In an interview with ProMarket, Facebook early investor Roger McNamee talks about his efforts to get Facebook to fix its business model and the moment he realized the social media giant is unwilling to change.

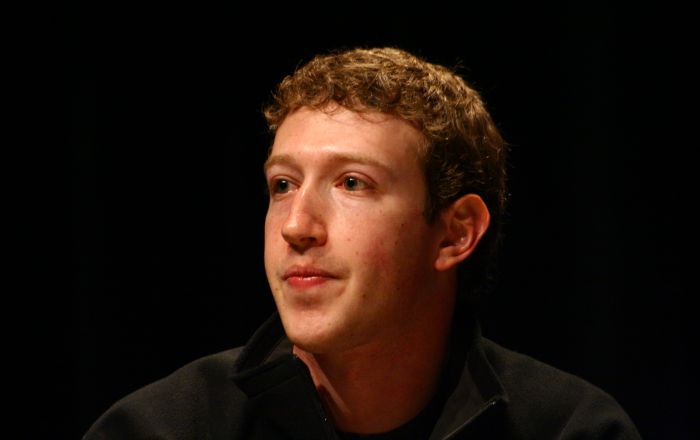

With Facebook increasingly mired in controversy following the Cambridge Analytica data harvesting scandal, an apologetic Mark Zuckerberg broke five days of radio silence on Wednesday as he made the media rounds. Facing a transcontinental backlash and intensifying calls to regulate Facebook, Zuckerberg expressed regret and even some openness to government regulation, so long as it’s the “right” regulation. Echoing these sentiments, Facebook’s COO Sheryl Sandberg also said that Facebook is “open to regulation.”

Belated public statements aside, many are skeptical of Facebook’s willingness to address its privacy issues, not least because the company reportedly knew for two years that Cambridge Analytica had harvested the personal data of millions of users without their consent. The FTC is currently investigating whether the company violated the terms of a consent decree it signed with the agency in 2011 to settle charges that it deceived consumers by sharing data they were told would be kept private with advertisers and third-party apps. As part of its agreement with the FTC, Facebook agreed to conduct regular privacy audits, conducted by independent auditors, for a period of 20 years. If the FTC finds Facebook to be in violation of the agreement (it already suspected Facebook of violating it before, in 2013), the company could be fined billions of dollars. In a letter to Facebook, senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) already requested that the company list all the incidents from the last ten years in which third parties violated its privacy rules and collected user data, in addition to providing copies of every privacy audit it prepared since 2011.

Moreover, the Cambridge Analytica revelations helped shed light on a greater problem: Facebook’s business model, which, as Zeynep Tufekci wrote in the New York Times , relies on massive surveillance of users “to fuel a sophisticated and opaque system for narrowly targeting advertisements and other wares to Facebook’s users.” Former employees and third-party app developers have attested that Cambridge Analytica was not alone: other firms have been utilizing the same covert data harvesting methods as well.

Roger McNamee probably has more reasons than most to doubt Facebook’s act of contrition. As an early investor in the company and former mentor to Mark Zuckerberg, McNamee—a renowned venture capitalist and cofounder of the private equity firm Elevation Partners—played a pivotal role during the company’s early days, advising Zuckerberg to refuse a billion-dollar acquisition offer from Yahoo in 2006 and helping facilitate the hiring of Sandberg. But starting in 2016, when he first noticed bad actors were exploiting Facebook’s algorithms and advertising tools and alerted Zuckerberg and Sandberg, McNamee had been trying unsuccessfully to get Facebook to acknowledge that its product was putting people in harm’s way.

This process, said McNamee in a recent interview with ProMarket, gradually turned him from a “huge fan” into one of Facebook’s harshest critics. “I arrived at this by really small degrees over almost two years,” he says. “With extreme reluctance, I realized that these people whom I trusted and helped were committed to a course of action that I could no longer support and that my friendship with them had to be put in a box while we address the threat to democracy.”((Facebook did not respond to a request for comment.))

“Facebook Wasn’t Hacked”

By the time he first met Mark Zuckerberg, in 2006, McNamee was already a prominent tech investor, best known for running the T. Rowe Price Science & Technology Fund and cofounding Silver Lake Partners and later Elevation Partners. Introduced to the then 22-year-old Zuckerberg through a senior Facebook executive, McNamee had advised Zuckerberg on how to avoid selling the company, launching a years-long mentorship that also saw him become an early investor. “He had plenty of other important people in his life, but I was able to do a few things that really mattered,” says McNamee. By the time of Facebook’s IPO, he wrote in a recent piece in the Washington Monthly, the mentorship had ended and fellow board members Marc Andreessen and Peter Thiel took on the role of mentoring Zuckerberg. McNamee remained an investor, a friend, and, most importantly, “a huge fan of Facebook.”

“I loved the product and was immensely proud of having contributed to its success, in ways that matter even to this day,” he says.

In February 2016, however, McNamee started to notice a number of disturbing trends: a deluge of troubling messages was coming out of Facebook groups ostensibly associated with the Bernie Sanders campaign. “These were these deeply misogynistic, really inappropriate things. And they were spreading virally, which would suggest that somebody had a budget behind them, and that was really shocking to me. I didn’t know what to make of it. Then, a month later Facebook had to expel a group that was using its API to scrape data about people who expressed interest in Black Lives Matter and sold that data to police departments, which was a clear violation.”

The third shock was the Brexit vote in June 2016. “I realized, oh my gosh, you get this incredibly surprising outcome where one of the factors was that Facebook had conferred an extraordinary advantage to one side, the Leave campaign. Facebook’s algorithms appeared to give much greater power to those inflammatory messages,” says McNamee.

The fourth sign that something had gone wrong was when the Department of Housing and Urban Development launched an investigation following concerns that Facebook’s advertising tools allow real estate advertisers to discriminate users according to race. “At that point I’ve got four data points in essentially four different areas, all pointing to the same problem, which is that Facebook’s algorithms and business model essentially enable bad actors to harm innocent people,” says McNamee.

Deeply disturbed, McNamee wrote an op-ed, but instead of publishing it he sent it to Zuckerberg and Sandberg. “I sent it to Mark and Sheryl because they were my friends. It was my biggest personal investment, and I was still totally loyal to the company.” Zuckerberg and Sandberg responded politely, but firmly: “They didn’t agree with my interpretation. They thought these were isolated events.” They referred him to Dan Rose, a senior Facebook executive with whom he had a great relationship.

For months, says McNamee, he and Rose talked and exchanged emails. When the presidential election ended with an unlikely victory for Donald Trump, McNamee again reached out. ”I just went, ’This is crazy. Facebook had influenced the outcome. You’ve got to pay attention to this.’ And Dan is going, ‘No, no, we are a platform, not a media company, so we’re not responsible for what third-parties do.’ I told him, ‘Dan, you’ve got 1.7 billion members—if they decide you’re responsible, it doesn’t matter what the Communications Decency Act says, your brand’s going to get torched, and in the meanwhile you’re torching democracy.’”

McNamee was still trying to get the company to acknowledge the problem internally, with no success, when he met Tristan Harris, a former design ethicist at Google who had been trying to convince people that digital platforms present a public health issue and raise awareness of what he called “brain hacking” techniques.

“When you have a huge artificial intelligence, the way that Facebook and Google have, and you marry that to a software product that captures every human action—and in the case of Facebook captures emotional states, across the day and all their interactions—you have massive power. You put that on a smartphone, which is available every waking moment, and the combination of those things creates filter bubbles, which is to say the ability for each person to live in their own context, their own world, with their own facts, and to surround themselves with like-minded people so that non-confirming facts don’t get through. When people are in that heightened state, and when the advertisers have the ability to take advantage of the outrage curve—which is to say pushing the buttons of fear and anger, the things that create maximum engagement—people are really vulnerable and you can implant ideas in their head that they will think are their own,” McNamee explains.

Along with Harris, McNamee figured out real issue: it wasn’t the algorithms—it was the business model. “When I heard Tristan, I suddenly understood the entire context of what I’d seen in 2016,” he says. “The issue wasn’t social networking, the issue was the advertising and the incentives created by the advertising model.”

In the months that followed, McNamee and Harris spoke to legislators like Senators Mark Warner (D-Va.) and Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), trying to get them to see the wider context of the Russian interference in the 2016 election. “As we dug into it, people started to come to us and tell us more stuff, and as we came to understand it, we came to appreciate that Facebook wasn’t hacked. That, in fact, the Russians used tools that were created for advertisers and they used them exactly the way they were meant to be [used]. It’s just that there was nobody was guarding the henhouse.”

The second thing they learned, adds McNamee, “was that there were people inside Facebook who know they were dealing with the Russians and did it anyway.”

|

“When I heard Tristan, I suddenly understood the entire context of what I’d seen in 2016,” he says. “The issue wasn’t social networking, the issue was the advertising and the incentives created by the advertising model.” |

Facebook, however, still refused to acknowledge the problem, even after a Columbia University researcher by the name of Jonathan Albright published a study showing that Russian propaganda may have been shared hundreds of millions, possibly billions, of times on Facebook. “At this point you’re going, ‘Excuse me guys, time to fess up.’ Now we know it not just happened, but that it had a huge impact. But Facebook still denied.” In August 2017, nine months after he reached out to Facebook for the first time, McNamee went public with his concerns via an op-ed in USA Today. “I’ve given Facebook nine months to think about it, and all they’ve done is deny to that point,” he says. “And this scares me, right? The algorithms and the business model create the wrong incentive, and they’re in denial. This is really bad, we’ve got another election coming less than a year away, and they’re not doing anything about it. And they’re the only people in a position to fix the problem.”

Only in October 2017, on the eve of a series of Congressional hearings, did Facebook finally admit that 126 million Americans may have been exposed to Russian propaganda around Election Day. “I don’t know when they figured it out, but I can guarantee it wasn’t the night before the hearing,” McNamee opines.

Facebook, however, was still dismissive of the wider implications. “At that point I’m going, ‘This is really weird.’ I mean, these guys are actively denying the obvious. It’s just really hard to understand the whole thing,” says McNamee.

Nevertheless, he notes, he still gave Facebook the benefit of the doubt, but in December 2017 came the moment he realized that Facebook was unwilling to change. It was when Chamath Palihapitiya, Facebook’s former vice president for user growth, said during an interview at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business that he feels “tremendous guilt” over his part in Facebook’s growth, and that the company “created tools that are ripping apart the social fabric of how society works.” What shocked McNamee, however, was not so much the content of Palihapitiya’s remarks, but what came next. Within days, with his comments going viral, Palihapitiya took back his words.

“Within like 24 hours, not only does he recant with a long Facebook post that was obviously written by the PR department at Facebook, [but] he goes on a PR tour, he goes on Christiane Amanpour’s [show] at CNN, he goes to Davos, telling everybody that Mark’s the only person to solve this problem and that we should all be confident that Mark will do it, because it’s really not that big a deal,” says McNamee. “Chamath is a world-class poker player. This is not a guy easily intimidated. His options vested years ago. Something happened, and I don’t know what it was, but because of the 180-degree flip and the intensity of it, you couldn’t help but imagine that they’d brought really intense pressure to bear.”

Until that moment, McNamee was still hoping Facebook would do what Johnson & Johnson famously did when it found out Tylenol bottles had been tampered with in 1982: take responsibility and fix the problem, turning a PR disaster into a win.

The publication of McNamee’s piece in the Washington Monthly, detailing his concerns about the company’s business model and his unsuccessful attempts to get the company to change, coincided with Zuckerberg’s New Year’s resolution post, where he acknowledged that Facebook had made “too many errors enforcing our policies and preventing misuse of our tools.” McNamee, who viewed Zuckerberg’s post as “disingenuous,” was further dismayed by the subsequent changes in Facebook’s newsfeed—“all of which are things that had they been done in 2015 would have intensified the Russian manipulation and made it more effective.”

“I am sitting there going, ‘Whose side are these guys on?”

“It’s an Authoritarian Model”

Long before the Cambridge Analytica scandal exploded, Facebook and other digital platforms like Google and Amazon were already facing an increasingly fierce backlash over their growing dominance and its implications for democracy, privacy, labor, and the economy as a whole. On April 19 and 20, the Stigler Center will dedicate its annual Antitrust and Competition conference to the impact that concentration among digital platforms is having on competition and the economy as a whole.

McNamee, who along with Harris and other former tech employee co-founded the Center for Humane Technology, an organization seeking to change the culture of the tech industry, is worried about the overall impact that digital monopolies are having on the US and the world. Nevertheless, Facebook remains his primary focus. “I’m concerned about the future of democracy in the United States, and their role in that is simply an order of magnitude greater than anyone else’s,” he explains. “You look at how Facebook’s organized: it’s an authoritarian model. You’ve got a guy at the top with a cult of personality. They have massive global ambitions. They treat their users not as customers, but rather as something you own for the business. They dominate political discourse around the world and they do it in different ways in different geographies.”

The United States is far from the worst example. “You see the UN come out publicly against Facebook for the role it’s playing in the subjugation of the [Rohingya Muslim] minority in Myanmar, which is something that has been characterized by many NGOs as a genocide—and the legitimization of that behavior is taking place over Facebook, being done by allies of the government, presumably with at least the tacit support of Facebook. And you see similar things in the Philippines, and with the suppression of dissent in Cambodia. This has become a very powerful tool of propaganda, and it’s literally everywhere.”

| “The reality is that libertarian values are extremely convenient for tech startups. I mean, ‘Move fast and break things’ is a pretty sociopathic motto.” |

McNamee no longer invests in tech companies. “Philosophically, it wasn’t a good fit,” he says. In Facebook, he notes, one can clearly see the impact that certain philosophies have had on corporate culture. “The two most influential people on [Facebook’s] board of directors over the last seven to eight years have been Peter Thiel and Marc Andreessen, both of whom are brilliant men whose economic and political philosophy is deeply libertarian. So in a world where we already prioritize the individual over the collective and we take the Ayn Randian view that none of us are responsible for the downstream consequences of what we do, Mark was surrounded by people who were particularly deep believers in that philosophy, with no contrary voices.”

He adds: “The reality is that libertarian values are extremely convenient for tech startups. I mean, ‘Move fast and break things’ is a pretty sociopathic motto. The role that the investors played philosophically, in my mind, was important at the margin, but these companies grew up in an environment where everybody believed that to one degree or another.” The result, he says, is that many tech firms are now predatory. “In the case of Facebook, I think you can make legitimate case that it has become parasitic, because a lot of the users are being harmed by using the product.”

The tech world today, says McNamee, is completely different from the one he came into in the early 1980s, a “world of scarcity, where there was never enough processing power, memory, storage, or bandwidth to do the thing you wanted to do.” Enjoying a “surplus of everything” and lacking a “sense of history,” tech companies have since opted to get as big as they could possibly get. “Everything was about getting rid of friction. If you think about what was wrong with companies like Uber or what went wrong with Facebook, it’s that they did not recognize the legitimacy of friction or any obstacles. They didn’t recognize that regulations serve a public good. Their goal was just blow up and buy everything. That philosophy was so deeply ingrained in Silicon Valley that when you talk to people today, most of them still do not recognize why what’s happening with Facebook is a problem.”

Disclaimer: The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.