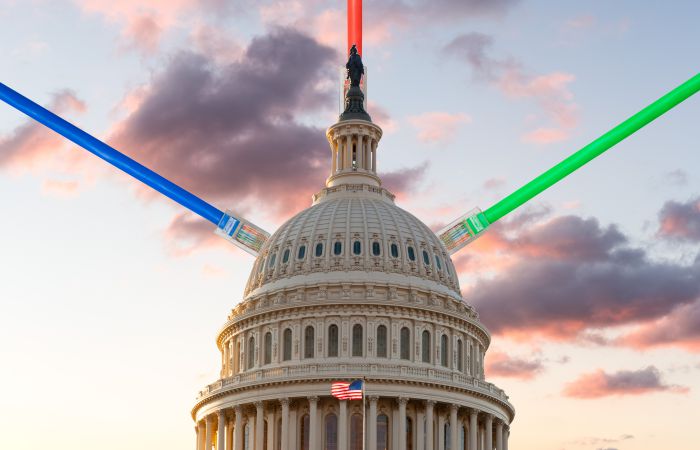

Every promise made by broadband providers and every reason cited by the FCC in its decision to eliminate the net neutrality rules has proven false in the past year, writes Gigi Sohn. Nevertheless, there is cause for optimism: “There will be net neutrality in this country within the next several years.”

Today (December 14th) is the one-year anniversary of the FCC’s decision to repeal the net neutrality rules that had been in place since 2015. During the past year, there hasn’t been even one reason underlying that decision that has come true. In fact, the opposite is the case.

Prior to the net neutrality repeal, broadband providers argued that they would deploy their networks to more people, especially in underserved areas, that prices were going to go down and that there would be no blocking, no throttling, and no discrimination against or in favor of any particular Internet traffic.

The latter, in particular, turned out to be false: In September, researchers at Northeastern University and the University of Massachusetts Amherst published a study showing that all four mobile carriers throttle video services like Netflix and YouTube for no particular reason, other than, perhaps, to force consumers to a more expensive tier of service. The repeal of net neutrality has directly helped a company like AT&T, which now has DirectTV and the Time Warner properties, to favor its own video services and content. As 4K video becomes more prevalent, this is going to happen more and more. As long as your broadband provider tells you that this is what they’re going to do, you don’t really have any recourse.

Broadband companies also claimed that they would invest more in their networks once the burden of net neutrality regulations were lifted. Yet both Charter and Verizon recently said that they’re going to invest less. Why is that? Because investment has little if anything to do with regulation. It has to do with the level of competition, with the economic environment, taxes, and other factors. FCC Chairman Ajit Pai recently publicly praised a report by USTelecom, the broadband industry’s trade group, that showed investment skyrocketed between 2015 and 2017. Well, guess what? That’s when net neutrality rules were in place, since the repeal didn’t become effective until the second of half of 2018. All that goes to show that net neutrality wasn’t bad for investment, as broadband providers claimed.

Not telling the truth, of course, is not necessarily the province of only cable and broadband companies, but those companies have a particular history of making many promises they don’t keep. However, this is a two-way street: Broadband companies may not keep their promises, but it’s the regulators that don’t hold them to account.

Which is what’s most significant about the net neutrality repeal: In its decision to eliminate the 2015 rules, the FCC made it clear that it was abdicating its role protecting consumers and competition, leaving consumers who believe that they’ve been subjected to a net neutrality violation with nowhere to go.

A good example of this is what happened to the Santa Clara County fire department which, as firefighters were battling the Mendocino Complex fire in August—the largest fire in California’s history at the time—had its broadband throttled by Verizon. The fire department was forced to negotiate with Verizon for eight months before it finally decided to give up and pay more than double what it was paying Verizon before. That was because there was no agency it could go to that would hold Verizon accountable. What was most telling about this was that while the story became national news, I didn’t see one statement either from the FTC or the FCC saying, “If you’d only called us, if you only filed a complaint, we could’ve taken care of it.” So when your broadband provider decides one day to triple the price for your broadband service, who are you going to call? Nobody. Short of lying about the services they deliver, broadband providers can basically do whatever they want.

Moreover, as the recent federal attempts to stop California and Vermont from enforcing their own net neutrality laws show, even when the federal government abdicates its regulatory authority, it tells the states that they can’t protect consumers either. Having washed its hands of its regulatory responsibilities, the FCC is now turning around and, with the full power of the White House behind it, telling states they can’t step in to fill the void. What’s incredible about the Vermont case is that broadband providers are saying that Vermont doesn’t even have the ability to decide whether the broadband providers that the government contracts with should abide by the 2015 net neutrality rules. That, to me, is even more outrageous.

The irony here is that when we tried to preempt states from blocking municipal broadband from being built while I was at the FCC— there are about 19 states that have laws against municipal broadband systems either being built or expanding—Chairman Pai opposed it. And yet his FCC has preempted states and localities from making their own decisions about where 5G antennas are placed. There’s absolutely no consistency here. The only consistent thread that binds together Chairman Pai’s decisions is that they all help the largest broadband providers.

Over the past year, we’ve also seen that the abdication of accountability and of authority by the FCC trickles down into issues that go beyond the blocking or throttling of content. The rural broadband digital divide, for instance, is not getting resolved, and that is a failure of the FCC and the federal government not providing adequate resources.

All this is why when people talk about future net neutrality legislation, I remind them that the fight really isn’t over the blocking/throttling/paid prioritization so much as it is over whether there will be accountability, whether there will be an agency with the authority to look at these instances and determine whether or not they are anti-consumer or anticompetitive. If Congress adopts rules but doesn’t give the FCC the authority to enforce them, they’re not worth a damn.

I’m optimistic, because Americans are overwhelmingly in favor of net neutrality. Every poll that’s been done by both conservative, liberal, and neutral pollsters has shown 85 percent support for net neutrality. While opponents of net neutrality argue that people don’t really understand what net neutrality is when they respond to such polls, recent polls have been very, very specific. At a certain point it becomes very, very hard to ignore that kind of sentiment.

For this reason, I think there will be net neutrality rules in this country within the next several years. The question is how it will be reinstated: whether through a court decision, Congressional action, or through elections followed by a new FCC. There’s a case challenging the repeal of net neutrality in the courts that will be argued on February 1st, and if supporters of net neutrality win that case, the FCC will have to reinstate the 2015 rules along with the authority on which they were based.

Another way to reinstate net neutrality is for Congress to act. Despite some differences, there’s an overall consensus among Democratic and Republican legislators that blocking, throttling, and paid prioritization are bad. The fight is going to be over authority and accountability—or, to put it more accurately: over who enforces the rules.

While net neutrality won’t be a priority for Republicans, it will no doubt be high on the agenda for Democrats heading into 2020, with every single Democrat running for the party’s nomination in 2020 likely to pledge to reinstate the rules if elected.

There are those who say that people are sick of net neutrality and that they have moved on, but I don’t see that happening. As somebody who’s been doing this work for 30 years, it amazes me how net neutrality has become a national issue. Americans understand that broadband is critically important to full participation in society, in civic life, in the economy and in the culture. And they are tired of the lack of competition and high prices for broadband, if they can get broadband at all. Most of all, they want to control their Internet experience, and they know that the only way to guarantee this is for net neutrality to be reinstated.

Gigi Sohn is a distinguished fellow at the Georgetown Law Institute for Technology Law & Policy, a Benton Senior Fellow and a former counselor to then FCC chairman Tom Wheeler. She is also the co-Founder and former CEO of Public Knowledge.

Disclaimer: The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.