A Stigler Center panel explores the implications of big data for competition policy and for consumer welfare.

The business model at the heart of the digital economy is a simple one: Internet giants such as Google and Facebook provide consumers with “free” services—free email, free GPS, free instant messaging, free search—and in return consumers consent to hand over vast amounts of their own data, which the companies then use to target advertisers.

This exchange helped make data the “new” oil, creating “new infrastructure, new businesses, new monopolies, new politics and—crucially—new economics,” according to The Economist. To a large degree, it has also benefited consumers, though as antitrust lawyer Gary Reback noted during the Stigler Center’s conference on concentration in America in March, the services provided by digital platforms are far from free: “You tell your search engine stuff you wouldn’t tell your spouse. You want a really sobering experience? Log in to Google and they’ll show you your last seven years of searches. How would you like it if I put that up on the screen? That’s what you’ve sold to get the service.”

Nor is it an absolute certainty that consumers will always benefit from this arrangement. In their 2016 book Virtual Competition (Harvard University Press), Ariel Ezrachi and Maurice Stucke explore the economic power of digital platforms, and its implications for welfare and society. Big data, algorithms, and artificial intelligence, they argue, can all be used to potentially harm competition and consumers. Big data and analytics could lead to “near perfect” price discrimination. They could also lead to behavioral discrimination: Firms that harvest users’ personal data could tailor their advertising and marketing to target them at critical moments, “with the right price and emotional pitch.” Super-platforms, like Google, can potentially exclude or hinder independent apps and favor their own rival services. A prominent search engine could even, conceivably, have the incentive and ability to degrade the quality of its search results.

As users increasingly rely on super-platforms, and as new forms of extracting, analyzing, and monetizing data develop, the question remains: Will the collection of consumer data by digital platforms ultimately expand choice and empower consumers, or will it be used to diminish consumer surplus?

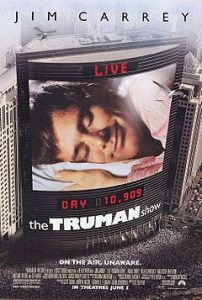

At a panel during the Stigler Center conference on concentration that focused on this very question, Ezrachi compared the new market environment to the 1998 film The Truman Show: a controlled environment that may appear normal and even make its subjects happy, but is nothing more than a façade whose main beneficiaries are the people who control the ecosystem.

“The invisible hand of competition,” Ezrachi argued, has been replaced by a “digitized hand,” controlled and “easily manipulated” by corporations. “It looks very much like what you will see when you go to a market, and yet it can be changed by a few clicks. It can be manipulated. In essence, it brings us to the Truman Show: a reality where everything looks wonderful, [where] you will have the opportunity to live a quite comfortable life, but the one that actually generates the value, the one that benefits from it, is whomever controls the little bubble that was created for you.”’

In addition to Ezrachi, the Slaughter and May Professor of Competition Law at the University of Oxford, the panel featured Tommaso Valletti, the European Commission’s Chief Competition Economist; Michele Polo, Economics Professor at Bocconi University; Frank Pasquale, Professor of Law at the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law and author of The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms That Control Money and Information (Harvard University Press, 2015); and Jonathan Taplin, Director Emeritus of the Annenberg Innovation Lab at the University of Southern California, author of the new book Move Fast and Break Things: How Facebook, Google, and Amazon Cornered Culture and Undermined Democracy (Little, Brown, 2017). The panel, moderated by journalist David Dayen, focused on the implications of big data for competition policy and consumer welfare.

Ezrachi, whose recent work with Stucke explores the changing nature of competition and the increased concentration among digital platforms, surveyed the limits of competition law in the age of big data and algorithmic pricing tools. “The markets that we have today, the markets where we see competition, are radically different than what we believe. We have the façade of competition,” he said. Later, he added: “What we have is literally a market where everything tilts in favor of the dominant.”

Does big data benefit or entrap consumers?

Much of the panel revolved around the question whether the collection of consumer data by online platforms empowers consumers. Ezrachi cited discriminatory pricing and behavioral discrimination as two ways in which big data can potentially be used to harm consumers. “Today almost all the prices that you see online are actually designed for you. Dynamic pricing is the art of squeezing every dollar out of your pocket.”

He added: “This is not science fiction, this is something that already happens today. You have companies that offer these services—building a profile, understanding what are your outside options, what is your willingness to pay once I captured you. I invest in you to capture and acquire you as a customer. Everything that follows will be me charging you more. If I get it wrong, I can always push a coupon in order to basically draw you back to me.”

Despite the promise of competition, Ezrachi said, “many of us, in many markets, [are] actually being lured to purchase things that we don’t necessarily need at prices that are higher.” The new dynamic of competition, he said, has created “gatekeepers we willingly accept.” Those gatekeepers, he added, “once they feel comfortable using advanced data and technology, trying to approximate our reservation price, our willingness to pay, [are] actually starting to increase the price.”

“If you want, run an experiment this evening. Instead of using your MacBook, use a PC, you will get a cheaper price. Leave your house, go to a different house, book the same holiday or buy the same product, you will get a cheaper price. Never go directly to your favorite site. Always go through Google. Even the simplest dynamic pricing will give you a discount if you came from a marketplace,” Ezrachi said.

Ezrachi then discussed what he called the “next phase”: the fledgling area of personal digital assistants, such as Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa, or Facebook’s M. Last year, in a paper he co-wrote with Stucke, the two argued that reliance on super-platforms through the growing use of personal digital “butlers” could, in the future, potentially intellectually capture users, as consumers increasingly distance themselves from “the junctions of decision-making” and put their trust in platforms.

“Your personal butler will anticipate your needs. It will actually be empowered by AI and able to communicate with you in a manner which is just exactly what you need, with just enough humor in order for you to feel comfortable with it, just enough information to really help you through the day. That’s the promise, that from ordering our cab in the morning to ordering Chinese in the evening, or asking for some articles, this will be the interface,” Ezrachi said. The danger, he argued, is that “you are basically willingly capturing yourself and willing to be part of this ecosystem that is controlled by one single gatekeeper.”

This possible future, said Ezrachi, creates a “universe where switching costs are immense because you have a butler that already has all the information about you. It is very expensive to train your new butler. It is actually impossible to transfer information, the majority of it, due to IP issues and some technical issues.”

This, he maintained, leads to “fierce competition” between the leading platforms over who can achieve first-mover advantage. “The first one to enter your living room is the one to control you.”

In contrast with Ezrachi and the other speakers, Polo took a more conservative approach, extolling the benefits of big data for consumers, such as reducing search costs and increased participation in markets. However, he added, “if we just look at consumer surplus in a very narrow, traditional way, we are missing something of the big picture.” Firms, he said, “realize that being sampled first, what is called in jargon being prominent, pays in terms of profits and larger sales. That there is a premium for dominance.”

“Differentiation through platforms,” Polo noted, “tends to limit the ability to dominate an entire single market. At the same time, we have different separate gigantic platforms, each one delivering possibly services that are not the same.” On price discrimination, he added: “As economists, we are cautious to have a negative view of price discrimination in general. A case by case analysis is needed.”

Pasquale, whose book explores the effects of “black box” algorithms on privacy, regulation, and society, discussed the issues of choice and switching costs. “In classic economic theory, the ideal response is ‘When they start acting against your interests, choose another service.’ The first response to that is, of course, the ‘who knows’ black box problem that I talked about in my book: We do not all have the time, energy, ability, skills, etc. to be continually running different computer programs in the background and various searches to see if we got the best results that we should have.”

He continued: “The second problem here is that even if I were to switch, we have to understand that the consequences of the switch could quite easily be service degradation. I have, in a way, created a partnership with Google over 10 years of searches. They have literally tens of thousands of emails from me, thousands of points of search data. If I were to suddenly switch to Yahoo or to Bing, that is a massive loss for me because Yahoo and Bing don’t have that data. I can’t easily export that data. That, to me, shows a fundamental flaw in so much of the economics literature, in that it tries to model a unitary consumer switching. People are in very different circumstances if, for example, they used Google for five years intensively, or if they have cultivated a, say, diverse array of search engines that they use.

“Another classic economic response is ‘you should have negotiated better. Why didn’t you write a letter to Facebook and say, ‘Dear Facebook, I would like to pay you $5 a month so you don’t keep a profile of my health information. I’d really like to be able to talk to my friends on Facebook and tell them that I have cancer and not be afraid that the data is going to be sold to some company that’s going to sell it to my employer and say ‘Don’t hire this person because you’ve got a self-funded health plan and he may be a huge cost to you in the future.’ I’d like to be able to do that. I can’t do that. If I sent that letter to Facebook, they’d laugh at me.”

Both Taplin and Ezrachi went on to discuss the deep impact of digital platforms’ economic power in regards to the marketplace of ideas, as 62 percent of Americans now get their news from social media. “In the spring of 2016, Fox News, Breitbart, and a lot of people pushed very hard against Facebook, saying that the humans involved in the Trending Topics part of Facebook were skewing the content towards liberals and towards liberal views,” said Taplin. “Under all this pressure, Facebook said, “OK, we’ll take the humans out of it and just let the algorithm decide what the trending topics are.” This, he argued, allowed the fake news business to flourish and potentially influence the election.

Spreaders of fake news “were able to game the system, using Russian bots and other things, to bomb the algorithm in such a way that the fake news business took off and the real news business declined,” said Taplin. “The combination of Facebook and a Google AdSense account was capable of making a kid in Macedonia $5,000 to $10,000 a week putting out fake news. That is something that could’ve never existed without this big data, platform-agnostic situation that we find ourselves in.”

Antitrust in the age of big data

Last week, the European Commission handed Facebook a €110 million fine for providing it with “incorrect or misleading information” regarding the social media giant’s acquisition of WhatsApp. When Facebook purchased WhatsApp in 2014, the EC alleged, it told the commission that it would not be able to match users’ accounts between its platform and WhatsApp’s. The merger was cleared, and Facebook and WhatsApp proceeded to do just that. EC officials later found out that Facebook knew that this matching was technically possible back in 2014.

In part, the fine reflected the growing concerns of European regulators over privacy and the competitive implications of the digital platforms’ collection of consumer data. It also reflected the difficulties competition authorities face in adapting to the dynamics of the “digitized hand.” In an interview with the Financial Times last week, following the Facebook fine, the EU’s Competition Commissioner Margrethe Vestager acknowledged that “The competition rules weren’t written with big data in mind. But the issues that concern us haven’t changed.” In a speech in September, Vestager said that “The future of big data is not just about technology, It’s about things like data protection, consumer rights and competition.”

Valletti, who is also a Professor of Economics at the Imperial College Business School and the University of Rome Tor Vergata, discussed the EC’s investigation into the Facebook-WhatsApp merger during the panel. Facebook, he said, had “lied” to European regulators about its ability to absorb WhatsApp’s user data, but the larger issue was market definition.

“Would the decision on the merger have changed had the Commission known that information at the time?” asked Valletti, who joined the EC in 2016. “At the time, the Commission defined the relevant market as non-search advertising. This is a huge market. In that ocean, even Facebook doesn’t have a lot of market power. If instead the market definition had been, for instance, advertising on social networks, [it’s] likely they would have concluded that Facebook would have been dominant in that particular market, and that integrating that useful information from [WhatsApp] could have enhanced its market power.” Valletti also stressed the importance of having individual-level data when discussing issues like competition at the advertising market, and not just looking at market shares.

Pasquale and Taplin, meanwhile, criticized U.S. antitrust authorities, with Taplin saying that digital platforms have “done very well because they have a certain regulatory capture” and Pasquale remarking that “U.S. antitrust policy is rapidly becoming a pro-trust policy.”

As an example of this “pro-trust” policy, Pasquale cited the FTC’s lawsuit against online contact lens retailer 1-800 Contacts. 1-800 Contacts was sued by the FTC last year for having reached agreements with 14 other online contact lens sellers that they would not advertise to customers who had searched for 1-800 Contacts online. “You would imagine that given the power of these [companies], and given the activity in Europe and many other nations, our enforcers would be extremely concerned about these platforms. They are—they’re concerned about little companies hurting the platforms,” he said.

The FTC, added Pasquale, had pursued the 1-800 Contacts case aggressively. “I’m not here to comment on the merits of this case, but I think that the choice of this enforcement target speaks volumes. What does it say? It says that if small firms are being exploited or hurt by a big digital behemoth, or think [they] are, don’t try in any way to coordinate or maintain your independence. What you should do is all combine and merge and become a giant, say, contacts firm. In the media, they should all combine and merge and maybe all be bought by Comcast, so that then they can negotiate with Google in a way that they are relatively of the same size and power. That’s the pro-trust message we’re getting under current non-enforcement U.S. antitrust policy.”