit claims about that.

GR: You estimate the costs of the 2008 financial crisis as ranging from 40 percent to 90 percent of 2007 GDP: In 2014 dollars, this amounts to $6.6 trillion to $14 trillion over the period between 2008 and 2023. Some would argue that there was a secular recession before the crisis, and that it was masked by the real-estate bubble. Therefore, the recession measured was not all induced by the financial crisis alone.

GE: Yes, this is possible argument, and we address it on page 26. The problem is that there is strong evidence that the expansion prior to crisis was not greater than the average post-war expansion. We drew on evidence from, for example, the Atkinson, et. al., study from the Dallas Fed which was also the basis for the estimates of the crisis costs. On the face of it, as we discuss there, this is surprising. But when you think about the role of finance in increasing inequality over the last several decades, a plausible explanation emerges.

In assessing the cyclical impacts of finance over this period, there are two opposite impacts, and they roughly balance out: 1. If you assume, as is consistent with most studies, that the marginal propensity to consume [mpc] out of income and/or wealth (depending on your model) of the rich is lower than the poor and middle class, then the redistribution to the “1 percent,” which the rise of rent seeking finance helped to generate, created a dampening cyclical effect on the economy (due to the lower mpc of the rich). So, by itself, this would have lowered the growth over the pre-crisis bubble period.

On the other hand, finance did create a bubble so [there was] an increase in short-term apparent wealth which would have led to an increase in consumption.

So, it appears, on balance, the two opposite cyclical impacts balanced each other out, so the net cyclical effects of finance during this period (prior to the crash) were approximately zero. So that is why we did not add in a net positive impact for finance for this period.

Of course, this is just a plausible conjecture. To really establish this would require another study. It would make, for example, a good dissertation chapter or something like that. But I think it is just as plausible as the opposite argument.

GE: In my view, this is highly implausible. The big difference in the speed of the recovery lies in the very aggressive monetary, LOLR [lender of last resort], and fiscal policies of the Fed and the government (as well as the IMF and other countries) after the [global financial crisis] of 2008, as compared to the 1930s).((On the limited Fed policies during the early 1930’s, see for example, Gerald Epstein and Thomas Ferguson, “Monetary Policy, Loan Liquidation and Industrial Conflict: The Federal Reserve and the Open Market Operations of 1932,” Journal of Economic History 44, no. 4 (1984).))

GR: How much intellectual energy has been devoted in the last decade to estimating the amount of rent seeking, inefficiencies, and bloat in the system?

GE: Prior to the financial crisis, there was almost no work in terms of making quantitative estimates. There were centers of serious research discussing the problems and inefficiency in finance, but these were mainly considered to be ‘outside the mainstream’ and were largely ignored. These and other critical voices were pretty much ignored, and this is certainly due to cognitive capture as well as other types of capture–see my paper in the Cambridge Journal of Economics.((Jessica Carrick-Hagenbarth and Gerald A. Epstein, “Dangerous interconnectedness: economists’ conflicts of interest, ideology and financial crisis,” Cambridge Journal of Economics Volume 36, no.1(2011): 43-63.))

However, after the crisis hit, then this capture was busted open a little bit and then more people started looking at this—not just me and my students, but economists from the BIS, the IMF, and elsewhere. So this is now a more accepted area of inquiry. The cognition has now staged a jail break; we will see if it gets put back in a cage soon.

GR: Is the IRA, 401K pension system efficient? Or is it much too bloated and non-competitive, thus creating hundreds of billions of dollars in annual costs (asset management and advisory) that do not create better allocation of resources?

GE: Yes. Our paper has a section on asset management where, building on others’ research, we show the very significant amounts of incomes generated in the asset management sector (Greenwood and Scharfstein make this point as well). We go through various estimates by John Bogle and others that indicate that actively managed portfolios, for example, have more than 2 percentage points lower net returns relative to index funds (4.73 percent vs. 6.94 percent), which is almost 50 percent lower (see our table 7 on p. 34). We also have a section on private equity and hedge funds which surveys evidence that these can lead to excessive short-term orientation, and asset stripping from productive businesses (in the case of some PE firms).

GR: Given the asymmetric nature in many activities of finance, do we need more government nudging to decrease costs?

GE: Yes, at the minimum. We very briefly outline more significant reforms at the end of our report. But in terms of nudging, implementing more serious fiduciary responsibility rules and more transparency in information about risks and returns are a minimum. In terms of really shrinking the unproductive size and nature of the financial sector, however, I think much more than simply nudging will be required. It is interesting that the platforms of both major parties now say something about limiting the size and riskiness of the large banks, for example. But these are very big issues and require careful discussion.

GR: Can we estimate how much talent the financial system sucked out of science, health, medicine and other disciplines, due to its size and higher compensation?

GE: Excellent question. This is a very good research project. I have not seen the numbers other than anecdotal evidence about this. But I would think this is a very fruitful area for future research.

GR: Should we have a target number to reduce the size of the financial system as percentage of GDP?

GE: I do think we need to reduce the size and change the nature of finance. But as I suggested, it would be too simplistic to think we could come up with a particular number or even a really narrow range.