A new Stigler Center working paper examines the political factors that shape competition in the wireless sector around the world and finds that pro-competition rules reduce prices, but do not hurt quality of service or investments.

During the summer of 2014, SoftBank-controlled Sprint abandoned its plans to merge with T-Mobile. The alleged reason was antitrust regulators who “would block a deal in an industry that is dominated by just a few large players.”

Following a meeting of SoftBank’s CEO Masayoshi Son with Donald Trump last December, both Sprint and T-Mobile signaled that the merger might still happen. Bloomberg wrote that “Son’s vow to invest in the U.S. and create jobs helped provide Trump with evidence he’s producing more work for Americans. It also scored points for Sprint, which was rebuffed by the Obama administration on a previous merger attempt.”

How would a T-Mobile-Sprint merger affect U.S. consumers? A new Stigler Center working paper, “Political Determinants of Competition in the Mobile Telecommunication Industry,” by Mara Faccio and Luigi Zingales may help to answer this question.

How the “rules of the game” affect the market

Economists tend to look at market concentration as the natural evolution of market forces. Yet, any industry, but in particular the mobile service industry, is deeply shaped by law and regulation. National governments have the power to shape the competitive landscape by defining property rights (number portability), allowing the use of the Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP, i.e., phone services over the internet), restricting foreign entry or ownership, choosing the rules of spectrum auctions, and choosing how antitrust laws are enforced.

By using the International Telecommunication Union’s Regulatory Tracker, Faccio and Zingales analyze how the rules of the game affect concentration, margins, and prices. They find that a government’s pro-competitive policy–from number portability to VoIP–has a significant effect in reducing concentration and prices. For example, on average, number portability reduces the market share of the two largest operators in a given country by 4 percentage points, reduces the price of a mobile-broadband internet plan with a 1GB volume of data by US$10 per month, and reduces the operators’ EBIDTA margin by 4 percentage points. Israel, whose regulation went from a pro-competitive (overall) regulatory score of 17.5 in 2010 to one of 52 in 2012, saw the average revenues per user (ARPU) drop by 33 percent and the local operators’ EBITDA margin drop by 10 percentage points.((The EBITDA margin and the ARPU are from GSMA Intelligence.))

Concentration does not have positive effects

Having established that the degree of regulation affects concentration, competition, prices, and margins, the authors tackle some of the claims made by the mobile industry.

One of these claims is that lower prices lead to lower quality and another is that lower prices also lead to lower profits, which leads to lower investments, which also hurt consumers. These claims do not dispute the notion that greater regulation leads to lower prices—but that the welfare consequences are negative.

Conceding that it is hard to test for welfare implications, Faccio and Zingales instead check how changes in concentration, competition, and prices induced by pro-competition rules affect quality of service and investments.

The authors employ a variety of quality measures: from the percentage of connections or coverage that are at least 3G or 4G to the speed of internet connections.

These tests provide no evidence that the industry’s claims are true. “We would not necessarily conclude that more competition leads to higher quality,” Faccio and Zingales write, “but we can certainly reject the opposite claim: that less competition leads to higher quality. In particular, there is no evidence suggesting that a government should tilt the rules in a non-competitive dimension to enhance the quality of service.”

Similarly, the authors do not find any positive effect of concentration on investments, employment, and wages.

Can regulatory choices that do not foster competition be justified?

If concentration-enhancing regulation does not have any positive effect on efficiency, why don’t all countries adopt pro-competition regulation?

One possibility is that governments favor concentration to raise revenues by taxing profits, either directly or through spectrum auctions. Faccio and Zingales find no evidence in support of this hypothesis.

An alternative hypothesis is that regulation is the outcome of the pressure of multiple constituencies (Peltzman, 1976). On the one hand, the operators want to restrict competition to make more profits. Operators may be able to capture the regulator to extract rents for themselves. According to this view, by restricting competition and increasing profits, regulations serve the interest of operators (Tullock, 1967; and Stigler, 1971). On the other hand, consumers want lower prices. Consistent with this hypothesis, Faccio and Zingales find that governments tend to favor competition more in more democratic countries, where citizens’ preferences are likely to carry more weight. By contrast, they find that rules appear to be tilted more in favor of producers when these producers are more politically connected. Thus, the overall conclusion, Faccio and Zingales write, is that the results are “broadly consistent with a view of regulation as a mechanism to create rents for the incumbents and, possibly, politicians” and therefore concentration cannot be expected to yield positive outcomes.

The effect of antitrust

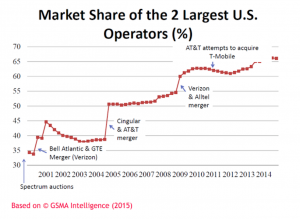

As the Sprint case shows, one important factor in shaping concentration is antitrust enforcement. Unfortunately, the degree of antitrust enforcement does not enter in the ITU regulatory tracker. For this reason, Faccio and Zingales resort to a “mini case study,” exploiting the difference in antitrust activism between the U.S. and the EU. Faccio and Zingales compare prices and quality between the U.S. and the two European countries whose level of regulation is closest to that of the U.S.—Germany and Denmark.

Comparing price levels, Faccio and Zingales note that the monthly revenue per unique subscriber in the U.S. is considerably higher than in Germany and Denmark: $67.6, $23.5, and $31.0, respectively.

The differences remain high even after taking into account that U.S. carriers subsidize phones and EU carriers do not: each year, U.S. mobile customers pay $280 more than German customers and $189 more than Danish customers. The national implications are huge: given the number of American mobile customers (233.2 million in 2015), this implies that U.S. operators enjoy a transfer of $65.2 billion relative to the German benchmark and $44.1 billion relative to the Danish benchmark. The authors note however that not all of this difference is a pure transfer, as the U.S. consumers have a better quality of service.

But they do estimate the level of abnormal profits of the four major U.S. carriers—Verizon, AT&T, T-Mobile, and Sprint—by building upon Lindenberg and Ross (1981), who link the difference between the market value and the book value of assets to the abnormal profits a firm can earn as a result of some stable market power position. Applying this method to Verizon, AT&T, T-Mobile, and Sprint, the capitalized value of abnormal profits in the U.S. mobile industry should be equal to $311 billion.

The takeaway

From protectionism to lax antitrust enforcement, President Trump is considering an array of new economic policies aimed at supporting businesses that “create jobs.” Faccio and Zingales’ findings highlight the potential hidden costs of these policies. A lax antitrust enforcement can cost American consumers billions of dollars every year.