In order to get optimal regulation in the financial world, says Alan Blinder, the former Vice Chair of the Federal Reserve, one should seek to over-regulate.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO), a U.S. Government agency that provides investigative services to Congress, was tasked last October with a new mission: to investigate whether the Federal Reserve and other regulators are too soft on the banks they are meant to police. Lawrance Evans, the GAO’s director of Financial Markets, recently told Reuters that the agency will conduct “an assessment across all financial regulators, and the Federal Reserve will be one institution.”((Jonathan Spicer. 2016 “Exclusive: U.S. watchdog to probe Fed’s lax oversight of Wall Street.”))

Regulators, academics, bankers, and experts will be called to offer advice and share their experiences. But perhaps the best first step for the investigative team of the GAO is to turn to history – to 1982, when George Stigler received the Nobel Prize for his theory of regulation. In his seminal piece, inspired by earlier scholars like Mancur Olson, Gordon Tullock, James Buchanan, and many more, he explained the dynamics that lead most regulators to be acquired by the industry they are tasked with regulating.

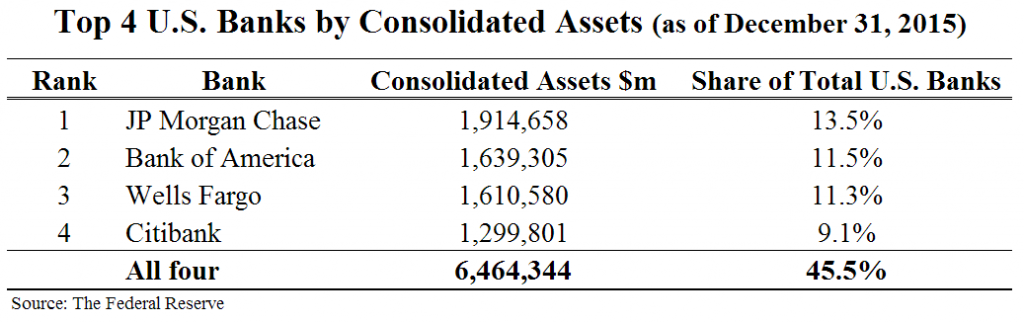

When a small group that has a concentrated interest competes with a dispersed large group, it is the former and not the latter that usually wins. One cannot think of a better example than the U.S. banking system in 2016: four banks control 45.5 percent of the market, $6.5 trillion in consolidated assets((Federal Reserve Statistical Release: Insured U.S.-Chartered Commercial Banks That Have Consolidated Assets of $300 Million or More, Ranked by Consolidated Assets (As of December 31, 2015).)). Banks spend hundreds of millions of dollars every year((OpenSecrets.org)) on lobbying and campaign contributions, and have close ties with academia and experts((Admati, Anat. 2016. Forthcoming.)).

The ideas of Stigler and Olson can be interpreted in two directions. The first, taken usually by the “public choice” school of academics, is that the less regulation we have, the less opportunities for captured regulation and rent-seeking. The second direction is a more nuanced one: regulation tends to be captured, therefore we need simple((Zingales, Luigi. 2012. “A Capitalism for the People: Recapturing the Lost Genius of American Prosperity.” Basic Books.)), aggressive regulation that cannot be easily captured((Carpenter, Daniel and David A. Moss (Editors). 2013. “Preventing Regulatory Capture: Special Interest Influence and How to Limit it.” Cambridge University Press)), or to create conditions for effective competition.

While in many industries reducing regulation and simplifying it is theoretically an attainable task, in the financial system it’s a much taller order; financial systems are prone to booms and busts, can have dramatic spillovers to the rest of the economy and, in failures, can take a dramatic toll on taxpayer money.

Professor Alan Blinder, former Vice Chairman of the Federal Reserve (June 1994 to January 1996), has been studying the financial system for close to 30 years. In 2014 he published a paper that did not get enough attention, but that students of regulation theory may find surprising: In order to get optimal regulation in the financial world, one should seek to over-regulate.((Blinder, Alan S. 2014. “Financial Entropy and the Optimality of Over-Regulation.” Griswold Center for Economic Policy Studies, Working Paper No. 242))

The idea of cyclical regulatory equilibrium in financial markets is not new, as Blinder immediately admits. In a 2009 paper, Joshua Aizenman wrote that “prudential” under-regulation may expose economies to future financial crises, which means that over-regulation may be the correct course((Aizenman, Joshua. 2009. “Financial Crisis and the Paradox of Under- and Over-Regulation.” NBER Working Paper No. 15018)). And, of course, Blinder also borrows from the “Minsky cycle”: Hyman Minsky’s idea that periods of financial stability encourage further and further risk-taking, even with borrowed money, until a phase–a “Minsky moment”–where asset values collapse.

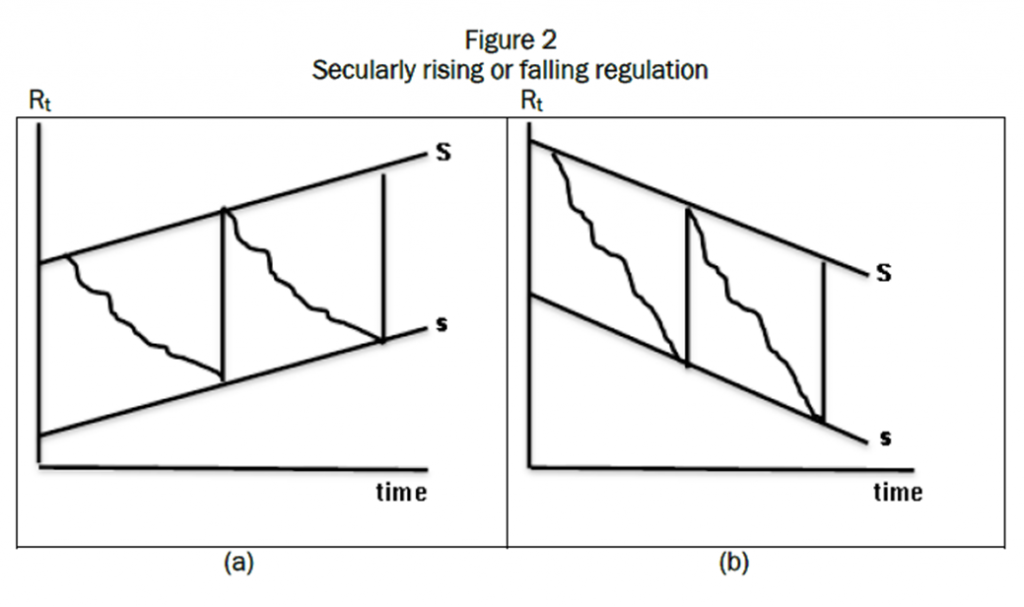

“Financial regulations and their effectiveness tend to get weakened over time by (a) industry workarounds, (b) regulatory changes, and (c) legislative changes. The main exceptions come during and after financial crises or scandals, when public revulsion against financial excesses enables, perhaps even forces, a tightening of regulation,” Blinder writes.

Therefore, in Blinder’s view, over-regulation, when it can be achieved, is actually optimal. Or, in his words: “a simple, but not mathematically accurate, way of thinking about the optimality of over-regulation is that it gets the degree of regulation ‘right on average’ over time.”

This constant movement of regulation towards the int

erests of the financial industry leads Blinder to prescribe over-regulation in those rare instances where there is political will and ability to regulate.

Guy Rolnik: You’ve been around in the financial sector for many years, and specifically in regulation, and then you come up with a simple idea: we have to over-regulate as an objective.

Alan Blinder: Yes. The key point there is that you over-regulate when you get the chance because you know, or you should know, that the severity of the regulation is going to dwindle thereafter. That’s what I call the financial entropy theorem.

GR: Looking at history, what are the events when you do have the chance to regulate?

AB: I think to a first approximation, and it’s a very good approximation, you only get a chance when there’s some kind of a crisis. So, for example, we had in 2008-9 a very serious financial crisis, followed by Dodd-Frank in 2010.

We had in the early ’90s the savings and loan calamity, followed by very substantial regulation. The tradition is that you try to either solve or mitigate the problems that have just smacked you in the face.

One further point: If you go to Congress and nothing terrible has happened and say ‘there are dangers lurking here, and maybe we should do something about it in a regulatory way,’ you’re not likely to succeed.

GR: This flies in the face of the idea that this may lead to unintended consequences.

AB: No, every regulation has unintended consequences. That’s not an issue. But I would say it’s only at those rare instances that you get to regulate, certainly in the financial context.

I’m not so worried about regulation going overboard for two reasons. One, which we already talked about, is that there is financial entropy that will reduce the bite of the regulation over time.

The second, however, is that even in real time the industry has lots of lobbyists to protect it from the most excessive and egregious over-reaches.

GR: And you are not worried about the possible unintended consequences of such regulation?

AB: Not too much. The only one thing I think I want to add to your sentence is the adjective, “financial.”

For example, I can imagine that, in health regulation, one could make mistakes that actually make people sicker or even kill people. Let’s put it this way, I drew these generalizations only for financial regulations. I wouldn’t just blithely apply them to all regulations.

GR: But some of the ideas that you present would also be very relevant to most.

AB: I think that’s right. You have to just consider those others on a case-by-case basis.

I also want to add that regulatory entropy is probably an even more important observation where the regulations are detailed and complex, as opposed to when they’re big, broad, and general–and get a lot of public attention.

If we imagine, for example, and I’m getting fanciful here, a cap and trade system as a remedy for global warming. If we ever got serious about it, I think that it would be in the headlines. It would include a tax or something like that.

A lot of people would know about it, and it would be much less in the shadows. Whereas in financial regulation, if you stop the average American in the street now, or even in the summer of 2010 when it was being legislated, and said “name one thing that’s in Dodd-Frank,” I don’t think one in a thousand could give you an answer.

GR: Yes. I bet that many economists don’t know what’s really in those 2,300 pages.

AB: Well, almost no one except the lawyers and lobbyists know what’s in the whole 2,300 pages. But as a broad generalization, the populace probably knows nothing that’s in it.

To some extent I think that’s important.

GR: You’re saying that one of the ways to deal with regulatory capture is to understand the mechanics and the equilibrium and that this is why many times we have to over-regulate.

AB: Yes, exactly that. When I elucidated the reasons for the financial entropy theorem, for the withering away of the effect of regulations, the first thing on my list was the actions of the regulators themselves easing the burdens by detailed rulings and slight modifications of the regulations or enforcement.

GR: Let’s go back 20 years. What would you have said then if I presented you with this idea that over-regulation is a way to solve captured regulation in the banking sector?

GR: Let’s go back 20 years. What would you have said then if I presented you with this idea that over-regulation is a way to solve captured regulation in the banking sector?

AB: I don’t think I would have said anything like this when I was Vice Chair of the Fed. It takes years of watching these processes unfold, I think, to appreciate that. Furthermore, remember those were the Greenspan years. I wouldn’t have had the perspicacity to voice something like that at the Fed then. Besides, if I did, it would have been laughed out of court.

GR: So maybe what is needed here is three things. First of all, in order to understand this dynamic that you describe here, you have to have a very long perspective, because you have to see those cycles going on a few times. You also have to be an insider in a very important regulatory body, and you have to be an economist.

AB: Probably. I’m not sure you have to be an insider in an important regulated body. You could be an external student of financial regulation who watches things closely without serving in the government. I think that’s certainly possible.

GR: Is there a specific point in time where you started developing this idea? Was it during the last financial crisis? Before the crisis? After the crisis?

AB: I think it was mostly after the financial crisis, because to tell you an important truth, one of the things that really put this framework into my mind was Minsky. Minsky was not mostly about financial regulation, but his ideas were a little about financial regulation. What it was mostly about was cycles of forgetting and remembering financ

ial excesses.

A key ingredient in the financial entropy theorem is the notion that, while the good times are rolling, everybody forgets about the bad times, and the danger is that we may lapse back from the good times to the bad times. That’s a major reason why the regulatory burden lightens.

That’s really a Minskyan idea. Like most economists, Minsky never appeared in my training, nor, I must confess, did he appear in my teaching. It was only after the crisis that I started thinking about Minsky, as many people did.

GR: The problem with the financial sector is not only its riskiness but its sheer size. Maybe half of the industry is what you call rent-seeking–activities that don’t serve the allocation of resources and social causes.

AB: Yes, I think that’s right—or potentially right, anyway. If you think about modern financial innovation, fancy financial products like derivatives, and I’m talking especially about over-the-counter customized derivatives, one of the things they’re about is making competition extremely difficult because buyers can’t do comparative shopping for the best price. So complex instruments raise the returns of the financial companies that create them.

I think everybody knows that, especially the people that create them. That does not look like a productive activity to me.

GR: How often do we see situations in financial markets where competition doesn’t weed out low-quality players?

AB: I’ll give you an example that everybody knows about, which is health insurance plans. One of the reasons for the malfunctioning of the health insurance system is that the differences are so many and so complicated that it was very hard for consumers to put them side by side and say, “This is a better deal. This is a worse deal.”

GR: How will competition work in financial markets?

AB: It works very well for the kind of textbook model that we teach in elementary economics, which is a market for a homogeneous product sold by many small competitors; information is symmetric rather than asymmetric (so the buyer knows what the seller knows); and a variety of other things. Under those circumstances, competition works beautifully.

GR: But the problem is that these circumstances are very rare in the real marketplace.

AB: Yes, I think maybe the best way to put this is not the way I put it in the paper: It doesn’t work so well with complicated goods and services. It works very well with simple goods and services.

GR: Yes, and by the way, how often do we teach that to our students?

AB: Hardly ever.

GR: Let’s say you do a BA, MA, and PhD in economics. How much do you get in each step?

AB: I think that if you do your BA you get a little bit. One particular instance of this is asymmetric information that I mentioned before, where the seller knows more than the buyer. A little of that creeps into undergraduate curricula, there’s a lot of it in graduate curricula, a lot.

That’s pretty well understood. But I don’t know that we have much about the complexity issue, especially where it’s contrived complexity.

GR: Is it possible that the financial industry is promoting this complexity in order to capture regulation?

AB: Yes.

GR: Going back to your paper, most of the time we are not in the situation where we can regulate because time has passed from the crisis.

AB: Yes.

GR: So we’re not very hopeful about the ability of regulators to act at this point after reading your paper.

AB: I think that’s right. The balance of lobbying power is extremely skewed between the industry and the consumers.

GR: Is it only the balance of lobbying power, or is it also the case of such a huge industry with so much resources and influence?

AB: That’s what I mean. I also want to say lobbying power. It also flows into what you were saying before about Stiglerian capture.

GR: About intellectual capture of the regulators?

AB: Yes. I think it’s basically cognitive capture.

GR: More than the revolving doors between the regulating agencies and the regulated industries?

AB: I think so, although the revolving door is relevant also. I don’t think it’s either outright or tacit bribery, not very often.

You do hear cases of dishonesty and things like that, but I really think in the US that’s a trivial part of the problem compared to, say, cognitive capture.

GR: We’re not talking about illegal stuff, but about cases where regulators know that, when they cross over to their formerly regulated corporations, their salaries will be 10, 20, or 50 times higher. Doesn’t this also create some kind of a social capture?

AB: Yes, a little. It’s hard to make that analysis quantitative, like how important it is. I’m sure there’s some of that. Let me come back and add one more thing. If you are a big banker, and you want to hire a former regulator into your company, what you’re really after is not how soft he or she was as a regulator. In fact, there’s a sense in which a tougher one might be better for the company, because what you’re really after is someone who can guide you through the ins and out of regulation. So what is it that an incumbent regulator really has to do? You see what I’m getting at?

GR: Yes.

AB: It’s not like you want to hire the guy who, while he was in the regulatory agency, was salivating about going to work for an investment bank and doing everything he could do to ingratiate himself, because that’s not going to help you as, say, the CEO of the business. You want to bring knowledge in so that you can cope with the system better.

GR: Yes, maybe it’s more complex than that, because you want people that are very smart. You may want regulators that gave you a hard time.

But, on the other hand, I’m not sure that it creates an incentive for the regulator to do a better regulatory job, such as something that will address rent-seeking, for instance.

AB: Yes, it’s hard to take that kind of a long perspective for anybody.

GR: When you talk about capture, you say that they are the masters of the universe because, after all, they earn so much. Maybe this has to do with cognitive capture–the belief that if someone is making 10 times, 20 times, or 100 times more money than the regulators, that person must be very smart and we should all listen to them.

AB: I think that’s commonly believed. You know the old line from Fiddler on the Roof: “When you’re rich they think you really know.” There’s wisdom in that. People do act that way.

GR: We did not talk about the long term. When you want to solve this problem that you describe here, what can we do to diminish the huge political and social power of huge industries over regulation?

AB: I think it’s very difficult. First of all, what seems obvious is to diminish the influence of lobbyists. That seems obvious, but then when you read the U.S. Constitution, not to mention the zillions of court rulings based on it, you realize how difficult it is.

Lobbying is a protected constitutional right. Bribery is illegal, but lobbying is completely legal and constitutionally protected. It’s very, very, very, very difficult to do limit it.

Similarly, the next line of defense is the Congress. The simple prescription is to elect better congressmen and women. Easier said than done. The third, I think, which is doable, is that a president puts skilled, smart, and tough-minded regulators into the offices of the heads of the regulatory agencies.

That doesn’t mean regulators who are out to decimate the industry, but regulators that understand that their role is to protect the people that need protection, and that’s probably not the financial giants.

GR: That hasn’t happened for a while.

AB: It does and it doesn’t. But if I look at it in that light I would say that the message is over-regulate when you’ve got the opportunity, and don’t be shy.

GR: When you say over-regulate, do you also mean go for measures like breaking the banks in order to make sure that they don’t have such political power? Going back to the original antitrust, it was invented way before economic analyses as a political tool to make sure that nobody accumulates too much power.

AB: Yes, I think there’s something to that. It’s not the usual argument that is made, although it is one of the arguments that is made. A problem with that, which you’ve heard, for example, and I’ve heard Barney Frank bring this up a number of times in the context of Bernie Sanders’ claims, is how big is too big?

I mean, it’s easy to say they should be smaller. How much smaller? Let me be concrete. Example, JPMorgan Chase is now about a two-and-a-quarter trillion-dollar company by assets. Would there be less power there if it was one and an eighth trillion dollar company? That’s not obvious to me.

GR: Probably not.

AB: In fact, it could go the other way around, with two such companies. Now, if you’d say, OK, now we don’t want any bank bigger than two billion, so that none of them is going to have political power. But then we will not have an industry capable of serving the needs of commerce.

When you start talking about breaking up the banks just because of size, numbers matter a lot. It’s not obvious to where you look for guidance about what’s the right number.

GR: So what is your solution?

AB: First of all, I don’t have a solution. Second, it’s the obvious things I said before: better regulators, better politicians. The only thing that I would add to that is sunshine, more exposés by journalists, for example.

GR: I can tell you all about the ability of the media to operate, like going after banks, when you have only four banks in the country and most of the media is controlled directly or indirectly by people who need favors from banks.

AB: Yeah, but there’s a couple of slippages between cup and lip there by the time you get down to the level of the reporter. What you just said is a potential problem, but I think the bigger problem is the kind of technical expertise you need to get inside some of these issues.

GR: The experts usually prefer to work for the banks and not for the media.

AB: Not for the media. That’s right, and it’s pretty tough for the reporter who next month is going be writing a story on the military, or on an obituary of Prince or something, to dig into the details of Dodd-Frank, or some pending legislation.

GR: Did you get any pushback on this paper?

AB: You know, I would say I got very little attention, period. This is part of what happens when you publish things, first of all, in obscure conference volumes in general, and then, within the economics profession, when you publish things that don’t have any math.

So probably very few of my professional economics colleagues have read this piece or even know about it.