Bo Rothstein, one of the most influential political scientists in the world today, explains how countries can become less corrupt, and why the Nordic model is successful. The first of a two-part interview.

Bo Rothstein, a Swedish political scientist who recently moved from the University of Gothenburg to the Blavatnik School of Government in Oxford, has been studying the Nordic model, corruption, and governments for decades. Unlike many of his colleagues, he has little interest in politics, voting, parties, or philosophy. He is a much more pragmatic guy. His research focuses on the quality of government—what is the outcome of governments’ work((Rothstein, Bo. 2009. “Preventing Markets from Self-Destruction. The Quality of Government Factor.” University of Gothenburg, QoG Working Paper series 2009:2)). Rothstein’s interest in quality of government led him to address questions regarding the role of corruption ((Persson, Anna, Bo Rothstein, and Jan Teorell. 2013. “Why Anticorruption Reforms Fails: Systemic Corruption as a Collective Action Problem.” Governance, an International Journal of Policy Administration and Institutions 26; pp 449-471))and quality of life, how countries become less corrupt((Rothstein, Bo. 2007. “Anti corruption: A Big Bang Theory.” Göteborg University, QoG Working Paper series 2007:3)), and how taxpayers perceive those issues((Rothstein, Bo. 2013. “Corruption and Social Trust: Why the Fish Rots From the Head Down.” Social Research vol. 80, no. 4)).

Rothstein, who was a visiting professor at the Stigler Center earlier this year, is one of the world’s foremost political scientists. Before moving to Oxford, he held the August Röhss Chair in Political Science at the University of Gothenburg and co-founded the university’s Quality of Government Institute, which deals with “the theoretical and empirical problem of how political institutions of high quality can be created and maintained.” His perspective is rooted in his perch in Sweden and his research on Nordic countries and welfare states((Rothstein, Bo, Marcus Samanni and Jan Teorell. 2011. “Explaining the Welfare State. Power Resources versus the Quality of Government.” European Political Science Review, Volume 4, Issue 01; pp. 1-28)). In The Quality of Government (University of Chicago Press, 2011), he explored the role strong institutions play in the function of competitive market economies, and argued that impartiality is a crucial requisite for quality government.

Sweden and Denmark are two of the most interesting cases in the world in terms of economic policy. Although they are usually known as “social democracies”—a term that has been used very often since the appearance of Bernie Sanders in the presidential race—they differ very much from the stereotype.

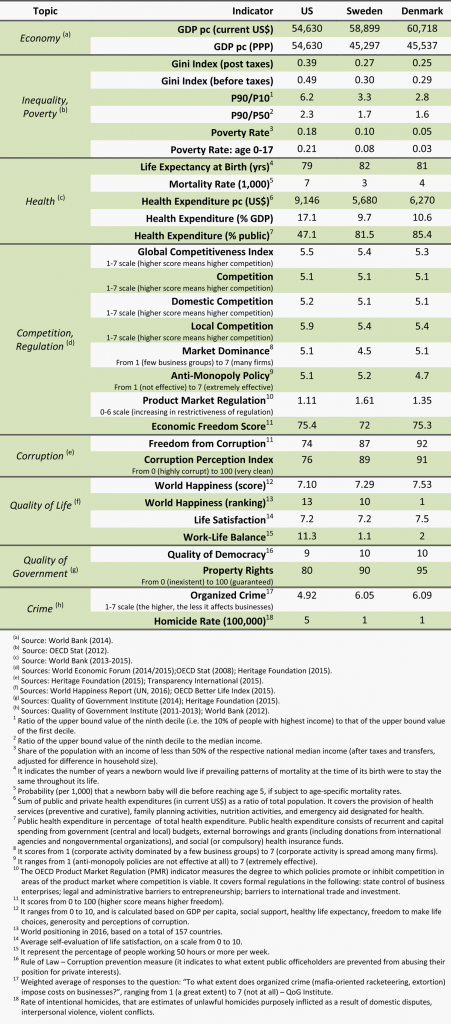

In the last few decades, Sweden and Denmark have adopted pro-market and pro-competition policies; Denmark has one of the most flexible labor markets in the world((Andersen, Torben M.; Svarer, Michael. 2007. “Flexicurity: labour market performance in Denmark.” CESifo working paper, No. 2108)) and Sweden Privatized and outsourced many government activities. The Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, ranked Denmark above the U.S. in its 2014 index of economic freedom. In the table below we can see that the two small countries fare very well compared to the U.S. in most parameters:

While Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump promise their supporters to protect local manufacturing industries from international competition, Denmark and Sweden do the opposite: both countries are open to competition and are rated above the U.S. in trade freedom.

The Scandinavian countries’ abilities to have high quality of life, high growth, low inequality, and high taxes is often attributed to their culture and homogeneity. Nobel laureate Kenneth Arrow famously said((Arrow, Kenneth. 1972. Gifts and Exchanges, Philosophy and Public Affairs, (1), pp. 343-362.)) that: “Virtually every commercial transaction has within itself an element of trust… It can be plausibly argued that much of the economic backwardness in the world can be explained by the lack of mutual confidence.”

Swe

den, Denmark, Finland, and Norway are a case in point: according to surveys like the European Commission’s Eurobarometer, they lead the world in the level of trust. Rothstein attributes it to the quality of their government.((Rothstein, Bo, Persson, Anna. 2015. “It’s My Money: Why Big Government May Be Good Government.” Volume 47, Number 2; pp. 231-249))

Big investments – still no water

Rothstein started his career by asking why some countries have more generous welfare policies than others. Yet he did not actually look at how people receive welfare. He studied the way in which states interact with large interest organizations. He looked at why policies were enacted but not whether they actually had an effect.

|

His decision to start looking at the way policies are enacted started in Africa by accident: “Some 15 years ago, I had a PhD student who was studying water management in African countries. This person put me in contact with colleagues from the technical universities who study water, hydrogeologists. They had some very disturbing things to tell.

“First, at about that time, and I think it’s the same now, some 15,000 people died every day in the world because of lack of access to safe water and sanitation. Then they said, ‘This is not because there is a lack of natural water. This doesn’t explain anything, hardly, of the problem.’

“Then they said,‘We are engineers. We are from technical schools. We convinced the international aid and development community over the last 50 years to invest in all kinds of technical equipment in these countries: sewages, water cleaning stations, canals, pumps, whatever it is.

“‘But these don’t help much, for two reasons. First, the procurement systems in these countries are usually so corrupt, so the machinery simply falls apart after a few years.

“‘Secondly,’ they said, ‘people usually refuse to pay for the water because they think that the money will be stolen. So the few people in charge who are honest and really want to keep their systems running, never have enough resources to do so.’

“They told me, ‘Well, this is not really physical infrastructure, this is actually a political science or a public administration issue. The problem is basically a problem of corruption. We have to correct it.’ “This was an argument I couldn’t refuse. Most of my colleagues are interested in the political game: who wins elections, who becomes president, how parties are formed, how international negotiations are handled, and so on.”

“This is fine, but I decided I wanted to have human well‑being as my dependent variable: what the state actually can do and should do in order to improve human well-being, not politics. I’m not so interested in explaining politics, actually.”

The belly of the beast

Guy: Would you agree that many political scientists focus on institutions: they look at the rules, the laws, the constitution, and the formalities? Very little research is done on what’s really happening in the “belly of the beast,” how it really works.

Bo: Yes. This is maybe what also differentiates me from most of my colleagues. I think about politics from the output side, from the administrative capacity of the state, not so much from the input side—behavior, opinions, political mobilization. I’ve always been very interested in the administrative side of things, how things are actually done.

The other thing is that, and this also goes back to an argument from Douglass North that we tend to focus far too much on formal institutions while, he argues, we should also pay much more attention to informal institutions.

That is one reason I became very interested in social trust. Basically, social trust, or distrust, is an informal institution in society. You can say this has to do with cultural studies, but I tend to think of informal institutions not as cultures but what you can call “standard operating procedures.”

Take an academic seminar as an example. Different institutions have different standard operating procedures regarding how seminars should be run. Everyone knows them, but they’re not written down. For example, there is no document that says that, in all seminars, we let the speaker speak and then we have questions.

In other seminars, we think it’s good to constantly have the questions and have a dialogue, or interruptions. None of this is written down. This is, of course, an informal institution.

The problem with free elections

G: Would it be accurate to say that you’re more interested in the outputs of democracy, of political institutions, of government, than in the input? Most political scientists look at the inputs: voters, parties, opinions. You are saying, “If we really want to understand what happens, input won’t help you a lot. Let’s focus on the output.”

B: Yes. I can give you an example. Free and fair elections are generally thought to be the big thing—we should have countries introduce free and fair elections.

The problem with free and fair elections is that organizing them is a huge administrative and very complicated task. Countries that have very low administrative capacity, which also usually have high levels of corruption, cannot organize free and fair elections.

Everything will be tainted, and hence the elections won’t have legitimacy. If you don’t have reasonably high administrative capacity, you cannot have free and fair elections. Or, if you have the

m, their results will be good for nothing.

Take the West—and this is an argument from Francis Fukuyama—the West thought if we had elections in Iraq and Afghanistan, things would go well. Well they didn’t. The reason is this huge lack of state capacity, or what I call quality of government. A parliament can make many decisions, but if it doesn’t have the administrative capacity to make sure they are implemented, nothing will happen. People will be very disappointed with democracy.

Think about it: healthcare, universal education, infrastructure, social insurance, immunization—all these involve huge administrative undertakings. In order to implement these, you have to have quite high administrative capacity. You can say the state doesn’t need to do it itself—it can hire contractors. But monitoring contractors is, in itself, a complex task that you cannot perform if you don’t have the capacity and competence.

Think about it: healthcare, universal education, infrastructure, social insurance, immunization—all these involve huge administrative undertakings. In order to implement these, you have to have quite high administrative capacity. You can say the state doesn’t need to do it itself—it can hire contractors. But monitoring contractors is, in itself, a complex task that you cannot perform if you don’t have the capacity and competence.

People don’t experience public policy by reading the law; they experience public policy by meeting the healthcare professionals, the people helping them in the social insurance institutions, and the public school teachers.

G: Political scientists and economists have a lot of data on voting and parties at their disposal and therefore many research opportunities. Yet maybe the important processes are taking place in a less transparent part of society.

B: I’m not saying that voting and government decisions are unimportant, but they are not as important as many of my colleagues would think. There are a number of other things that are important.

First, there are strong, organized interest groups. Take, for example, education: teachers’ unions play a big role. The same holds for agriculture and healthcare.

Then you have professional norms that are established by universities, experts, and trade organizations. Then there are, of course, all kinds of things that shouldn’t have an influence in many developing countries: public sector corruption, bribes, and nepotism. And not only in developing countries.

G: How important is the study of special interest groups to quality government?

B: Policy in most countries is hugely influenced by other things than the will of the people. It’s influenced, as you say, by organized interests, by special interest groups, and by professional groups. Some of this is probably bad. Some can be good, because it feeds the system with a lot of competence.

These groups know a lot. Of course, they don’t use their lobbyists just for the public good. They have their own interest. Some democracies are good at not falling for what economists would call endemic rent-seeking from these groups. Some democracies seem to fall prey to special interest groups in a way that is very problematic.

Importing integrity

G: When we look at the power of information and expertise and think about the relations between the regulators and the industry, can we be tempted to conclude that the concentrated interest will almost always carry the day?

B: It can be, but I don’t think this is a social science law. First, some states are quite good at using independent expertise. They create expert commissions and public investigations where they ask the best researchers and policy-oriented researchers to participate.

They have ways of feeding the system with knowledge that is not systematically biased. Secondly, some states are quite good at recruiting competent people to the civil service. They care very much about getting the best and the brightest to actually work in the government. They pay them well. There, high-level civil servants enjoy a high status.

I’m not arguing for a rule by experts. At the end of the day, the elected politicians should have the final say. But I’m very much in favor of what you can call rule through experts. The state can, in various ways, create a passageway for information that is completely untainted by special interests.

G: Only a handful of states can do that.

B: It’s not many. If they don’t have enough, they can call in international experts. In some cases, all the local experts are hired by, say, the local healthcare industry and you need to reach out abroad. For example, a small country like Sweden, all the experts come from outside Sweden.

G: In a market economy, a big part of the role of the state is not only to provide public goods but to regulate markets. One of the outcomes of market economies is a growing pay gap and, specifically, large pay difference between regulators and the top talented people in the regulated industries. Finance is a good example. This may create a structural problem of “revolving doors” when pay in the private sectors is dramatically higher than for top people in regulatory agency.

B: You may very well be right. I think that increasing inequality is a problem. However, my normative preference is not necessarily a more equal society. My normative preference is a society where you have quite a high threshold under which nobody can fall.

You cannot allow people to be destitute. You take care of them. Then, I think, the sky should be the limit. I would like to have a society that looks like this. Above this level, I don’t care so much if people make tons of money, as long as they made it in a reasonably honest way, with talent and competence.

Secondly, yes, many people, for them, money is the most important thing. But you have lots of people for whom it’s not. There are actually very talented students that go to study art, or become librarians or social workers or maybe study political science.

They know that they are very smart. If they went into business, they could earn much more money, but they don’t. There are other things than money that seem to be very important, not least to young people. Business schools are full, but there are many other schools that are doing quite well. And people go there. They are very smart. They could easily go to business school or to medical school but they choose not to.

Secondly, this is maybe a personal experience, you can get to situations where nothing that costs money would improve your life. Nothing. At least, I experienced that a number of years ago in my life.

G: That’s because you are from Sweden, where the culture is different.

B: No, it’s because I live a reasonably nice, comfortable, middle‑class life. I wouldn’t be one cent happier if I could buy a new Mercedes, a bigger sailboat or a phenomenally more expensive wine. It wouldn’t improve my life. What improves my life is other things than money.

For many people, especially if you go into academia, it’s the esteem of your respected colleagues that counts.

G: This is a good point, because many times the way special interest groups capture politicians, regulators, and experts from those academic institutions is by using reputation mechanisms. There are subtle, more complicated ways that special interest groups can influence the prestige and reputation of the experts. We see them using funding of research and conferences to influence the reputation of experts.

B: It’s not so easy. They can try, but if we would find out that we have colleagues whose research is tainted because they were funded by special interests, it would be like a death sentence. They won’t survive. But, I see your point. It’s, of course, a problem. This problem exists in the pharmaceutical industry. I may be a romantic, but that is why I have been a strong defender of academic freedom. I think a society needs to be balanced.

B: It’s not so easy. They can try, but if we would find out that we have colleagues whose research is tainted because they were funded by special interests, it would be like a death sentence. They won’t survive. But, I see your point. It’s, of course, a problem. This problem exists in the pharmaceutical industry. I may be a romantic, but that is why I have been a strong defender of academic freedom. I think a society needs to be balanced.

I’m a big fan of markets. Markets can be very good, but they have to be balanced by things that are not markets, like the rule of law, independent research, freedom of the press. If you “marketize” everything, it will go astray.

G: Let’s look at informal activities—institutions that foster a culture of integrity and professionalism in a regulatory agency. Can you describe them?

B: This is a very hard question. The natural, or maybe I should say biological, instinct is, if you have a position of power, to use it for yourself, your friends, your family, your clan, your tribe, your political faction. You will be partisan, right?

Not being that has to be a trained thing. You have to somehow, by professional norms and ethics, have to realize that you will not be respected by your peers if you do not live up to the norms of unobtrusiveness and impartiality. You will be systematically biased, and that will not be respected.

I use a metaphor from sports. Many people go to games. They cheer their favorite team. I ask them, “Why are you not cheering the referees?” They look at you like you’re an idiot.

Then I say, “You know that without at least a few impartial referees on the field the game will have no value. The league will collapse.” If the one team thinks that the other team paid off the referees, they will just go home or they will also try to bribe the referees.

If you look in a soccer field, there are 22 players and three or four referees. That’s why it works. The referees are not perfect. They make mistakes. Sometimes, they favor the home team a little bit.

But it evens out. But if we found out that there were referees who actually were paid under the table, or that were die‑hard supporters of one of the teams, we wouldn’t accept it. This is the mechanism that is my favorite.

You can think of the teams as players in the market. They want to win. They do everything to win, but if they pass this threshold and start bribing or buying off the referees, the whole market will collapse. That is why I’m saying that my favorite expression is that you can have a market about everything, as long as you don’t have a market for anything.

If the referees are for sale, the league, which is the market here, will collapse.

The logic of appropriateness

G: The referee example is great, and it leads to my next question. A football game, at the end of the day, is pretty simple: most fans know the rules, they follow the game, and their eyes are focused on the ball.

In regulation and public administration, the job is not only dramatically more complicated, but most of it is not visible to the taxpayers. Reputation is a great tool for markets, but many politicians and regulators chose courses of action that increase reputation and not necessarily the best outcomes.

B: No system is perfect. All the good things that you mentioned exist, but because there is a reasonable number of bad apples, not all the apples need to be bad. That’s how I think, and this is a struggle. This is why I teach students about this. It is very important that they learn this distinction between having one rule when you are in the market and another rule when you are taking care of public good services.

I will give you an example. If I am a judge, nobody would say I’m doing anything wrong when I’m selling my house and I try to get the highest price I can. That’s perfectly OK. Nobody would think I’m doing something wrong when I’m at home and take special care of my kids or my friends and family. That’s also OK.

Nobody would think that I’m doing something wrong if I’m a member of, say, an environmental protection organization. I have the right to do this. But everyone would think I was doing something wrong if my verdicts, seating as a judge, could be bought.

Now I’m wearing this hat, and now I’m wearing the other hat. It has been called the logic of appropriateness. Your behavior may be acceptable in a certain setting, but when you cross the line, that threshold, this behavior is completely unacceptable in the new setting.

It’s understanding which of these settings you are in when you act. If I’m a judge, and my son is taken into the court, I should say, “No, I cannot. I should stay away.” This is a natural thing to do. In a corrupt system, you would say, “No, I know him best. I should be the judge of him.” That’s not how we think about it.

(Note: This is the first of a two-part interview with Bo Rothstein. The second part can be read here)