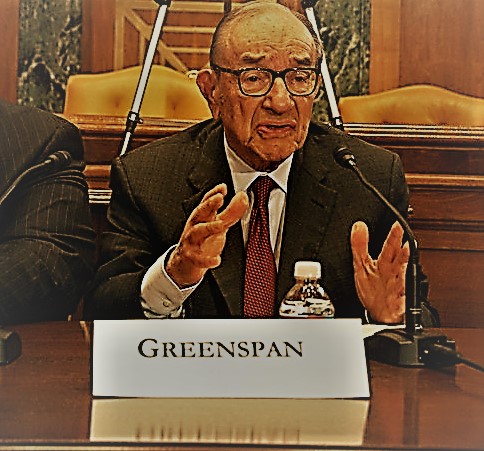

“I am in a state of shocked disbelief,” former Federal Reserve chair Alan Greenspan said during the 2008 crisis, before confessing: “I found a flaw in the model that I perceived is the critical functioning structure that defines how the world works.” Today in Chile, the same business coalitions that have always demonized state intervention are asking for help: Will they admit their approach was as flawed as Greenspan’s?

“We are going to require government support,” LATAM Airlines CEO Roberto Alvo said this week, as the Chilean airline’s stock plummeted by as much as 80 percent due to the coronavirus pandemic.

The leaders of the wider business community agreed. “There are companies of public utility such as airlines that are going to require aid,” the president of the Confederation of Production and Commerce (CPC), a group representing Chilean businesses, said. “This is an industry that is being supported by developed countries, and I do not see why it should be any different in Chile,” the leader of the Federation of Chilean Industry (Sofofa) added.

Those are extraordinary statements, coming from pressure groups that for decades demonized state intervention in the economy.

It is true that airline bailout is a worldwide issue: According to the World Travel and Tourism Council, airlines are negotiating with 75 governments. Norway, Finland, India, and Australia have already offered hundreds of millions in aid packages for their airlines. Germany announced plans to buy shares in large companies like Lufthansa, and Italy announced the nationalization of Alitalia.

Although in Chile this sounds like heresy, dozens of other countries have state airlines, including the two best companies in the world according to the Skytrax ranking: Qatar Airways (through which that emirate owns 10 percent of Chile’s LATAM), and Singapore Airlines.

Yes, the celebrated airline of Singapore, the country that leads the rankings of economic freedom in the world, is a state airline. The Singapore treasury is also the owner of telephone companies, internet providers, banks, and technology companies. And 88 percent of Singapore’s inhabitants live in state housing. Why? In the words of its prime minister, Lee Hsien Loong, for reasons of “pragmatism: we are willing to do everything that works.”

And when these giant companies remain private? In 1953, former General Motors CEO Charlie Wilson was appointed the US Secretary of Defense, proclaiming, “What is good for GM is good for the United States, and vice versa.” These giants are “too big to fall”: As their bankruptcy would generate an economic and social catastrophe, governments are forced to rescue them.

The question is rather how to do it, to ensure that tax money does not end up in the pockets of owners or executives. Last week, the conservative French finance minister said that France will prevent the bankruptcy of large companies, “even nationalizing [them] if necessary.” The same plan was advanced by his counterpart, also a conservative, from Germany.

In Chile, the Chicago Boys’ vaunted ideology of non-intervention by the state went to waste in the crisis of 1982. All Chileans, through the treasury, became guarantors of the private external debt of the large economic groups.

We, the citizens of Chile, financed a “preferential dollar” for them, with a loss for the treasury of about a third of GDP. It was, in the words of former finance minister Nicolás Eyzaguirre, “an embarrassing case of socializing private losses[….] Although the owners of the banks lost their capital, the owners of the companies—which in many cases were the same people and used the banks as their treasury—were clearly rescued with public money.”

Following the crisis, banks have successfully lobbied to relax regulations, and today they are among the most profitable businesses in the country. A similar thing is happening with the agricultural lobby, which cries out for state intervention every time the dollar falls. And when the dollar is through the roof, like today? Let the dirty state take its hands off the market!

During the subprime crisis of 2008, GM was rescued by the US government. The same happened with banks and industries. The former all-powerful Chairman of Federal Reserve Alan Greenspan had to appear before Congress to defend his deregulation policies that had triggered the crisis.

“[Everyone has] an ideology…a conceptual framework with the way people deal with reality,” Greenspan said at the time. He also confessed: “Those of us who have looked to the self-interest of lending institutions to protect shareholders equity, myself especially, are in a state of shocked disbelief… I found a flaw in the model that I perceived is the critical functioning structure that defines how the world works.”

If governments in Europe or Asia can quickly come to the rescue of, or buy, large companies that are in trouble, it is because for decades those governments have been owners or partners in those companies, whose fate they understand to be closely linked to that of their country.

If the crisis deepens, perhaps Chile will have no choice but to rescue LATAM and other large companies. But in order to have this debate, Greenspan’s Chilean followers should start by recognizing that their ideology has a flaw.

Either that, or admit that this ideology is a convenient veneer disguising the usual interests: privatize profits and socialize losses. And for that, nothing is more convenient than being a neoliberal when the cows are fat, and socialists when the skinny cows arrive.

Daniel Matamala is a Chilean journalist. He works for CNN Chile, where he hosts 360 and CNN Prime. He also has a career as an investigative journalist and is the author of six nonfiction books. In 2018, he participated in the Stigler Center’s Journalists in Residence Program. A previous version of this article was published in La Tercera, one of the most important newspapers in Chile.

Pro Market is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.