Harvard Law School professor Einer Elhauge goes back to the days of Thurman Arnold, the head of the antitrust division in the FDR administration, and says the proliferation of horizontal shareholding creates a need for a reinvigorated and aggressive antitrust policy, of the kind that Arnold led in 1938-1945.

Corporate profits are at record highs, economic growth is low, formation of new companies has been low for years((J.D. Harrison, “The decline of American entrepreneurship — in five charts,” Washington Post, February 2015.)), and inequality is close to Gilded Age levels((Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, “Wealth Inequality in the United States since 1913: Evidence from Capitalized Income Tax Data,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 2016.)).

Professor Einer Elhauge from Harvard Law School believes that all these phenomena can at least partly be explained by a common problem. To prove his point he combines very recent empirical((José Azar, Martin C. Schmalz and Isabel Tecu, “Anti-Competitive Effects of Common Ownership,”(University of Michigan Ross School of Business, Working Paper No. 1235, 2015)) and theoretical((Daniel P. O’Brien & Steven C. Salop, Competitive Effects of Partial Ownership: Financial Interest and Corporate Control, 67 ANTITRUST L.J. 559 (2000).)) economics literature that has been gaining attention in the last few years with some insight into regulatory activities that go back more than 70 years.

Antitrust and the role that the extensive market power of corporations has on the economic activity has not been on top of the political, economic and academic agenda for many years. Elhauge, together with a group of law and economics professor, thinks that we should go back to the days when it was. In order to do that, we need to go back to the end of the 1930s—when president Roosevelt appointed a Yale law professor, Thurman Arnold, to head the government’s Antitrust division.

Arnold was appointed on March 1938 in the middle of the Great Depression, but according to Elhauge “he explicitly rejected the notion that antitrust enforcement should be relaxed during an economic downturn. He vastly increased antitrust enforcement, expanding the antitrust division to 583 lawyers by 1942”((Einer Elhauge, “Horizontal Shareholding”, 109 Harvard Law Review 1267 (2016).)).

This number deserves some elaboration; President Theodore Roosevelt is best known to students of history and antitrust as the Trust Busting president and indeed he made many political speeches about being a trustbuster. But he brought few antitrust cases. Indeed, his entire Antitrust Division only had five lawyers. By the time his distant cousin, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, took office in 1933, the Antitrust Division had expanded slowly to 15 lawyers, which is an amazingly small number for a nation of over 130 million people at that time.

In his five years in office, Arnold not only dramatically expanded the headcount in the division but also delivered output: he brought 44 percent of all the antitrust cases that were brought in the first 53 years of antitrust laws.

According to Elhauge “Arnold also made antitrust enforcement far more systematic and focused. Arnold deliberately used antitrust enforcement as a form of economic policy. He targeted industries that he thought were inefficient in a way that hampered economic growth. He also used multiple simultaneous lawsuits in each selected industry to thoroughly restore free competition at each stage of the industrial process. His strategy was ‘to hit hard, hit everyone and hit them all at once.’ He multiplied the effect of his expansion of prosecutorial resources by using prosecutions to obtain extensive consent decrees designed to go beyond the alleged antitrust violations to make markets as competitive as possible, as quickly as possible, in as many industries as possible.”

Elhauge adds: “Arnold further pursued an aggressive campaign to change the law on cartels, which resulted in the landmark May 1940 decision United States v. Socony-Vacuum Oil Co., argued before the Supreme Court by Thurman Arnold himself, which adopted a sweeping definition of pricefixing and made it per se illegal. Socony made antitrust compliance far less dependent on agency enforcement levels, both because the deterrent effect was so clear and because the change in antitrust law spawned a sharp rise in private antitrust litigation. Encouraged by this and other changes in antitrust law, the number of initiated private antitrust cases rose from 8 in 1937 to 110 and 111 in the fiscal years ending June 30, 1940, and 1941. Judgments for private anti- trust plaintiffs rose in 1947–1951 to an annual rate that was 16-fold the level in 1914–1940.”

In a recent paper, Elhauge states that “Arnold’s antitrust enforcement successfully lowered prices in the targeted industries” with his explicitly stated goal being “to have macroeconomic effects: lowering prices that were elevated by anticompetitive conduct so that consumers could buy more, which would cause firms to increase production and thus employment, which in turn would increase consumer purchasing power, further increasing production and employment.”(((Elhauge (2016)))

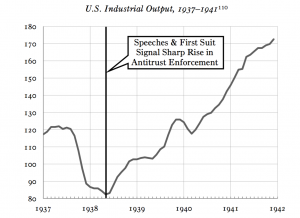

Elhauge notes that “Industrial output dropped 32 percent from July 1937 to May 1938, but after that began to rise by an average of 22 percent a year.” Elhauge thinks that the fierce antitrust enforcement had a lot to do with that.

Although “the production turnaround from the low point in May 1938 did start shortly after the April 14–16, 1938, announcements of increased federal spending and looser monetary policy”, Elhauge adds that “the production turnaround also followed shortly after Arnold and President Roosevelt gave speeches on April 28–29, 1938, that signaled a sharp coming increase in antitrust enforcement and that would predictably have started

to deter anticompetitive behavior. Arnold also met with leading industrialists in May 1938 to explain what the new antitrust enforcement regime would look like. These signals were quickly confirmed by action because Arnold initiated industrywide antitrust suits with remarkable speed. He was sworn in on March 21, 1938, and by May 18, 1938, Arnold had issued criminal indictments against 86 firms and individuals in the auto industry, prompting all but one of them to begin negotiating settlements within weeks.”

Elhauge adds: “other industrywide cases followed quickly, including July 1938 cases against the motion picture and dairy industries, an August 1938 case against the medical industry, and in the following months numerous other cases that over- hauled the housing, construction, tire, newsprint, steel, potash, sulphur, retail, fertilizer, tobacco, shoe, and various agricultural industries.”

By June 1939, he writes, “Arnold had ‘1375 complaints pending in 213 cases involving forty industries with 185 continuing investigations.’ Arnold’s cases produced quick results not only because he used massive criminal indictments to secure quick industrywide consent decrees, but also because merely launching an antitrust investigation sufficed to drop prices by 18–33 percent in various industries.”

Elhauge also writes that “what made the new antitrust policy unique was not only its timing, but also the extent to which it was an unexpected about-face. Roosevelt had pursued an anti-antitrust policy through the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) until the Supreme Court stopped him in 1935, and in the years thereafter he and his appointees remained, consistent with the policy views that prompted the NIRA, unenthusiastic about antitrust enforcement. The main objection raised during Thurman Arnold’s confirmation hearing was that his academic writings indicated he did not believe in antitrust enforcement. It was thus a true surprise, contrary to all market expectations, when Roosevelt and Arnold came out so strongly for vigorous antitrust enforcement at the end of April 1938.”

Elhauge, the Petrie Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, is not a historian but a law scholar who studies antitrust and occasionally serves as a consultant in antirust cases. He was chairman of the Antitrust Advisory Committee to Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign, and authored many articles and books on antitrust, contracts, corporations and health care law. His renewed interest in the law-professor-turned-monopoly-buster stems from his conviction that the United States economy is in desperate need of reinvigorated and aggressive antitrust enforcement.

When analyzing the state of industrial organization and competition in the U.S today, Elhauge is impressed and alarmed by the new literature that emerged in the last few years on horizontal shareholding. “Horizontal shareholdings”, he notes, “exist when a common set of investors own significant shares in corporations that are horizontal competitors in a product market.”

Recent papers [such as José Azar, Martin C. Schmalz & Isabel Tecu (2015); Azar, Raina & Schmalz (2016)] with economic models and empirical data show that “substantial horizontal shareholdings are likely to anti-competitively raise prices when the owned businesses compete in a concentrated market. Recent empirical work not only confirms this prediction, but also reveals that such horizontal shareholdings are omnipresent in our economy,” writes Elhauge.

Elhauge also argues that “such horizontal shareholdings can help explain fundamental economic puzzles, including why corporate executives are rewarded for industry performance rather than individual corporate performance alone, why corporations have not used recent high profits to expand output and employment,” and eventually he pushes this farther and claims that it also can explain “why economic inequality has risen in recent decades.” Elhauge thinks that stock acquisitions that create anticompetitive horizontal shareholdings are illegal under current antitrust law, and he recommends antitrust enforcement actions to undo them and their adverse economic effects.

He observes that a recent paper by José Azar, Martin C. Schmalz and Isabel Tecu((José Azar, Martin C. Schmalz & Isabel Tecu (2015) )) showed that “from 2013 to 2015, seven shareholders who controlled 60.0 percent of United Airlines also controlled large chunks of United’s major rivals, including 27.5 percent of Delta Airlines, 27.3 percent of JetBlue Airlines, and 23.3 percent of Southwest Airlines. More generally, institutional investors held 77.0 percent of the stock of all airlines operating in the average flight route from 2001 to 2013.” Their “econometric study shows that this sort of horizontal shareholding has made average airline ticket prices three to ten percent higher than they otherwise would have been.”

Guy Rolnik: Professor Elhauge – focusing on antitrust enforcement as the main culprit of many problems in the economy is not very common today.

Einer Elhauge: True, but that should change because antitrust could explain a few puzzles about what’s going on in the economy now. One puzzle is that we’re not growing very much, even though profits are huge. Normally, when you have huge profits, it invites entry and expansion, and then you get expansion of output and employment, which should drive unemployment lower and growth higher, but we were are not getting that effect. What we see instead is what you would predict if the causation were reversed, that is, if what was going on is that firms were restricting output and that was creating the higher profits; then you would expect to see low growth associated with high profits. I’m not the first one to suggest that market power might explain the combination of high profits and low growth, but I am raising the underlying question: what explains the higher market power? Why are we seeing more market power than before? One important contributor to that is this phenomenon of horizontal shareholding.

GR: Before we get into horizontal shareholding and its impact on market power and competition, let’s say we didn’t have the problem of the horizontal shareholding, would you still be as worried as you are about antitrust and its possible harm to the economy?

EE: Not as worried. I’d still have issues about antitrust that concern me. There have been empirical

studies showing that we’re allowing mergers that have raised prices at the margins, which would suggest that our merger enforcement policy is not quite aggressive enough. I also don’t think we’re doing enough about monopolization conduct. The agencies aren’t bringing monopolization cases to any serious extent.

Those issues would still concern me, but I do think, because we’re now doing nothing about the horizontal shareholding problem, it’s more likely to be a significant explanatory factor. At least with mergers and for monopolization, agencies are looking at mergers closely, and there is quite a bit of private enforcement against standard monopolization conduct.

We may be making mistakes on mergers and monopolization, but they’re more likely to be mistakes at the margins of under-enforcement, whereas with horizontal shareholding, the problem is we’re doing no enforcement at all, because nobody before has really recognized that horizontal shareholding creates market harms that justify antitrust enforcement.

GR: So, let’s focus on the horizontal shareholding. How big is the problem?

EE: Pretty big. The horizontal shareholding problem is this: Suppose you and I are competitors, but our shareholders are the same people. I don’t have much incentive anymore to take business away from you to make profits for me, because I’m just taking money out of one pocket of my shareholders to go into the other pocket of my shareholders. So competing would just harm our shareholders.

In the modern economy, in a lot of markets, it turns out that the leading shareholders are in fact the same set of institutional investors, because there’s a few institutional investors who have large stake holdings in almost every major corporation in America.

In those industries, it’s largely the same people. There is some evidence as well, that often there’s actual communication. The institutional investors have made a point of saying that they are “passive investors, not passive owners,” by which they mean they may be indexed (and thus not actively picking stocks), but once they own shares they try to influence management to act in ways that are beneficial to them.

Horizontal shareholding basically makes it more costly to gain business by cutting prices, because now, when you gain business, you are harming the shareholders who are your owners to some extent.

GR: How does the horizontal ownership translate into less competition? The relationship between asset management companies and the management of the public companies that they hold their shares is not direct?

EE: All relationships with shareholders are a little bit more distant in that sense, but these are the shareholders who are going to be voting on management compensation plans, for example. One of the points I make in the article is that the management compensation plans (that we see in most companies) make a lot of sense if the shareholders are people who are invested in rival companies and don’t want them to compete that much because our management compensation systems reward not just for individual corporate performance, but for overall market performance.

The fact that big institutional investors who are sophisticated are still not voting to change the management compensation systems suggest that they may have benefit from it in some way, and this theory explains why: For the institutional investors that owns stock in a set of firms, the less those firms compete with each other, the higher overall profits are. So the institutional investors don’t want to incentivize the managers of those firms to compete against each other. Doing so would be like, within one corporation, the board trying to encourage managers of various corporate divisions to compete with each other. Such competition among divisions owned by a common corporation does not help the corporation, and likewise competition among corporations owned by common shareholders does not help those shareholders.

GR: Do you have any evidence that management compensation is different in those public companies that share the same “Blackrocks”-asset management companies?

EE: Actually, just today a new empirical study came out((Miguel Anton, Florian Ederer, Mireia Gine and Martin C. Schmalz, “Common Ownership, Competition, and Top Management Incentives,” working paper (2016).)) with powerful proof that that is the case. This study also fits with prior empirical evidence that the more concentrated the market is, the less likely corporations are to pay based upon an individual corporate performance. The prior evidence also showed that the bigger institutional investor ownership has become as a share of stock ownership, the more we’re relying on methods of rewarding and punishing managers that depend upon market performance, and less just on individual corporate performance.

GR: It’s difficult to get attention to antitrust issues today in economics and policy. When we are looking at the 125 years of Antitrust, we are in a period of low activity and interest.

EE: For the first 48 years, from 1890 to 1938, antitrust was a huge political issue, and part of the reason why it was an important political issue was nobody really understood exactly what it meant. There was a certain incoherence about it. The consumers really had some uncomfortable feeling about bigness, but they couldn’t exactly tell when the bigness was bad, and when it wasn’t.

Antitrust enforcement tended to be a little mercurial and haphazard. Sometimes they’d sue you for being big, sometimes not, without a very well worked out theory about it, and not really that many cases. Teddy Roosevelt, even though he goes down in history as a trust buster, had only five lawyers in his antitrust division. It was very small potatoes really.

The big change happens in 1938 when Thurman Arnold is appointed the head of the antitrust division. He starts bringing tons of cases, and he starts bringing them based upon a very coherent theory that’s not about bigness. It’s just about efficiency. He doesn’t care if you’re big as long as you’re efficient, and lower prices. He doesn’t care about protecting the businesses either. It’s all just about increasing output.

He expressly links antitrust enforcement to macro-economic policy. His notion is if we can get the corporations to compete, lower prices will expand output, which will increase employment. With increased employment, people will b

uy more things, and business will expand more. It turned out to be remarkably successful. I think the evidence points pretty strongly to the conclusion that increased antitrust enforcement was a significant contributor to taking us out of the Great Depression.

At that point, antitrust was very successful, and very politically important. Thurman Arnold was a celebrity. He couldn’t be taken out of the job because he was too popular. But since then antitrust has in a sense become a victim of its own success. After Arnold, we had a general consensus that antitrust should be about efficiency and consumer welfare, with the result that antitrust went from being politically controversial to a technocratic subject that neither party talked much about. Antitrust enforcement just became accepted for both sides.

When I advised the Obama campaign in 2008, me and a committee of antitrust scholars, economists and lawyers came up with a bunch of long position papers. The only part that ended up seeing the light of day was just a two-page statement by candidate Obama. At the time, I was disappointed so little was said, but people told me afterwards that it was two pages more about antitrust than any other Presidential candidate had said between Ronald Reagan and Obama.

That suggested antitrust had become an issue with pretty low political salience. Now I think we’re in an interesting political moment where it does seem to me that might be a lot more interest in the antitrust policy as a political matter. We had candidate Hillary Clinton issue a very strong statement about it, and Elizabeth Warren just made a powerful speech in favor of antirust enforcement. Candidate Donald Trump also suggested some interest in competition enforcement.

More generally, there’s been a lot more policy concern recently about the impact of market power on wages and employment, and the fact that we have not had a very good economy for the working class for a couple of decades.

GR: Louis Brandeis, who had a lot of influence in this field 100 years ago, focused a lot on the political aspects of antitrust and bigness. Are his ideas relevant today?

EE: Some of it is quite relevant, and some of it is not. The part that I think is quite relevant was that he was concerned about the problem of interlocking companies and directorships. Back then, JP Morgan was sitting on the board of multiple corporations and inducing them all not to compete with each other. That problem is strongly echoed by the current issue of horizontal shareholding, which has a similar effect through common institutional investor ownership.

The other part of Brandeis’s argument was a concern about bigness for bigness’ sake. But I think that such a concern, if not linked to economic effects and economic efficiency just becomes ineffectual. Companies don’t know what to avoid because you can become big by serving customers and lowering prices and improving the economy. If you can get punished for that, that creates bad incentives. Perhaps recognizing the stamping out efficient bigness would be disastrous, enforcers only sometimes attacked big businesses, which made it very haphazard whether they would bring a case at all. It wasn’t an effective deterrence.

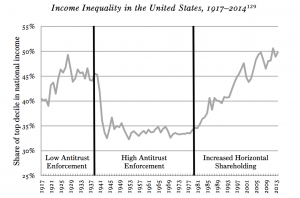

If you look at the data, economic inequality was very high during this Brandeisian period when antitrust enforcement was focused more on bigness than efficiency. Indeed, from 1890 until 1938, economic inequality was pretty high. It only really starts to drop in the period after 1938, which coincides with the period when we start to go active antitrust enforcement that would just focus on efficiency and consumer welfare.

GR: One could argue that the bigness that Brandeis feared can create an ecosystem that weakens incentives of regulators and experts to deal with non-competitive behaviors.

EE: That is a different problem, which is whether we will let the big corporations exert political influence. This may be a problem with Citizens United. Firms can further the public interest by being profit maximizers if there’s some external force channeling those incentives in a socially productive fashion. Being opposed to business bigness for its own sake is not the right policy. But allowing big corporations to influence politics is also a problem. It would be better to limit their political influence, but still allow business to get efficiently big, because that’s good for consumer welfare.

GR: The bigger the economic player – sometimes there are also more incentives for professionals, experts, for journalists to embrace its perspectives.

EE: Yeah, I think that’s really true. That’s where the jobs are. But that is true regardless of what your antitrust policy is. There’s always going to be more money in consulting for the big corporations, in part because they need advice not only during repeated litigation, but on a daily basis in order to figure out how to exploit their market power as much as possible, how they should price, and what they need to do to comply with laws.

So there’s always going to be a lot more people working for big corporations. But I don’t think the solution to that is to prohibit efficient bigness and hope that trickles down to less influence. That would lead to a much more inefficient economy, which would be bad for consumers and bad for employment.

The solution may be that the government has to lean against that influence by hiring its own people or subsidizing forces on the other side. In antitrust, we do have some features like that. We have treble damages, and we have private attorneys’ fees that the plaintiffs can get when they win a case. It may be that we need more efforts like that, but I don’t think that should alter the fundamental focus of antitrust law, which should be on consumer welfare.

GR: Would you say that most of the resources are in the hands of people who want to see less antitrust enforcement?

EE: Yes, I think that’s true today. We could use more balance in the funding. The government could play a role on that. The government should be the body that is representing consumer interests; they’re funded by taxpayers. It is true that in litigation the defendants have so much resources. Even the US government has a hard time matching the amount of resources that these corporate defendants ca

n throw at cases. In part, that is because antitrust has become much more technical and complicated. There’s lots of good reasons for that, but it’s probably fair to say that we have not sufficiently taken into account the under-deterrence problems created by the fact that it’s just so expensive now to bring any antitrust case, and all these technical issues create more doubt about winning them.

We used to have a lot more per se rules and strong presumptions, and there were valid economic critiques that they might be a bit over-inclusive, and that is a concern. But I think what we may be seeing is the cost of reducing that over-inclusion may be a lot more under-deterrence, because it just becomes so difficult to win any of those cases.

GR: In 1971, George Stigler wrote his seminal paper about the theory of economic regulation. How would he look at our antitrust enforcement today?

EE: Stigler was very much worried about regulatory capture. He was also quite skeptical about antitrust back in his day. On the other hand, I would say that the set of views such as the Chicago School of Antitrust had in 1981 would now be the left wing view in antitrust policy.

I was learning antitrust from Professor Areeda here [at Harvard] in the 1980s. His views used to be, I would say, the center-right view of antitrust, and those exact same positions are now the far left of antitrust, because antitrust has moved much more in a conservative direction since then.

GR: You think that even Stigler would be considered a leftist today, because antitrust policy has gone so dramatically to the right?

EE: Yes. For example, in the days when Chicago school people like Bill Baxter [head of the antitrust division of the Justice Department under Ronald Reagan] came into power, they were very strong on cartel enforcement. Now we have all these people who are undermining the ability to sue against cartels, raising theories that, “Oh, it’s impossible for the cartel to possibly affect prices,” even though you see the firms spending all this effort trying to do so. There seems to be this odd notion that people in cartels are wasting all their time trying to fix prices, when, in fact, they’re having no effect. So a lot of what is currently being pushed undermines as a result, the penalties or things like that for basic antitrust violations like cartels.

GR: You went further in your paper and claimed that there is correlation between the market power of firms in many industries and inequality.

EE: I think the level of antitrust enforcement could have a large effect on economic inequality and likely has a significant or noticeable effect on it, but not for sure.

What we know is economic inequality is very high during the period of low antitrust enforcement from 1890-1938. Economic inequality drops precipitously exactly when rigorous antitrust enforcement starts in 1938, then remains flat during a period of high antitrust enforcement from 1938 to 1980. Then economic inequality steadily increases back up from 1980 to now, a period during which we’ve had steadily declining antitrust enforcement, but also have had a steady increase in institutional and horizontal shareholding, something that we’ve never been really tackling.

Higher horizontal shareholder and lower antitrust enforcement could thus have significant effects. But there’s other stuff going on at the same time. It’s always hard to tease out multiple causation, but there’s a few intriguing pieces of evidence. One is that there’s some econometric work that responded to Piketty, who argued that capitalism itself inherently leads to economic inequality, by showing that actually it’s only when there’s market power that this happens. That work thus traces economic inequality to market power, rather than to capitalism itself. Likewise, the periods of higher economic inequality coincide with lower output growth, which is more consistent with lower competition than with a claim that economic inequality rises when firms or wealthy people become more productive.

GR: Your paper ends with the assertion that just by using current laws and the new data and models on the level of concentration after taking into consideration horizontal shareholding, we can take legal action in these industries.

EE: Yes, it is actually quite straightforward. Certainly for mergers — I mentioned that recent permitted mergers increased prices more than the agencies expected. I think part of the reason may be that, when the agencies analyzed the mergers, they never thought about the horizontal shareholding part of it. Even if all we change is how we analyze mergers, I think we’d approve fewer mergers if we considered the horizontal shareholding problem, and that might help with the problem that we have been allowing price-increasing mergers.

Also, when you look at our supposed merger statute, it’s not really a merger statute. The statute says any stock acquisition that may substantially lessen competition is illegal. All these institutional investors’ horizontal stockholdings were based upon acquiring stock. If you acquire stock, and this theory shows that lessens competition, then it’s illegal under the Clayton Act section seven, just on a straightforward reading. It really just requires recognizing the anticompetitive link between these stock acquisitions and what’s going on in the product markets.

GR: Do you think that the argument that the biggest asset management companies have been violating antitrust law for years has some merit?

EE: I think you have to go market by market, and figure out. It only matters in concentrated product markets, and you have to show that the horizontal shareholding levels rise to a level large enough, and there’s a technical way to measure it using something called modified HHIs [index of concentration that takes into consideration horizontal shareholding. G.R].

I would not say it’s a per se problem, but in a lot of markets, yes, I would say it is illegal. Now, it’s not a crime. It’s just something that is subject to civil enforcement and damages, but it’s something that I think they have to recognize they’ve got more liability exposure than they may have thought.

GR: If you were now picked up by the next president to be the head of the antitrust division in the DOJ, and when the next merger of insurance companies, or airlines would come to your desk, you would say, “no.” You would tell your people, “we’re looking at the modified HHIs now,” and not at the usual HHIs?

EE: First you look at the usual HHIs, but you also look at the modified HHIs. Really, the modified HHI is

just a further refinement. The HHIs really just crudely assume that there is no horizontal shareholding.

GR: So you would block a lot of mergers?

EE: Using this approach would definitely block more mergers than we’re blocking now. How many of them it would make a difference for, I don’t know. The modified HHIs do indicate that it would it make a difference for the airline mergers, and I think the data certainly shows that airline horizontal shareholding has increased prices given the market concentration those mergers allowed. Common experience suggests it too, because if you look around, it’s remarkable that with a huge collapse in oil prices, prices have not gone down, and every flight is totally packed that we’re on. There’s fewer options.

I think the agencies approve these mergers in good faith. I think they thought they wouldn’t be anti-competitive, but they didn’t think about the horizontal shareholding angle on it. At least, in the case of airline mergers, I think that would’ve made a difference, had they been thinking about it at the time.