“Blockchain technology is threatening to remake the financial system from the top down in a way that threatens the existence of all the banks, stock changes, and all of the legacy financial institutions. I expect that within the next 10 years, probably half of the banks will be gone.”

Blockchain, the technology that underlies cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, has become all the rage in the financial world in the past two years. Since 2014, banks like Citi and Goldman Sachs, stock exchanges like the New York Stock Exchange and NASDAQ, and other financial services firms have each poured millions of dollars into the technology. Initially skeptical about digital currencies, the industry was quick to jump on the bandwagon.

Earlier this year, four of the world’s largest banks—UBS, Deutsche Bank, Santander, and BNY Mellon—announced the development of a new form of digital cash, meant to allow financial institutions to clear and settle financial transactions over a blockchain. The banks are aiming to launch it by early 2018, and hope to make it the industry standard.

“The gold rush has begun,” said New York University professor David Yermack last week, during a visit to the Stigler Center. Yermack, who has researched blockchain technology extensively, is not impressed with the banking industry’s latest attempts to co-opt the blockchain technology, which is currently threatening to do to banking what Napster and other peer-to-peer file sharing services did to the music business two decades ago.

“Blockchain technology is threatening to remake the financial system from the top down in a way that threatens the existence of all the banks, stock exchanges, and all of the legacy financial institutions,” he said. “I expect that within the next 10 years, probably half of the banks will be gone. They will probably merge with each other in a series of defensive mergers. Many of them are actively using current regulations to try to co-opt this technology into their business models, at least in a limited way, to forestall what looks like a serious day of reckoning that may not be too far in the future.”

Stock exchanges, too, are threatened by the new technology. “I am not sure that stock exchanges, or things like the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, will continue to exist. If they do, they would probably be greatly reduced in size and streamlined, and ultimately become more beneficial to the customer.”

A telling sign of the future, he said, was the growth of money transferring services like PayPal and M-Pesa. M-Pesa is a mobile phone-based money transfer and microfinancing service operating in Kenya and several other countries, which is partly owned by Vodafone. “Vodafone found itself registering for a banking license—it didn’t realize it was in the banking business until this thing succeeded wildly. I asked people in Kenya: ‘doesn’t this make Vodafone your central bank?’ And they said: ‘We trust Vodafone more than we trust the central bank.’”

Ultimately, however, services like PayPal and M-Pesa are still dependent on existing structures, said Yermack. Paypal depends on Visa and MasterCard. M-Pesa depends on Vodafone. “Blockchains don’t use intermediaries. Bitcoin is completely different, because there is no third-party central authority. The removal of the third party is really what the innovation here is. To quote The Economist, it’s a trust machine.”

Blockchain technology is poised to remake and disrupt the financial industry from the top down, said Yermack. “This calls into question why we really need to have banks at all,” he said. “We’ve had banks for thousands of years, banks are some of the oldest institutions in society, but we seem to have come up with a way that questions whether there is any value to them. Do they perform a service we couldn’t just perform collectively by ourselves?”

As banks are rushing to invest in the new technology, he added, they are also doing something else: “searching for how they can use this technology to create barriers to entry that will allow them to prolong their franchises, maybe for another five to ten years.”

In the long run, he said, “it’s a losing proposition. The models the banks are using are really quite restrictive, not taking full advantage of the technology. They will probably lose out in the marketplace, as the younger generation is much more comfortable with hand-held commerce and peer to peer transactions, and this will cause the banks to wither away.”

Could the blockchain really alter the balance of power within the financial industry? In a series of recent papers, Yermack argued that blockchains could potentially upend corporate governance, central banking, and the entire financial system.

In order to better understand the blockchain’s potential effect on concentration and competition within the financial system, we recently interviewed Yermack, the Albert Fingerhut Professor of Finance and Business Transformation at New York University Stern School of Business, for ProMarket. Below is a full transcript of the interview:

Q: In your paper “Corporate Governance and Blockchains,” you write that the blockchain could “lead to far-reaching changes in corporate governance.” What are those changes?

There’s really a wide range of things, but much of finance is conducted through middlemen. The simplest example would be that when you borrow money, you use a bank to bring savers and investors together. But what blockchains do is open up the possibility of peer-to-peer markets, so that a firm could issue equity directly to investors without the investment bank building the book and recruiting the owners and so forth.

Removing the powerful intermediaries could change quite a few things: the way that creditors monitor and decide to invest, the way shareholders monitor and vote. Without the involvement of intermediaries, which are not only imposing their own advice but charging a fee every step of the way, there’s a chance to reduce the cost of capital and also have much closer relations between investors and the managers of a firm.

Q: What are the implications of removing these intermediaries?

I think a lot of managers are able to rely on intermediaries as an extra line of defense in areas that range from shareholder activism to things like bankruptcy negotiations. The whole way that firms finance themselves and deal with their investors may be much more direct—and much more confused as well—but I think it won’t be the same, in the sense that you can’t turn back the clock and go back to the old system once people start to use this on a widespread basis.

One interesting thing is the transparency that you get, because when people trade on a blockchain you have what is called a shared ledger—essentially, everybody can see everybody’s trades and investments and so forth. For managers, all of their insider trading, whether legal or illegal, would be very visible to people.

When shareholder activists invest, other shareholders would see them investing. Currently they can hide behind disclosure rules that don’t force them to declare themselves until they own 5 percent. If somebody sells a share people would see the sale immediately, rather than waiting for the filing that may take place a couple of days later. It has the potential to provide much more accurate information to everybody in a more timely way. It can also make it easier to monitor managers and has the potential to lower the cost of capital if people don’t charge the same kind of risk premiums or worry about the same problems they worry about in the current system.

Q: So the blockchain could, potentially, reduce the risk of wrongdoing?

Yes. Fraud becomes much, much harder in a system like this. It’s a much more transparent system where not only you can see people’s transactions in real time, but also to go back and doctor entries in the ledger is all but impossible.

If you think about what fraud means in a company today, it often means just going back to the ledger and adding an extra zero, or erasing a transaction, pretending it never happened or dating it to an earlier date so it falls into a quarter when it really didn’t occur. On a blockchain you can’t do any of those things. The data is written in a way that it’s indelible.

Q: There are economists and analysts that point to blockchain technology as a potential answer to the financial system’s security problems. Others, however, suggest that Bitcoin, for instance, is vulnerable to issues of its own.

Not security issues. What’s happened in Bitcoin and received a lot of publicly is that people steal Bitcoins from digital wallets and from custodians who basically do a bad job of protecting passwords. But the Bitcoin network has been extremely resilient to any kind of fraud or hacking. It’s really surprising how stable it’s been—it’s been operating pretty much continuously without any sort of technical disruptions for eight years.

It does have issues about capacity. The main problem with Bitcoin is that it’s grown so fast that you need to widen the highway if you want to accommodate more traffic. But in terms of technology, the great promise [of the blockchain] is that a lot of the risks that you have in the current financial system seem to be overcome by this. In the retail banking system there are all kinds of hacks and frauds, with credit cards companies as well. In consumer finance and credit markets, there’s huge potential for banks to be able to deal with each other on a more secure basis, or for clients to bypass their banks altogether.

One of the interesting things about this technology is that it puts a lot of responsibility on the end user. You don’t necessarily have the government deposit insurance that you have under the current system. There will be people who are uncomfortable with this: the data shows a really heavy skew toward younger users and people who are better educated.

Probably for a generation or two, legacy banks will have a pretty reliable clientele of people who aren’t comfortable with computers and feel they don’t want to take on the task of protecting their own credentials and passwords. But if you realize that you’re paying the credit companies 3 percent of every swipe, that’s sort of what’s at stake here. You could be giving yourself a 3 percent raise if you agree to do it yourself without relying on MasterCard and Visa to do it.

Q: In “Digital Currencies, Decentralized Ledgers, and the Future of Central Banking” (written with Max Raskin), you posit that digital currencies could be seen as competing with central bank fiat money, and suggest that in the future central banks may use the blockchain themselves. Right now, the most prominent application of blockchain technology is Bitcoin, which isn’t very reliable as currency.

Bitcoin has a lot of weaknesses as a type of money. One idea that is actively being looked at by many governments is using central banks to start issuing sovereign currency on blockchains. That would really be a game changer, because you wouldn’t need the fractional reserve banking system any longer—you could just have everybody with a digital wallet account at the central bank. This ironically revives an idea that came out of the University of Chicago in the 1930s, called at the time the “narrowing” of the banking system.

I’ve lost track at this point, but there are probably 20 to 30 central banks around the world that have actively opened up a program looking at taking the banknotes and coins that you now have out of circulation and putting the national currency onto a blockchain. That would give central

banks much more precise control over monetary policy and the ability to do things like charging negative interest rates which are rather difficult in today’s world.

There are already two African countries who have done this in the last month, and it wouldn’t be surprising if you saw a major economy like Sweden or Singapore do this within the next year or two. This is moving much faster than you might have expected.

Q: How would future applications overcome Bitcoin’s obstacles?

You’re also seeing uses of blockchain right now in supply chain management, in companies like BHP Billiton. In the port of Rotterdam, it is used for the tracking of cargo. Any application where you have a database that needs to be constantly updated to document the interactions between people is a candidate for this. There are some very interesting uses of this in the electrical power industry, where there are neighborhoods that have solar panels that have hooked themselves together in a single blockchain to essentially share power from one house to another as it is generated. If you scale this up, you don’t really need the electric company any more, which is a middleman in the same way that a bank is. A lot of this is still in the R&D stage, but some of these applications are live.

The governance of these things is an interesting problem: they really didn’t think this through with Bitcoin itself. One of the reasons for the volatility and the limits on the growth of Bitcoin is it was designed from the start to be small. It has a limit on the block size and a cycle time of 10 minutes per block. These were constraints put in place 8 years ago when Bitcoin was like a hobby or a demonstration vehicle. Now that it’s shown its resilience, it needs to be scaled up, but there’s an entrenched group, the miners, who run this thing on a day to day basis. They like the system the way it is now because they are profiting from it. If they were to support scaling it up, it would undercut a lot of the investment they made in computers.

Future applications are going to need to be much more flexible to take account of that. If you want something to be a currency on a large scale, you have to accommodate much more volume than Bitcoin itself can. Ultimately Bitcoin itself can only handle about 7 transactions per second—as long as that is the limit, it can’t be taken seriously as a type of money

Q: So in order for blockchain technology to have wider applications, we need to leave Bitcoin behind?

That is my view. There are people who really think that the Bitcoin blockchain will end up being the one big blockchain for the world and that some type of solution will be found to scale it up. I don’t see it happening anytime soon. Another reason is that Bitcoin uses so much energy in the validation process and the mining—there’s not enough electrical power in the world to support all the mining that might take place.

I think that Bitcoin has some design issues that could not have been understood 8-9 years ago but have become really apparent over time. It’s easier to design a new system from scratch than trying to put band-aids on this one and get people to agree to changes.

Q: Digital currencies like Bitcoin are currently unregulated, and that has made them behave more like speculative investments than currency. How can governments regulate the blockchain and peer-to-peer finance?

This is the huge challenge, because these things don’t really exist physically in any location. If you wanted to issue equity or raise debt on a blockchain, it’s not clear what regulator—if any— would have the authority to make the rules and how they could ever enforce them.

There’s a school of thought that says people should be working hand in hand with the regulators we have today. A good example of this would be in Australia, where the ASX stock exchange is retrofitting themselves on a blockchain platform, but they’re doing it hand in glove with the national regulator. A lot education of the regulators has to take place, but ultimately the belief is that it’ll attract a lot more business if it has this stamp of approval [from the regulator].

That remains to be seen, I think a lot of the clientele for Bitcoin really comes from people who dislike regulation. There’s a huge libertarian community for whom the inability of any regulator to meddle in the thing is really a selling point.

There’s probably enough room in the market for both approaches: I think you’re going to see some wildcat blockchain people, but also people working very closely with the regulators.

Governments around the world are going to have to develop a capability to deal with this technology on its own terms. I think writing the rules for this and figuring out what you need and don’t need to regulate anymore, and what are the new problems that you need to regulate for the first time, is going to involve a lot of trial and error and people feeling their way along. But it’s encouraging that you are seeing a lot of countries putting out white papers or starting intergovernmental agency groups to study this. Most of the U.S. regulators have been holding conferences and calling in experts for seminars and so forth. There’s a real effort to get up to speed which is much further along than it was a year ago.

Q: Assuming those technical and regulatory problems can be overcome, how would widespread use of blockchain technology affect the power balance within the financial system?

The blockchain gives you lower cost, faster execution, much more transparency. I think for outside investors, the speed and accuracy of the information that you get is going to enable you to drive a much harder bargain. Whether you’re trying to borrow money or whether you’re thinking of investing in a company, I think it’s very much to the advantage of investors that this technology will reduce transaction costs and make the entire round-trip experience much cheaper and less risky than it’s been on the past. It’s a real improvement in the technology of capital raising and ultimately should really benefit everybody if it’s handled the right way.

Q: Big banks, investments banks, the intermediaries you mentioned earlier might be cut out, how will they be affected by this?

They’re in big trouble.

Q: Can’t they resist, or co-opt the blockchain technology in some way?

They’re trying both approaches, and I think there’s probably going to be a market for either of these strategies.

There will be people who just don’t trust this technology and want to raise capital in the old school way, and the legacy banks will likely keep a franchise in that area. But I think trying to co-opt this is really the dominant

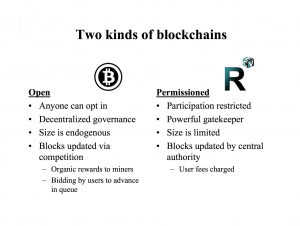

strategy that all the big banks are currently trying to engage in. What they’re trying to do is change the model and impose what is sometimes called the permissioned model, where there’s a blockchain, but it’s a blockchain with a gatekeeper. Not surprisingly, the gatekeeper is the old bank, who controls access and controls who can see the data.

I think the permissioned model is not going to work in the long run, because you are really surrendering many of the advantages of decentralized processing and rapid order execution. It may be a way for these guys to defend their markets for a period of time, but in the long run I think other people who embrace the decentralized open model would be able to undercut them on price and be able to offer services that the permissioned model just doesn’t.

It will be interesting to see how this competition unfolds. I would expect that you’re going to see a lot of consolidation of the banking industry: banks are going to shrink and merge with each other to try to preserve what they can from the franchises they have.

Q: How is this going to affect the business of banking?

Let’s talk about foreign exchange: banks currently make a huge profit marking up international fund transfers. If I want to send money from Zurich to New York, two of biggest banking centers in the world, it’s going to take me 3 days, cost me a 7 percent spread, involve a whole bunch of banks transmitting money along the way, validating it and so forth. What you can do in the blockchain is accomplish that transfer instantly, at almost no cost.

People are now starting foreign remittance services using blockchain technology to try to peel that business off of the banks, and they’ll do this one product line after another, leaving the banks with the things that they lose money on. On the other hand, the banks themselves will start doing their international transfers on this technology. There’s a group in New York called R3 that is a consortium of more than 70 banks trying to create the infrastructure for this. I think banks realize they can’t keep using SWIFT codes and the old system, because it’s so expensive and susceptible to fraud. The Blockchain just offers a much better solution.

So you’re going to see banks migrating this one product line to the blockchain, and at the same time facing outside competitors who are also doing this. The end result is that what used to be a very profitable business for them will disappear. This will happen in auto loans and other areas—every way that banks are making money, you’re going to see people undercutting them using the blockchain.

When their profits shrink, the only way for them to cut costs is going to be economies of scale, so you’re going to see defensive mergers.

It’s interesting to look at the banks’ headcount forecasts, who they’re hiring and how many people they think are going to be on their staffs in five years. Almost every bank is already shrinking and believes it’s going to be shrinking more. This is partly due to Dodd-Frank, but also partly due to them recognizing that this technology is going to begin assaulting the areas where they make money.

One more thing to take into account is that most of the major banks in the world are almost insolvent, and that has been the case since 2008. There are a lot of banks that barely have enough capital to meet the regulatory minimums. For them to get out and raise new money to invest in future technologies is a tough proposition. The only real resources most banks have are the vague promises of government bailouts. So they are really vulnerable to disruption by entrepreneurs.

The other channel of threat is going to be from companies like Google, Apple, Amazon, the technology companies that really do have the money. Many of them are moving rather quickly into financial services. Even Walmart and the telecom companies are applying for banking licenses.

Q: Don’t banks have an advantage, though, in establishing themselves as a gatekeeper?

Most of the financial companies in the world today have failed over the last decade, some of them multiple times. Without abundant government support, it’s hard to see how they are going to be able to remain in business. They’ve mismanaged themselves so badly that I don’t think they have much of an advantage in anything.

There was an event that took place recently, where a company called Overstock.com issued the first-ever equity securities on a private blockchain. They bypassed the stock exchange, registered with the SEC, and then just opened their own blockchain, where you can buy stock from them directly on a peer-to-peer basis.

To me, that’s what the future looks like. When people who are under the age of 30 today get old enough to invest, it’s not obvious they are going to be interested in the NASDAQ or the New York Stock Exchange. But they are already used to dealing with non-traditional platforms.

Q: Can’t banks use their political clout to gain an advantage?

I think that’s what’s happening, but it’s a very different game. The existing players are trying to co-opt the technology and use their positions, but they won’t be successful, because they’ve been successful at almost nothing in the last 30 years. The banks of the world are in a great deal of disrepute because they’ve mismanaged their balance sheets so badly, and I don’t think there’s a lot of public confidence in them. See how many banks are being sued or investigated in this country alone.

Q: Would you say that the emergence of blockchain technology is catching banks at the worst possible time, in terms of their public image, political clout, and financial resources?

One of the things that has made blockchains successful is that the technology rolled out in early 2009, which was the very bottom of the financial crisis, so there was a lot of interest from the tech community and the world at large in looking at alternatives. With the exception of the U.S. and a couple of other countries, the world has been pretty slow to recapitalize the financial system. The banks that exist today are really quite hamstrung for resources and in a great deal of public disrepute. Frankly, I think that these problems are going to get worse, especially because of the problems in Europe—we had the Greek crisis which is now the Italy crisis, and right around the corner is maybe the French crisis. A lot of these banks are holding assets not really worth what they’re written down at on the balance sheets.

Q: What are the competitive implications of adopting blockchain technology? Is the technology inherently competitive? Or are there dangers of it being dominated by a few players who’ll erect barriers to entry?

That’s a good question. We don’t know the answer to that yet. If you look at some of these large consortiums—R3 is one example, the big four accounting firms also have a blockchain interest group—it may in fact become a barrier to entry with a big first-mover advantage. On the other hand, it may be an open source thing which lowers barriers to capital raising and allows everybody to enter the market at a very low cost.

To me this is one of the more interesting questions: does the first mover advantage count for a lot here? We don’t know yet, but competition authorities should really be keeping their eye on this.