As more and more lobbyists move to consulting and PR agencies, experts say the underworld of hidden lobbying is probably much bigger than what formal disclosures and registries reveal.

This is the second part of a two-part series on hidden lobbying. You can read the first part here.

In February, former top Obama aide and Uber executive David Plouffe was handed a $90,000 fine by the Chicago Board of Ethics after a local watchdog revealed that he lobbied Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel on behalf of Uber without registering as a lobbyist—the largest fine ever imposed by the Chicago Board of Ethics.

Plouffe’s case is not unique, in the sense that many people who are actually engaged in lobbying do not register as such. In Plouffe’s case, it was a clear breach of a duty, but in many other cases, no laws are broken.

One such prominent case is that of former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich. After leaving Congress, Gingrich founded a consulting firm that engaged in what many—including at least one fellow top republican: Mitt Romney—considered lobbying, despite never having registered as a lobbying firm.

How big is the “hidden” lobbying phenomenon? Interviews with lobbyists and lobbying experts paint a very clear picture: The lobbying underworld is probably bigger than what formal disclosures and registries suggest.

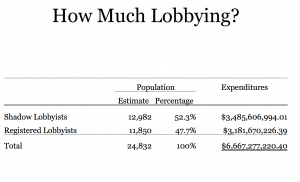

In 2013, Tim LaPira of James Madison University and Herschel Thomas from the University of Texas at Austin tried to estimate the size of the hidden lobbying phenomenon in their paper “Just How Many Newt Gingrich’s Are There on K Street? Estimating the True Size and Shape of Washington’s Revolving Door.” LaPira was (among other things) a researcher at the Center for Responsive Politics, where he was responsible for creating the lobbying and campaign contribution database OpenSecrets.org.

The definition of “lobbyist,” as found in the Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995 (LDA), is narrow enough to allow many people who are actively engaged in lobbying to not register as such. The law states: “The term ‘lobbyist’ means any individual who is employed or retained by a client for financial or other compensation for services that include more than one lobbying contact, other than an individual whose lobbying activities constitute less than 20 percent of the time engaged in the services provided by such individual to that client over a 3-month period.” Only those who meet all three criteria are obligated to register.

The major loophole here is “20 percent of the time,” since lobbyists tend to have many clients, with none occupying 20 percent of their time.((Even considering the narrow definition, a March 2016 report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO)—which, as in its previous reports, painted a positive picture—stated that “As in our other reports, some lobbyists were still unclear about the need to disclose certain covered positions, such as paid congressional internships or certain executive agency positions. GAO estimates that 21 percent of all [lobbying disclosure] reports may not have properly disclosed one or more previously-held covered positions.”))

The practice of dodging registration is known as the “Daschle exemption,” named after former Senate Majority leader Tom Daschle, who became a “special policy adviser” to a leading Washington Law firm, Alston & Bird, in 2005. (Daschle officially registered as a lobbyist in 2016.)

In trying to estimate how many “under-the-radar,” “stealth,” or “shadow” lobbyists exist, LaPira and Thomas used what they called “the lobbyist phonebook,” a directory called lobbyists.info that advertises itself as “your one-stop resource for information on lobbying and government relations inside the Beltway and across the nation.” They then drew a random sample of registered lobbyists and unregistered policy advocates and checked where they used to work and what they do now.

After setting a definition for lobbying, or “policy advocacy”—people in the private sector getting paid to influence public policy, regardless of the strict definition of “lobbyist” in the LDA—LaPira and Thomas found that 52 percent of those involved in this type of activity did not report activities related to lobbying in the year they surveyed (2012). This also means that, since in 2012 about $3.3 billion were spent on lobbyists registered under the LDA provisions, the total amount spent was probably double that sum.

LaPira and Thomas stress that this estimate is based on broad assumptions and are therefore cautious. Nevertheless, they are convinced that “In all likelihood, the political economy of policy influence is much larger than our estimates here.”

Dividing their estimate of total lobbying expenditures ($6.7 billion) by the number of members of Congress (535), they found that the influence industry produced about $12.5 million in revenues per each member of Congress for 2012 (an election year)—almost 10 times as much as that year’s average budget for a member of the House of Representatives, which was $1.3 million. LaPira and Thomas also wrote that their $6.7 billion estimate was about $500 million higher than all of 2012’s campaigns.

In a conversation with ProMarket, LaPira says that the real size of the lobbying market is “probably even way more” than the registered, reported amount. “It’s easy as an outsider like me,” he says, “to attach a really broad definition of what we mean by lobbying and advocacy. The broader the definition, the more people you capture with the net. It could be significantly more, and it could be three or four times as large.”

Former health insurance industry executive Wendell Potter, previously the Vice President of Corporate Communications at health insurance company Cigna, agrees that the estimates in LaPira and Thomas’ paper may have been too low.

Potter, who quit the insurance industry and became a consumer advocate, described in his book Deadly Spin: An Insurance Company Insider Speaks Out on How Corporate PR Is Killing Health Care and Deceiving Americans (Bloomsbury Press, 2010) the way in which companies such as the one he worked for use intentionally misleading tactics to achieve favorable regulation.

“I think [LaPira and Thomas’ numbers] are probably underestimated,” says Potter. “I think that much of the influence is not by direct lobbying, or at least by those people who actually register as lobbyists. At the same time, much of the money that is being spent by big special interest groups isn’t reported in any way. It’s done through PR firms and advertising firms to influence public opinion to influence public policy to influence lawmakers.”

Who doesn’t disclose?

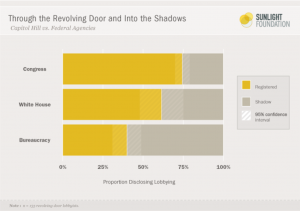

In attempt to characterize individuals who engage in lobbying without registering, LaPira and Thomas divided registered and non-registered “shadow lobbyists” into two groups: the “revolvers”—those who held positions in the federal government—and those who had never held such positions.

The result was that a majority of the registered lobbyists (59 percent) and a minority of shadow lobbyists were revolvers. Within the shadow lobbyists, LaPira and Thomas found, those who never worked for the government are more likely to not register.

Why are revolvers more transparent? To answer that question, the researchers drilled deeper into their sample and divided the revolvers into three groups representing the branches in which they were employed—Congress, the White House, and the bureaucracy—and then checked how many were registered and how many were shadow lobbyists.

LaPira and Thomas found that the likelihood that revolvers would register was highest if they worked in Congress, followed by lobbyists who worked in the White House. The likelihood that revolvers who worked in the bureaucracy would register was the lowest.

“It’s ‘lobbying’ if lobbyists are lobbying on Dodd-Frank when it was just a bill in Congress, but it’s ‘not lobbying’ if lobbyists are lobbying on Dodd-Frank when it is a proposed regulation at the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. Or the Treasury Department. Or the SEC. Or the FDIC. Or the Fed. Or, if they’re lobbying on the thousands of other regulations proposed by federal agencies every year,” LaPira and Thomas wrote.

Taking into consideration the stigma of lobbying and the apparent narrow definition of lobbying within the LDA, LaPira and Thomas conclude that the LDA resulted in less, not more, transparency.

Even when considering registered lobbyists only, a puzzling phenomenon appears: according to OpenSecrets.org, between 2007 and 2016, the number of lobbyists declined by almost a quarter—from 14,822 to 11,143. During the same time, total spending on lobbying increased by almost 9 percent.

Taking these numbers at face value, they seem to suggest that the number of lobbyists fell, and that, at the same time, spending per lobbyist rose sharply—by almost 45 percent—which does not correlate with less lobbying.

The reason that registration fell is the 2007 Honest Leadership and Open Government Act (HLOGA), which came into effect in 2008. The Act was a reaction to the Jack Abramoff scandal, in which Abramoff, a former lobbyist, was convicted in 2006 of conspiracy and wire fraud related to his lobbying work and eventually served 43 months in prison.

After being released from jail, Abramoff wrote a book that provided an insider’s look at lobbying. In numerous interviews, he exposed the ways in which he and his friends in the lobbying industry bought and sold legislation.

The HLOGA added restrictions to the LDA, but many experts believe that did not contribute much to the transparency of lobbying in Washington—rather, it drove many of the lobbyists to go underground.

LaPira quotes a lawyer who explained to him how the HLOGA encouraged lobbyists to avoid registering: “Prior to HLOGA—and prior to the Obama administration—I would say that most of us in town who advise clients erred on the side of telling them to register [under the LDA]. There wasn’t much of a struggle with ‘Is this 20 percent or not?’”

In the conversation with ProMarket, LaPira shed more light on the dynamics set in motion by HLOGA: “The law is probably one of many factors that are causing what seems to be a declin

e in lobbying in Washington, or what appears to be a decline. I think it was a trigger.”

He added: “There are some other things, of course. Congress is doing fewer things, there’s less of an incentive for corporations and associations to pay lobbyists, the Great Recession in 2008 and 2009, there’s less money available for lobbying as an expenditure, and so forth and so on. There’s a lot of things going on here.

“2007 was a trigger because before [HLOGA], the statutory definition was the same, but there was very little downside for any lobbyist to report or register their activity. They didn’t face any liability. After it became law, in 2008, many political law and compliance attorneys started recommending to their clients: ‘You might want to think twice about calculating your time.’ The new law included additional reporting requirements for campaign finance activities and also subjected them to audits by the government. These were new risks that the law created that didn’t exist prior to that, that essentially created a disincentive to report their lobbying activities,” says LaPira.

Abramoff, who has become a stern, vocal, and persistent critic of the lobbying industry since his release from prison, provided a very similar explanation: “[Lobbyists] probably put two and two together, and figured, ‘Well, why in the world should we register’? I think probably a lot of them figured, ‘Well, what do I need the headache for? I don’t need to be registered. The law doesn’t require me to register, so I’m not going to register.’ It basically makes it so that unless you want to register, you don’t have to register,” Abramoff told ProMarket.

What should constitute lobbying? How is lobbying today different from what has been traditionally considered lobbying? Who would one hire to advance their interests?

Potter shares from his personal experience: “I would probably hire a firm that has a public relations division as well as a lobbying division. When I was at Cigna, we worked with APCO Worldwide, which is a very large PR/lobbying firm in Washington. It has offices around the world now. It has grown to be a very substantial global operation.

“It started as an off-shoot of a law firm in Washington that did lobbying. It’s kind of a one-stop shop for lobbying and PR work. If you wanted to have a state grassroots or astroturfing group set up, that’s the kind of firm you would call that can do it soup to nuts.

“In fact, that’s exactly what they did during the health care reform debate in 2009 and the years leading up to that. As I mentioned in my book Deadly Spin, there was a fake grassroots organization that was funded by the pharmaceutical industry initially, and then by insurance companies, called Health Care America.

“It was purported to be a grassroots organization, but obviously, it was nothing of the kind. It was funded exclusively by industry and did not have a physical address. It existed only within the PR firm. That’s the kind of organization or the kind of firm that you would call, and they are all over the country. I think probably a decreasing amount is spent through traditional lobbying, because of other ways of influencing lawmakers and public policy.”

LaPira paints a similar picture: “The real underlying problem is that the kind of lobbying activities that happen today in the modern world—with advanced communications and the way white collar work operates—is that the way that lobbyists did their work 30 years ago is very different today.

“Lobbyists are engaged in all manner of activities, whether it’s PR, or social media campaigns, or what are so-called grassroots campaigns of getting voters and constituents to call their legislators about a specific issue. That too, I would consider lobby. If you’re relying on a traditional definition of a lobbyist meeting one on one with an officeholder to convince them or persuade them, that’s just not the way it works anymore.”

Hence, the 2007 amendment encouraged previously-registered lobbyists to stop registering. In other words, if the original 1995 act ended up providing less transparency, as LaPira and Thomas concluded, the 2007 amendment made lobbying less transparent still.

Abramoff agreed: “Virtually all consulting firms, strategic advisory firms, and PR firms are lobbyists. They’re doing their PR in Washington, DC. Washington, DC is not the PR capital of the world, it’s the government capital of the world.”

The two federal laws and the one in place in Chicago are strikingly different—the former, which does not include the 20 percent rule, being stronger and apparently more effective.

In a February 17, 2017 press release related to the Plouffe fine, U.S. Public Interest Research Group (PIRG) said that the Chicago definition is stronger than the federal law: “The fine, the largest ever imposed by the Chicago Board of Ethics, stands in stark contrast to federal lobbying disclosure laws that allow special interests to legally influence elected officials without reporting their work. Congress can follow the lead of this strong local example to pass ethics reforms that require transparency of all lobbying activity.” Therefore, adapting Chicago’s definition to the federal level would require more people active in lobbying in DC to register.

Did lawmakers include the 20 percent rule on purpose, in order to allow underground lobbying to prosper? “I don’t know because I wasn’t around when they did it. But let’s just say that if they were trying to do something on purpose, they couldn’t have figured something better than this,” says Abramoff.

Of course, lawmakers are well aware of the 20 percent loophole. Even Donald Trump, before he became president, addressed it. In an October 17, 2016 release he announced a “five-point plan for ethics reform,” immediately after first saying he wants to “drain the swamp” in DC.

His third point read: “I am going to expand the definition of lobbyist so we close all the loopholes that former government officials use by labeling themselves consultants and advisors when we all know they are lobbyists.” Trump did not elaborate which loopholes he was referring to, but it was broadly understood to mean the 20 percent loophole. So far, however, the administration has not addressed that issue.

“Mr. Trump claimed in his campaign rhetoric that he was going to attempt to close the ‘20 percent loophole.’ As far as I know, no member of the 115th Congress has yet to introduce a bill to change this. Frankly, shy of a major scandal, there’s very little incentive for a member of Congress to do this. I’m not holding my breath that anything major is going to change anytime soon,” says LaPira.

Maybe it is still there for a reason. In a January 30, 2017 analysis on Law360, a legal news service, Andrew Strickler wrote:

“The LDA definition has been the frequent target of critics who say it creates a loophole for former officials and politicians who jump to K Street,” K Street being a major DC street where many lobbying forms reside. In other words, at least some lawmakers prefer it that way because of the business opportunities it may present them.”

If indeed the law were to change, Abramoff would recommend that it be similar to the Foreign Agent Registration Act, which requires that agents representing the interests of foreign powers disclose their relationship with the foreign government. Such a law, Abramoff says, should include “the strategic advisors and the PR people–everybody who has anything to do with helping shape the lobbying efforts.”

LaPira recommends that lobbying reform should include three major components: “First, I think lobbying reform should focus on improving the quality of transparency. That has to be as broad as the actual, real-world activities that lobbies, public relations professionals, and media specialists are performing for the purpose of influencing policy outcomes.

“Second: the quality of the information that they are disclosing. There are a number of odd ways that lobbyists use to get away with technically reporting who their clients are, but those clients are often paper tigers and they’re hiding the underlying interests. There are often these issue-based coalitions that are really somewhere behind them, or corporate, or associations that aren’t actually being revealed.

“And finally, and this is frankly where I think I’m in the minority within many folks who look at this stuff, I think we need to get rid of the so-called cooling-off period. This period is precisely when actual or potential lobbyists that used to work in the government can do things underground. This is essentially when they learn how to be a shadow lobbyist, how to avoid being detected, and how to avoid triggering reporting requirements. I think if we got rid of those, but then required better transparency, I think that that would be a good solution.”

The role of money in politics and the influence of special interest groups on legislation, regulation, and policy in the U.S. has gained much attention in the last election cycle. It’s yet unclear if there is currently any real political will to address those issues, but one thing should be clear to people who want to “drain the swamp”: the size of the swamp is much bigger than the official numbers suggest. Therefore, the entrepreneurs and “plumbers” who will drain it are going to need much broader, deeper, and more aggressive measures and tools at their disposal.