Stephen Kohn, executive director of the National Whistleblower Center: “If your white-collar crime detection program is based on nice people having high moral values, corruption will flourish.”

Whistleblowers, studies show, play a crucial role in detecting fraud and corporate malfeasance. But while they serve an important role in uncovering wrongdoing, whistleblowers are exposed to enormous risks: A 2008 analysis by Alexander Dyck, Adair Morse, and Luigi Zingales found that whistleblowers often stand to lose much more than they gain by deciding to come forward. They are often fired or forced to quit under duress, shunned by friends and colleagues, and exposed to personal attacks that could harm their ability to find future employment.

As a way to incentivize whistleblowing following the 2008 financial crisis, the Dodd-Frank Act has equipped the SEC with new powers to protect and reward whistleblowers. The SEC’s Office of the Whistleblower, which was established in 2011 following Dodd-Frank, hands out financial rewards worth 10-30 percent of sanctions over $1 million to whistleblowers who come forward with original information that leads to a successful enforcement action—to date, it has awarded more than $111 million to 34 whistleblowers.

During a conference hosted by the University of Toronto’s Capital Markets Institute in January on the subject of whistleblowers, Andrew Call of Arizona State University said the SEC’s whistleblower program “changed the game, with respect to whistleblowing.”

Unlike the 1988 Insider Trading and Securities Fraud Enforcement Act—which offered rewards of up to 10 percent of penalties but had given rewards worth a total of $1.2 million to only six people—awards under Dodd-Frank have been more common than previous whistleblowing reward programs. Perhaps as a result, the program is considered a success by regulators: the program received 4,218 tips in the fiscal year 2016, its biggest year, compared with 3,923 in 2015 and 3,620 in 2014. It has received more than 14,000 tips so far. Former SEC chair Mary Jo White described it as “a tremendously effective force-multiplier…directing us to the heart of an alleged fraud.”

In early February, President Trump signed an executive order that sets the stage for a dramatic rollback of the Dodd-Frank Act. While Trump has since said he’ll “keep some” of Dodd-Frank even his planned “major elimination” of regulations, the president previously promised to dismantle President Obama’s overhaul of financial regulations, which he has repeatedly called a “disaster.” Since details about Trump’s planned financial reform are still scarce, it is unclear whether it will affect the SEC’s Office of the Whistleblower: some experts believe it won’t be affected, but there have been reports that House Republicans are targeting the whistleblower program as well.

Regardless of the fate of the SEC program, the participants of the Toronto conference all agreed that more protections and financial rewards are crucial to incentivize more whistleblowers. “For an employee to put their career on the line, it is unrealistic to think they’ll do it because they’re a nice person or they have high moral values,” said Stephen Kohn of the Washington DC law firm Kohn Kohn & Colapinto, who is also the executive director of the National Whistleblower Center.

Studies have previously shown that whistleblowers are motivated primarily by moral reasons. A 2013 study by Adam Waytz, James Dungan, and Liane Young found that fairness and justice are the primary drivers for blowing the whistle. Examining a survey of approximately 42,000 federal employees, they also found that when it comes to the decision to report wrongdoing, moral concerns are more significant than pragmatic considerations, such as personal benefits. In a piece published in ProMarket in August, Waytz argued that the current U.S. whistleblower program “prioritizes a relatively weak incentive—money—and rarely pays out” and that a more effective system would not do away with monetary rewards, but also recognize “the drive for justice motivating so many whistleblowing decisions” by, for instance, levying more meaningful fines against offenders.

Kohn, however, objected to the suggestion that a whistleblower program should be based on moral values. “If your white-collar crime detection program is based on nice people having high moral values, corruption will flourish. Why not just admit to it and make bribery and corruption legal? You’ll never catch it,” Kohn said.

The conference, which took place at the Rotman School of Management in Toronto, was moderated by Dyck and featured a panel discussion between Call, Kohn, Heidi Franken of the newly founded Office of the Whistleblower within the Ontario Securities Commission, and Peter Dent of Deloitte, who is the former chair and president of Transparency International Canada. The panelists discussed the enormous risks facing whistleblowers, particularly as new technologies increase the danger of their losing anonymity, and ways to provide whistleblowers with protections against retaliation.

Much of the debate, however, revolved around the issue of financial rewards for whistleblowers and their effects on whistleblowers, fraud detection, and markets. Despite the widespread media coverage that the financial rewards given by the SEC have received in recent years, the probability of receiving an award is still very low: only 0.2 percent of the tips given since Dodd-Frank went into effect have resulted in rewards, sa

id Call.

In his remarks, Kohn touted the success of the U.S. reward programs. “The essence of modern whistleblowing is to take the profit out of corruption,” he said. “We already know, through scientific studies, that the number one source of detection for white-collar criminal activity like securities fraud, foreign bribery, corruption in public procurement, are insiders: people who know what’s going on and can lead a regulator the right way.”

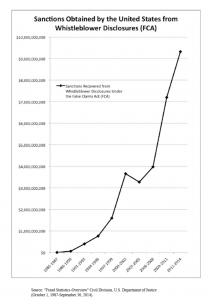

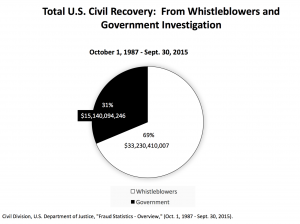

In countries where reward-based programs were instituted, like the U.S. and Canada, “the impact has been nothing short of profound,” said Kohn. “In 1985-1987, civil fraud collections were bringing in $50 million over a three-year period. Since being implemented, reward-based programs are bringing in $10 billion over a three-year period. Over a 30-year period, whistleblowers account for 69 percent of all fraud recoveries.”

The success of U.S.-based reward programs, he said, has had global implications. “Whistleblowers from around the world are coming to the U.S. because they lack protections in their own countries. They are turning over publicly traded companies that do business anywhere in the world. My new clients are from Russia, China, the Middle East, Brazil, Germany, because those countries lack any protection. The U.S. has already paid over $30 million to foreign nationals for reporting multinational companies, which is probably more money than whistleblowers have collected in any whistleblower program in the world, ever.”

Given the enormous risks involved, Kohn said, regimes that assume that whistleblowers are motivated by moral reasons, and therefore don’t require strong financial support, are destined to fail. “You need a realistic approach: no one in a position making hundreds of thousands of dollars who witnesses major corruption is going to turn it in if they’re going to go to the poorhouse and lose all their friends.”

Study: Firms seek to discourage whistleblowing with stock options

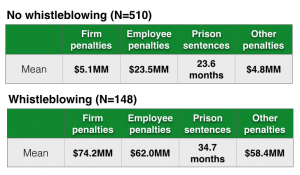

The rest of the event focused on the positive effects of whistleblowers on markets and their exposure to employer retaliation. Call, an associate professor at Arizona State’s W. P. Carey School of Business, shared insights from his recent search into regulatory regimes regarding whistleblowers in the U.S. Examining all SEC enforcement actions since the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, Call and co-authors found that whistleblower involvement is associated with larger penalties for firms and longer prison sentences for wrongdoers: firm penalties are 8.5 percent more likely when a whistleblower is involved than when not, and top executives are 6 percent more likely to face prison sentences when there’s a whistleblower.

“Time to discovery is shorter when whistleblowers are involved,” said Call. “Whistleblowers add value to regulators.”

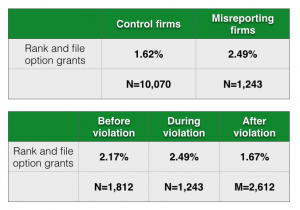

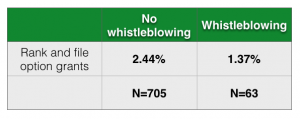

In a recently published study with Simi Kedia and Shivaram Rajgopal, Call and his co-authors tried to answer the following question: if regulators provide financial incentives to encourage whistleblowing, do firms provide financial incentives to discourage whistleblowing? In order to examine this, Call and his co-authors identified 663 firms that were accused of financial misreporting between 1996 and 2011 and then examined the number of stock options granted to rank-and-file employees during the period when the alleged misreporting took place.

What they found is that firms do indeed grant employees more stock options during periods of misreporting. While non-misreporting firms grant employees 1.62 percent of shares outstanding in the form of stock options, misreporting firms grant employees 2.49 percent. Misreporting firms, according to the study, grant 2.17 percent before misreporting, 2.49 percent during periods where they misreport, and 1.67 percent after violations cease.

This strategy, they found, is effective in discouraging whistleblowers: misreporting firms that avoided whistleblowing gave employees 2.44 percent of shares outstanding in stock options, while firms who were reported on by whistleblowers gave 1.37 percent. “If you don’t grant as much, the odds of whistleblowing allegations go up,” said Call.

Firms that don’t manage to dissuade employees from whistleblowing ca

n still retaliate against them. This is a real and ever-present danger, especially given that it’s increasingly difficult to conceal the identity of whistleblowers nowadays. “There are a lot of great ways to identify who a whistleblower is,” said Dent. “[As an employer], you have the content of what the whistleblower says, from the content of what they alleged, and you can narrow down who within the company would have access to that information.”

“If you have access to the actual complaint itself, which in most private companies you do,” Dent added, “there are great ways to identify whistleblowers. The way you use language, whether it’s in emails or on paper, is like a fingerprint. Today’s technology allows employers to download every email from workers. What you find with whistleblowers is that often they have made similar complaints about the issue to others within their organization. What you’re looking within that database for is the same spelling mistakes, same phraseology, same grammatical errors. Computers do it for you, and you can narrow down very quickly who is consistent, in terms of their use of language, as the whistleblower.”

Franken, the Manager of the OSC’s Office of the Whistleblower, concurred. “We tell whistleblowers: your identity may be revealed, not because of the OSC having to disclose it, but because through our investigation and our activities and our questioning, companies can put two and two together.”

What exacerbates the risk, participants said, is the poor legal protections available to whistleblowers. “Whistleblowers are not protected,” said Dent. “Our entire system of jurisprudence—In Canada and in the U.S.—is set up to protect the person that is being complained about by the whistleblowers. That is what our system of jurisprudence does: if you as a whistleblower come forward and complain about your boss, the system will kick in and the company may actually pay for the defense of the person you’re complaining about. If it goes into the criminal realm, there are all sorts of protections that automatically kick in for the individual that the allegations are made against. As a whistleblower, you’re already starting ‘behind the eight-ball,’ so to speak.”

This, said Dent, makes strong protections for whistleblowers crucial to regulatory regimes. The U.K. was brought up as a possible model. “Globally, the strongest protection for whistleblowers is in the U.K.,” said Dent. “What the U.K. has is a reverse onus on the burden of proof: once whistleblowers claim retaliation, their employers now have to prove that their actions were not retaliatory, instead of the whistleblower having to prove they were retaliated against. This changed the dynamic in the U.K., in terms of how many successful complaints there were about retaliation once they put that legislation into effect. That speaks to the need to protect whistleblowers and have an entire process in place that understands the motivations of management to discredit or downplay whistleblowers.”

In light of the risks facing whistleblowers, Kohn argued for strong financial support to whistleblowers. As an example of the possible benefits that financial incentives to whistleblowers might generate, he pointed to a former client of his: Bradley Birkenfeld, the former UBS employee who blew the whistle on the ways in which UBS and other Swiss banks helped American citizens evade their taxes. Birkenfeld, who served two-and-a-half years in prison for his role in the tax evasion scheme, received a $104 million award from the SEC in 2012, a decision that was controversial at the time.

“That made some heads turn, but it saved the IRS whistleblower program and it crushed Swiss banking, from a U.S. perspective. Fifty thousand Americans feared detection and voluntarily turned themselves in. You could never prosecute 50 thousand tax cheats in the U.S.; it would take years. Every Swiss bank closed all known U.S. accounts, and the U.S., as of the end of 2016, has collected $13.7 billion in sanctions from various banks and individuals. Many other whistleblowers stepped forward once they saw that it’s more profitable to turn in their U.S. clients than to serve them, that they could become rich doing the right thing.”

“People don’t like it when I say that, like whistleblowers are supposed to be martyrs or moral angels,” Kohn added. “Guess what? They almost all are. But don’t base your anti-fraud program on unrealistic assumptions of human nature. When they gave Bradley Birkenfeld that reward, the Swiss banks decided that they would exit illegal U.S. accounts. Swiss bankers didn’t become nice people; it was cost-benefit analysis. The risk of detection and enforcement and the price of getting caught were too high.”