Note: The post below was first published at VoxEU.org.

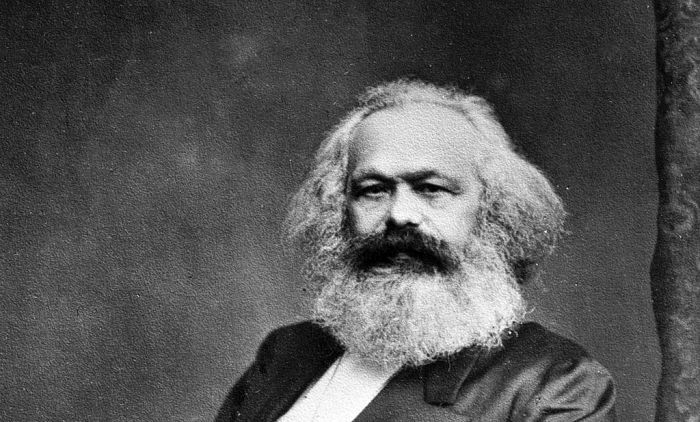

Economists, looking back, have not found much to admire in Karl Marx, the economist, the bicentennial of whose birth we commemorate next month. John Maynard Keynes referred to Capital as “an obsolete economic textbook [that is] not only scientifically erroneous but without interest or application to the modern world” (Keynes 1925). Paul Samuelson’s judgement—“From the viewpoint of pure economic theory, Karl Marx can be regarded as a minor post-Ricardian”—was equally harsh, especially as he thought Ricardo was “the most overrated of economists”(Samuelson 1962).

Economists, looking back, have not found much to admire in Karl Marx, the economist, the bicentennial of whose birth we commemorate next month. John Maynard Keynes referred to Capital as “an obsolete economic textbook [that is] not only scientifically erroneous but without interest or application to the modern world” (Keynes 1925). Paul Samuelson’s judgement—“From the viewpoint of pure economic theory, Karl Marx can be regarded as a minor post-Ricardian”—was equally harsh, especially as he thought Ricardo was “the most overrated of economists”(Samuelson 1962).

These assessments are based largely on our current—and correct in my view—understanding of Marx’s labor theory of value as a pioneering, but inconsistent and outdated, attempt at a general equilibrium model of pricing and distribution. But there is another aspect of his work that has been strongly vindicated by theoretical advances in recent decades: the idea that the exercise of power is an essential aspect of the working of the capitalist economy, even in its idealized, perfectly competitive, state.

Domination in Liberal Society

Marx used the labor theory of value to demonstrate that the exploitation of workers is a necessary condition for profits (Yoshihara 2017). The normative term ‘exploitation’ is justified by the claim that profit arises from a system of domination in which the wealthy, as owners of capital goods, direct the activities and limit the choices of employees (Vrousalis 2013). Domination in this sense could be sustained by an autocratic state acting on behalf of a capitalist class, or through the exercise of market power made possible by limited competition in goods markets.

But Marx chose to study a more challenging question: how could the domination of labor by capital take place in a private, perfectly competitive, economy governed by a liberal state? His answer was based on what seems a strikingly modern principal-agent representation of the employer-employee relationship, arising from a conflict of interest over the amount of labor effort performed that could be resolved in an enforceable contract.

Marx stressed that the employer purchases the worker’s time on the labor market, not the worker’s work. The employee’s supply of effort to the production process is not secured by contract but was rather an “extraction” that “only by misuse could … have been called any kind of exchange at all” (Marx 1939).

To stress the distinctive aspect of the labor market, Marx (1867) pointed out that:

“[T]he rise in … wages may … be unaccompanied by any change in the price of labor [meaning effort], or may even be accompanied by a fall in the latter.”

The important consequence for the worker, “be his payment high or low,” was “domination and exploitation” and “a form of despotism more hateful for its meanness” (ibid).

The final step in Marx’s explanation of domination in a liberal capitalist economy was the process of accumulation and technical change that supports a permanent “reserve army” (ibid) of the unemployed, and which provides the basis of the employer’s labor discipline strategy. The private ownership of the means of production conveys the right to exclude others from use of the firm’s assets, and therefore the owners of firms have a powerful threat to induce workers to supply the effort that could not be secured by contract: work hard, or join the “reserve army.”

The Politics of Production

Marx did not explain why the labor contract was incomplete. He assumed this was an uncontroversial empirical observation and used it as the starting point for his economic theory. In this, he resembles Charles Darwin who advanced a powerful theory of natural selection without an understanding of the mechanism by which it occurred. Genetic inheritance would later be explained by Gregor Mendel.

Just as Mendel underpinned Darwin, a more complete understanding of the incomplete labor contract developed in the twentieth century, but did not overturn Marx’s conclusions. Like Marx, Ronald Coase (1937) stressed the central role of authority in the firm’s contractual relations:

“[N]ote the character of the contract into which a factor enters that is employed within a firm …[T]he factor … for certain remuneration agrees to obey the directions of the entrepreneur.”

Indeed, Coase defined the firm by its political structure:

“If a workman moves from department Y to department X, he does not go because of a change in prices but because he is ordered to do so … the distinguishing mark of the firm is the suppression of the price mechanism.” (ibid)

Herbert Simon provided the first Coasean model of the firm (Simon 1951). He represented the employment contract as an exchange in which the employees transfer control rights over their work tasks to the employer, in return for a wage. Simon stressed the advantage to the employer of this arrangement, because there was unavoidable uncertainty about the tasks that would be required over the course of the contract. Therefore there was a high cost of agreeing to a complete contractual specification of the activities to be performed. Simon did not know that he was modeling exactly the incomplete contract for labor that was the fulcrum of Marx’s economic theory.

Coase or Simon did not directly explain why control rights confer power. As an empirical matter, the firm appears to be a political institution in the sense that some members of the firm routinely give commands with the expectation that they will be obeyed, while others are constrained to follow these commands. If we say that the manager has the right to decide what the worker will do, this means only that the manager has the legitimate authority, not the power to secure compliance. Given that, in a liberal society, the manager is restricted in the kinds of punishment that can be inflicted, and given that the employee is free to leave, it is a puzzle that orders are typically obeyed.

Noticing this, Armen Alchian and Harold Demsetz challenged the Coasean idea that the firm is a mini “command economy”, suggesting that the employment contract is no different in this respect from other contracts:

“The firm … has no power of fiat, no authority, no disciplinary action any different in the slightest degree from ordinary market contracting between any two people … Wherein then is the relationship between a grocer and his employee different from that between a grocer and his customer?” (Alchian and Demsetz 1972)

Oliver Hart (1989) responded:

‘[T]he reason that an employee is likely to be more responsive to what his employer wants than a grocer is that the employer … can deprive the employee of the assets he works with and hire another employee to work with these assets, while the customer can only deprive the grocer of his customer and as long as the customer is small, it is presumably not very difficult for the grocer to find another customer.”

The Exercise of Power

This explanation requires a demonstration that power—in some well-defined sense—can be exercised by employers over employees in the equilibrium of a competitive economy. It is nevertheless puzzling that power is exercised in a competitive economy, in which each actor engages voluntarily in exchanges, from which each is equally free to walk away.

The following sufficient condition for the exercise of power captures the central features of Marx’s (1867) representation of the “despotism” of the workplace:

For B to have power over A, it sufficient that, by imposing or threatening to impose sanctions on A, B is capable of affecting A’s actions in ways that further B’s interests, while A lacks this capacity with respect to B. (Bowles and Gintis 1992)

The definition clarifies the difference between the employer and the grocer in Hart’s response to Alchian and Demsetz. The sanctions imposed on the employee by depriving that employee access to the capital good are severe (technically, first order), while those imposed on the grocer by the departing customer are negligible or zero (second order). The disgruntled consumer who walks out the door does not impose a sanction on the grocer because the grocer (in competitive equilibrium) was maximizing profits by selecting a level of sales that equates marginal cost to the exogenously given price. A small variation in sales has only a second-order effect on profits. But this is not the case for the employer-employee relationship. This is because involuntary unemployment is a characteristic of the competitive equilibrium of a market in which labor effort is not covered in an enforceable contract(Bowles 1985, Gintis and Ishikawa 1987, Shapiro and Stiglitz 1985). The employer’s threat to terminate the worker’s position would thus impose a first-order cost on the worker. This is the basis of the exercise of power by employers.

The incomplete nature of the labor contract is therefore essential to showing both why the employer’s power over the worker is essential to profit-making, and also how it can be sustained by equilibrium unemployment. Marx understood the first but not the second, providing instead a dynamic (and not entirely convincing) account of how the reserve army would be sustained in the long run.

Microeconomist or Precursor to Modern Micro?

Marx was a pioneer in the study of principal-agent relationships, though of course he did not use the term. Principal-agent models now form the microeconomic foundation for the study of relationships among classes (though economists do not use that term) in capitalist and other economies, for example the standard treatments of the exchanges between employer and employee, or between lender and borrower. These models are essential to current analysis of workaday economic problems such as the cyclical patterns in wage-setting and productivity, and the quantity constraints that borrowers face in credit markets. Both of these problems have substantial microeconomic importance, but are also important foundations of macroeconomics.

Marx was a visionary precursor of modern microeconomics, and modern microeconomics has repaid him the favor by clarifying the limits of some of his most important ideas. Among them the labor theory of value as a representation of a general system of exchange (Morishima 1973, 1974), and his “theory of the tendency of the profit rate to fall” (Bowles 1981, Okishio 1961). As Michio Morishima (1974) pointed out, Marx did not resolve the outstanding theoretical problems of his day, but rather anticipated problems that would later be addressed mathematically.

Modern public economics, mechanism design and public choice theory has also challenged the notion—common among many latter-day Marxists, though not originating with Marx himself—that economic governance without private property and markets could be a viable system of economic governance.

Political and Economic Problems

In 1972, Abba Lerner astutely identified one of the limits of the neoclassical paradigm. A contract transforms “a political problem into an economic problem. An economic transaction is a solved political problem … Economics has gained the title Queen of the Social Sciences by choosing solved political problems as its domain.” (Lerner 1972)

Whether this is a feature or a bug depends on your point of view. The Queen’s domain has not seemed too cramped because the same paradigm provided a reason to think that unsolved “political problems”, such as the incomplete nature of the labor contract, or the exercise of power by employers over workers, were illusions. Joseph Schumpeter made this point: “What distinguishes directing and directed labor appears at first sight to be very fundamental,” he wrote. But, he argued, in reality the difference “constitutes no essential economic distinction … the conduct of the former is subject to the same rules as that of the latter … and to establish this regularity … is a fundamental task of economic theory.” (Schumpeter 1934)

Why, one wonders, would Schumpeter consider this point to be of such exceptional importance? The answer is that if Marx’s despotism of the workplace is real, then the liberal argument against economic democracy—there’s nothing there to democratize—is false.

Editors’ note:Samuel Bowles is a Research Professor and Director of the Behavioral Sciences Program, Santa Fe Institute. This column is based on a larger work of the same title to be published in Japanese in a special issue of Keizai Seminar, edited by Naoki Yoshihara.

References

Alchian, A A and H Demsetz (1972), “Production, Information Costs, and Economic Organization”, American Economic Review 62(5): 777-95.

Bowles, S (1981), “Technical Change and the Profit Rate: A Simple Proof of the Okishio Theorem”, Cambridge Journal of Economics 5(2): 183–186.

Bowles, S (1985), “The Production Process in a Competitive Economy: Walrasian, Neo- Hobbesian, and Marxian Models”, American Economic Review 75(1): 16-36.

Bowles, S and H Gintis (1992), “Power and Wealth in a Competitive Capitalist Economy”, Philosophy and Public Affairs 21(4): 324-53.

Coase, R H (1937), “The Nature of the Firm”, Economica 4: 386-405.

Gintis, H and T Ishikawa (1987), “Wages, Work Discipline, and Unemployment”, Journal of Japanese and International Economies 1: 195-228.

Hart, O (1989), “An Economist’s Perspective on the Theory of the Firm”, Columbia Law Review89(7): 1757-74.

Keynes, J M (1925), “Soviet Russia.” Nation and Athenaeum, 17, 19 and 24 October.

Lerner, A (1972), “The Economics and Politics of Consumer Sovereignty”, American Economic Review 62(2): 258-66.

Mark, K (1867), Capital, Critique of Political Economy, Verlag von Otto Meisner.

Marx, K (1939), Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy, Marx-Engels Institute.

Morishima, M (1973), Marx’s Economics: A Dual Theory of Value and Growth, Cambridge University Press.

Morishima, M (1974), “Marx in Light of Modern Economic Theory”, Econometrica 4: 611-32.

Okishio, N (1961), “Technical Changes and the Rate of Profit”, Kobe University Economic Review 7: 85-99.

Samuelson, P (1962), “Economists and the History of Ideas”, American Economic Review 51(1): 1-18.

Schumpeter, J (1934), The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest and the Business Cycle, Oxford University Press.

Shapiro, C and J Stiglitz (1985), “Equilibrium Unemployment as a Worker Disciplining Device: A Reply”, American Economic Review 75(4): 892-93.

Simon, H (1951), “A Formal Theory of the Employment Relation”, Econometrica 19(3): 293-305.

Vrousalis, N (2013), “Exploitation, Vulnerability, and Social Domination”, Philosophy and Public Affairs 41: 131-57.

Yoshihara, N (2017), “A Progress Report on Marxian Economic Theory and on Controversies in Exploitation Theory since Okishio, 1963”, Journal of Economic Surveys, forthcoming.

Disclaimer: The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.