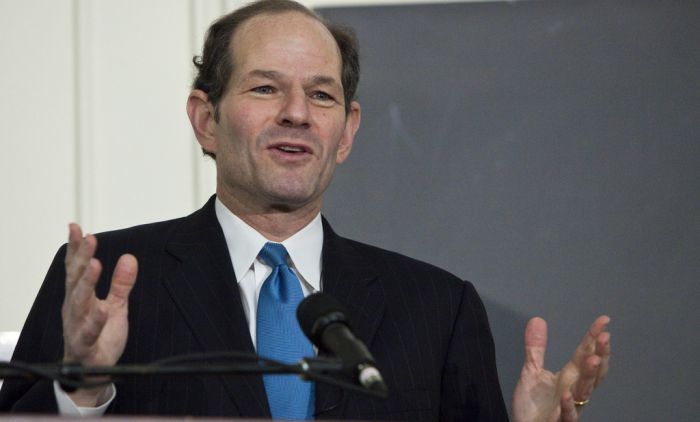

Former New York governor Eliot Spitzer talks about antitrust, digital platforms, economic concentration, and regulatory capture. Part 2 of 2.

In the first part of our interview with former New York Governor Eliot Spitzer, we talked about financial regulations and the impunity of corporate executives in the U.S. from criminal prosecutions.

Prior to becoming governor, Spitzer served for eight years as the New York Attorney General. His aggressiveness as attorney general, particularly his investigations into fraudulent practices in the financial services industry, earned him the nickname “The Sheriff Of Wall Street.” After being forced to resign as governor in 2008, Spitzer ran unsuccessfully for New York City Comptroller in 2013. He has since largely withdrawn from public life, focusing on running the real estate group he inherited from his father.

In the second part of our two-part interview with Spitzer, we talk about antitrust, digital platforms, and how economic concentration contributes to regulatory capture.

Guy Rolnik: You previously mentioned antitrust. Some fear that antitrust authorities are not responding well to the power of internet giants. Others argue that antitrust enforcement has gone down over the past 30 years regardless, for the same reasons that you mentioned: capture, revolving doors, etcetera.

Eliot Spitzer: Yes, it has. It has gone down, and that has led to an enormous concentration in many critical sectors.

The initial wave of rationalization for that was globalization. In other words, domestic antitrust enforcement was deemed to be, from a U.S. perspective, sort of anti-American because it meant bringing antitrust actions against U.S. companies when European companies were permitted to grow within the EU to the scale that they were—although EU antitrust enforcement these days is much more aggressive than it is in the U.S. The wave of internationalization was the cover story for the lack of antitrust enforcement.

GR: Not the reason, just the cover story?

ES: It was the cover, correct. And so, what we have now brought upon ourselves is this tremendous concentration and market power for a limited number of companies.

After ’08, there was some thought that things would change significantly. There was Occupy Wall Street, which I always said was emotionally satisfying, but was nothing more than a visceral scream of anger. There was no coherence behind it.

I don’t say that to be critical of the kids who protested. That is an important part of politics. But there was never any meaningful next step to explain or put in place a set of policies. And here we are, not many years later, and we have backed, in Washington, enforcement agencies affirmatively backing off from the limited steps forward.

The only reason that the consumer fraud protection agency is still pushing a fiduciary rule in any way, shape, or form, is because you have a holdover from the Obama administration, but they’re going to gut the fiduciary rule, unfortunately. They’re trying to eliminate that agency.

GR: Are there empirical data supporting the claims that it will spur growth? Do the people seeking to repeal these regulations believe that the U.S. is going to grow faster because they’re going to gut Dodd-Frank, or is it just pressure from the financial industry?

ES: There are people that do believe it. I’m a little hesitant here because I ask myself the same question, and I shake my head in amazement when I have conversations with people, and I say, “Name one loan that Dodd-Frank prevented you from making, or one bit of economic activity that would have occurred but for these rules you’re complaining about.” There’s so much capital sloshing around looking for places to invest. Nothing’s prohibiting that capital from going anywhere. We’re awash in capital.

There are different populations. There’s the angry voter who elected Donald Trump, who has internalized the political ethos that big government is strangling our economy. It’s false. It’s simply a false narrative, but there are people who believe it.

I’ll tell you a story that’s my canary in the coal mine: I’m building a big real estate project in Williamsburg, in Brooklyn. One of the contracts was [for] a curtain wall, the glass curtain wall for the building, which was a contract I gave to a manufacturer in Upstate New York, a rural part of the state. I went up there to visit the factory before I signed the contract. I met with the CEO, walked the floor and met with the workers. Every race and gender. This was in February 2016. Of the 200-300 people I spoke to—and this is New York State—not one was going to vote for Hillary Clinton. And when I asked why, they said, “Government’s killing the economy.”

These are workers on the floor of a factory who benefit from raising the minimum wage, from the healthcare laws that were passed, from environmental laws that keep their water clean in an area that had some pollution problems, and yet the emotional argument that has been made by Fox News and Trump registered with them in a way that defies logic and reason.

It’s a long answer to your question. Do some people believe it? They do. There are bankers—rational people, decent people with whom I have a drink or have dinner, people with whom I do business—who say, “We’ve got to get rid of Dodd-Frank, because it’s keeping us from making loans,” and I say, “Name one.” Are they wrong? Yes. Do they believe it? They actually do, yes.

GR: When we look at corruption and regulatory capture, where would you put the focus today?

ES: Challenging the status quo is a very hard thing to do. Standing up to existing power structures is enormously difficult, and most people in government just don’t want to do it. The status quo moves forward and survives sequential shocks, even those as fundamental as the crisis of 2008.

Very few elected officials, or regulators, or regulatory agencies, have the fortitude to say “We have to do something fundamentally different.” They just don’t have the capacity to say it.

GR: So who is going to challenge this status quo?

ES: On the one hand, I’d like to be an optimist and not a pessimist. And so, on the one hand, the U.S. economy and the global economy are in acceptable shape, unemployment is down, GDP is growing a little bit more rapidly, and the financial sector is slightly more stable than it was over 10 years ago. But the trend line in wage growth is still horrific.

The Donald Trump presidency will accelerate the rise of China by about 50 years. By that, what I mean is that if China’s advantage was beginning to change the balance of power almost as a law of physics, what the U.S. had as the world leader derived from a moral authority that was based upon our beliefs in freedom, the morality of our leadership, having stood for certain fundamental principles over the last 50-80 years, since the ascension of the U.S. as the global leader. That has now been thrown away.

Trump has destroyed the leadership role of the U.S. in the global context, and left a void that is being filled by China. Putin is, I think, a short-term historical player. He’s a petty thug whose nation can’t economically support his agenda. China can. I think that Trump’s presidency will be viewed, unfortunately, as a pivot point in that dynamic.

I’ll show you one little chart, which I think explains the politics of the moment. It’s a very simple chart. Everybody learns it in Econ 101.

Wages and productivity aren’t in a line. They’re collinear. In the U.S., that was the case until 1973 or 1974, then wages flatlined. The area under this triangle, which should have gone to labor through wages, ended up going to capital. This is the redistribution of wealth that has led to the anger in the American public. That redistribution of wealth is a combination of technology, concentration of power, globalization, all the issues we’ve been talking about. But it’s that redistribution and frustration that has led to the rise of either the populism of the left or the anger of the right.

GR: I understand this, but the people that were actually making the decisions are informed people, and some of them are backed by smart people in industry and academia.

ES: Here’s the beautiful thing about the human mind: We persuade ourselves to believe what we want to believe. It makes life livable. That’s the best answer I’ve come up with, because I have the same problem you do, which is I look at these folks, and I say, “Do you really believe that?” These are smart people, and they’re saying things that I think are palpably false. I look at them in amazement, and I say, “You can’t possibly believe that,” but they do.

GR: Could they be right? Could you be missing something?

ES: I hope not, but in a way, I’m tempted to say I hope so, maybe. Nothing’s working terribly well right now, but I don’t know. I don’t think we’re missing anything. I view the healthcare debate in the U.S. as a paradigm for what you’re talking about: for seven years, screaming, shouting “repeal, repeal, repeal,” without giving any thought to what they’re going to do as the alternative. Then, when the moment of truth comes, suddenly a few Republican senators wake up and say, “Wait, you can’t do that.” The other 49 were happy to go forward with an idiotic plan. It took one or two who were pressured by the reality of taking healthcare away from 20 million people to put a halt to their game. Think how much venom, anger, screaming, and shouting just on that one issue.

GR: You could say that the Trump presidency is the left’s punishment for being pro-business, pro-Wall Street, pro-concentration and pro-big money for 30 years, instead of being pro-market?

ES: The Trump presidency has been many things, but certainly, one causative factor is that the Democratic Party failed to confront the structural issues over the last 15 years. We became the party of the status quo.

Not to be self-referential, but I will tell you, when I was Attorney General and we were doing what I call our “Wall Street cases,” there were precious few voices in the Democratic leadership that wanted anything to do with it.

GR: Maybe the differences between the left and the right are not as big as they were 40 years ago, when it comes to special interests and big money?

ES: That’s true. That’s absolutely the case.

GR: Were both conquered by money?

ES: Let me state it in a less purely cynical way—it’s not that I’m not cynical, trust me. The status quo is enormously powerful. Very few people really want to look at it and say, “The system’s not working. We’ve got to do something different.”

If you’re an elected official, what brought you to the dance is what you want to keep doing. By definition, you’re there as a consequence of the current system, so how bad can it really be?

GR: Do you think that courts have played an important role in producing a countervailing force to captured politicians and regulators?

ES: The courts have done better than legislative bodies.

GR: And regulatory bodies?

ES: Oh, yes. I think the courts have at least pushed forward in the domain of civil rights and environmental enforcement and confronted issues before legislators.

GR: And when it comes to the power of corporate America, are courts more independent or immune to the pressure of money?

ES: The courts have been not so great in that domain, with the exception of Judge Jed Rakoff and Judge Richard Posner, of all people, whose cycle through free market mania back to cynicism about corporate governance has been a remarkable thing to watch. I don’t read his things anymore, but back when I was actually a lawyer, we used to fume at some of his free market pseudo-logic. He at least had the intellectual integrity a few years later, after the crisis, to say “Hey, guys, you know what? We got it wrong. That didn’t work out so well.”

GR: In an interview with Professor Luigi Zingales during our conference on concentration, Judge Posner said that Congress is owned by the rich, but when it comes to his views on antitrust, those have not changed much in the last few decades.

ES: He hasn’t come back on that. He has [changed his opinion] on some issues related to corporate shareholder power etc., but at least, some of his opinions were extreme.

GR: How important was Citizens United to the development of the dynamics we are talking about?

ES: I think more fundamental is what you said earlier, which is that the Democratic Party didn’t really stand up. In terms of money, Hillary spent more than Donald Trump by a ratio of two-to-one. You can’t blame that election loss on money. It was [the] message. The right message, obviously, would have beaten Donald Trump. The wrong message didn’t beat him. I think we take the easy way out when we blame the money that was let loose by Citizens United as being the sole causative factor.

GR: If Hillary Clinton wasn’t perceived [to be], or in fact was, captured by big money, might she have won?

ES: One small example—perhaps not so small—was the Goldman Sachs speeches, which I think were symptomatic of a larger skepticism that the public had about her loyalty to some of the core beliefs that she claimed to hold.

It wasn’t just, “OK, a politician gave a speech and got paid for it.” It was the secrecy of those speeches that became metaphorical for the public’s view, or enough of the public’s belief, that there was a lack of consistency between her articulated views and how she would govern.

GR: And now we see that Obama is also starting to give speeches to business groups.

ES: I’ll tell you what: I wish that the president of the U.S., once leaving office, were given a salary – let’s say $5 million a year, tax free, in perpetuity—and precluded from getting paid for anything else.

It is still a unique position in the world. I would like to see the people who have held that position keep themselves separate from the temptation to either earn money, or the public’s view that they’re doing something to earn money.

GR: When we look at the world out there, we see that there are very few Paul Volckers or Eliot Spitzers who, after leaving office, don’t go to work for the largest regulated firms.

ES: Paul Volcker, I’ll agree with you.

GR: People would push back on my question and say, “Paul Volcker is a good example, but Eliot Spitzer comes from a wealthy family, so he can afford this career path.”

ES: Precisely. Take me out of the equation. It may not be a coincidence, having said that, that some of the leading voices that did push back against the establishment—take Teddy Roosevelt or Franklin Roosevelt—had the financial wherewithal not to care.

It’s a very 18th century British perspective. It almost speaks to having a House of Lords. “Oh, we need a House of Lords, because they’re above the fray of politics.” There’s something that we feel uncomfortable in articulating it that way. Who knows? There it is.

Disclaimer: The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.