The Chinese government has invested heavily in surveillance systems that exploit information on social media. This column shows that these systems are very effective, even in their simplest form. From the government’s point of view, social media, although unattractive as a potential outlet for organised social protest, is useful as a method to surveil protests, monitor local officials, and disseminate propaganda.

[Editors’ Note: This post first appeared at VoxEU.org with the title “E-autocracy: Surveillance and propaganda in Chinese social media.”]

Behind closed doors, firms and politicians increasingly mine social media data for political purposes. Several recent events, including the Cambridge Analytica scandal, corroborate this and have triggered worldwide discussion on whether social media undermines the functioning of democracy. Closely related to this discussion is the heated debate regarding the role of social media in non-democracies. Inspired by the Arab Spring and numerous anecdotal stories of how corrupt officials were brought down by public discussion on social media, some scholars (e.g. Shirky 2011) believe that social media plays a role in holding authoritarian governments accountable. While authoritarian regimes may defensively censor social media to curtail such outcomes,((See Bamman et al. (2012), Chen and Ang (2011), Fu et al. (2013), King et al. (2013, 2014), and Zhu et al. (2013).)) they cannot turn them completely in their favour. Enikolopov et al. (2016) provide evidence in support of this view. In contrast, others (e.g. Morozov 2012, Lorentzen 2014) argue that an authoritarian government can even can increase regime stability and enhance power by exploiting social media for surveillance and propaganda. These regimes are obviously well informed about the scope and effectiveness of these strategies, whereas the public is left in the dark.

To bring this to light, in a recent study (Qin et al. 2017a, 2017b), we provided the first large-scale evidence on the effort and effectiveness of building an e-autocracy through social media. In particular, we examine the effectiveness of surveillance and the extent of propaganda in China’s social media. Our study is based on a dataset of 13.2 billion blog posts published on Sina Weibo – the most prominent Chinese micro blogging platform – over the period 2009-2013.

Surveillance of protests and corruption

Result 1: Protests and strikes can be predicted by social media content, one day in advance, with excellent accuracy

We analysed 545 large collective action events that took place in mainland China between 2009 and 2012. Using a simple method based on keyword counts, we predicted these events. We evaluated our prediction using AUROC, a popular measure for the accuracy of a model’s predictive ability.((AUROC measures the area under the ROC curve. A ROC curve shows the tradeoff between type 1 and type 2 errors in prediction and was first employed in WWII to evaluate methods that analysed radio signals used to identify Japanese aircrafts for example. The reported AUROC is based on Figure 2 in Qin et al. (2017b).)) The surveillance tool we developed had an AUROC of 0.87 for predicting strikes and 0.96 for predicting anti-Japan events, close to or above the threshold of 0.9, which is typically viewed as excellent.

This is likely a lower bound on the accuracy of the actual systems being used for surveillance by Chinese government agencies, as they have invested heavily in building machine-learning surveillance systems that exploit information on social media. Conversely, the accuracy of surveillance methods can be impaired if protesters aware of surveillance remain silent. However, our study shows that posts predicting protests are often neither created by protesters nor explicitly about the predicted protests. Instead, a large number of posts are published by bystanders and are indirectly related. These patterns can also be exploited by machine-learning methods.

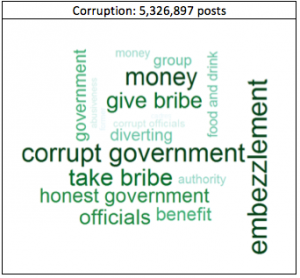

The high prediction accuracy is a consequence of the large volume of relevant posts. We find millions of social media posts discussing collective-action events in our data; some of them precede the events and even explicitly call for participation. In contrast, newspapers are completely silent about these events. We characterise these social media posts by using topic modeling (see Table 1). Similarly, we find an even larger number of social media posts discussing government corruption in our data (see Table 2 for the most popular topics of such posts).

These posts are effective for corruption surveillance, although less informative than in the case of protests. In particular, we analysed 200 corruption cases involving high-rank Chinese government officials. For comparison, we constructed a matched control sample of 480 politicians who held similar political positions but were not charged with corruption. A simple regression model showed that social media posts significantly predicted which politicians were charged with corruption a year later (with poor predictive accuracy however; AUROC below 0.6). The main reason was that only one third of all officials charged with corruption were ever mentioned in a corruption post. This absence of social media discussion suggests that either they managed to fly under the social media radar, or that they were no more corrupt than the comparison officials and were charged for other reasons.

Result 2: Sina Weibo is used extensively for propaganda

In 2012, Sina Weibo reported that government offices and individual officials operated approximately 50,000 accounts. To assess accuracy of this number, we provide the first external estimate of the Chinese government’s presence on social media. We identify government accounts from user names and using textual analysis of the posts in our data. According to this estimation, there are 600,000 government-affiliated accounts, including government organisation, mass organisation, and media users. Government presence was therefore substantially underreported by Sina Weibo. These accounts contribute 4% of all posts regarding political and economic issues on Sina Weibo.

Government accounts may spread neutral information (for example, about health care services) or propaganda. If the dominant motive is political influence via propaganda, then we would expect to see more government users in areas with more extensive censoring and more strongly biased newspapers, because the regime likely uses all means of political influence when the need for such influence is high. Using a popular classification algorithm (support vector machine), we use word frequencies to predict the probability that a user is affiliated with the government. We find that the share of government users is higher in areas with more extensive censoring of social media posts (Bamman et al. 2012) and in areas where newspapers are more compliant with the Party line as measured in Qin et al. (2018) (see Figure 1). This is consistent with political influence being the main motive of the government-affiliated accounts.

Concluding remarks

The Chinese government has invested heavily in surveillance systems that exploit information on social media. Our study shows that these systems are very effective, even in their simplest form. This result implies that political leaders in Beijing are not at risk of being caught off guard, as they can effectively monitor corrupt officials and predict protests in faraway regions using social media, despite the incentive of local leaders to silence this information. Moreover, we find that the government’s presence on social media is considerably larger than officially reported, and its variation across regions is consistent with propaganda being its main purpose. This use of social media for surveillance and propaganda is likely to improve regime stability and power.

Our findings challenge a popular view that an authoritarian regime would relentlessly censor or even ban social media. Instead, the interaction between an authoritarian government and social media seems more complex. From the government’s point of view, social media, although unattractive as a potential outlet for organised social protest, is useful as a method to surveil protests, monitor local officials, and disseminate propaganda. Strict censorship would diminish the value of social media for the purposes of surveillance and propaganda. This is in line with our findings in Qin et al. (2018), in that the extent of propaganda in Chinese newspapers is governed by a trade-off between political control and economic benefits.

References

Bamman, D, B O’Connor, and N Smith (2012), “Censorship and deletion practices in Chinese social media”, First Monday 17(3).

Chen, X and P H Ang (2011), “Internet police in China: Regulation, scope and myths”, in D Herold and P Marolt (eds), Online Society in China: Creating, Celebrating, and Instrumentalising the Online Carnival, Routledge, pp. 40-52.

Egorov, G, S Guriev and K Sonin (2009), “Why resource-poor dictators allow freer media: A theory and evidence from panel data”, American Political Science Review 103(04): 645-668.

Enikolopov, R, A Makarin and M Petrova (2016), “Social media and protest participation: Evidence from Russia”, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Available at SSRN 2696236.

Fu, K, C Chan and M Chau (2013), “Assessing censorship on micro blogs in China: Discriminatory keyword analysis and the real-name registration policy”, Internet Computing, IEEE 17.3: 42-50.

King, G, J Pan and M E Roberts (2013), “How censorship in China allows government criticism but silences collective expression”, American Political Science Review 107(2): 1-18.

King, G, J Pan and M E Roberts (2014), “Reverse-engineering censorship in China: Randomised experimentation and participant observation”, Science345(6199): 1-10.

Lorentzen, P (2014), “China’s strategic censorship”, American Journal of Political Science58(2): 402-414.

Morozov, E (2012), “The net delusion: The dark side of internet freedom,” Public Affairs, 28 February.

Qin, B, D Strömberg and Y Wu (2017a), “Why does China allow freer social media? Protests versus surveillance and propaganda”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 31(1): 117-40.

Qin, B, D Strömberg and Y Wu (2017b), “Why does China allow freer social media? Protests versus surveillance and propaganda”, CEPR Discussion Paper 11778.

Qin, B, D Strömberg and Y Wu (2018), “Media bias in China”, American Economic Review, forthcoming.

Shirky, C (2011), “The political power of social media: Technology, the public sphere, and political change”, Foreign Affairs, January/February.

Zhu, T, D Phipps and A Pridgen (2013), “The velocity of censorship: High-fidelity detection of micro blog post deletions”, arXiv preprint arXiv:1303.0597.

Disclaimer: The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.