Many of Stigler’s views on monopoly and antitrust were consistent through the decades. Even after his concerns of monopoly began to recede, he continued to believe that monopolies and oligopolies were still prevalent in the American economy and that they “should be a source of serious concern for public policy.”

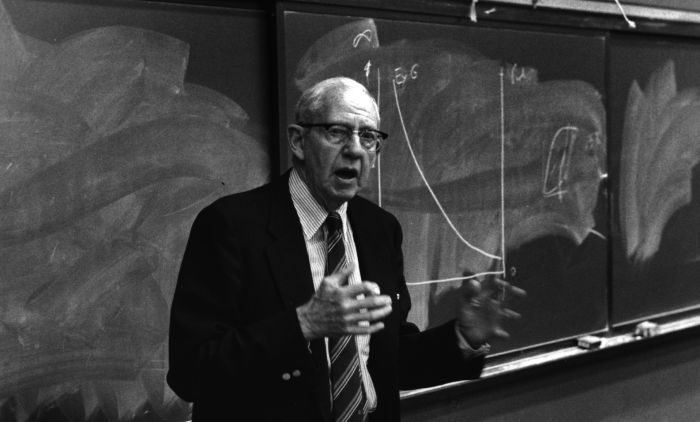

October 20 marked the 35th anniversary of George Stigler’s Nobel prize, the first of Booth School of Business’s grand total of eight Nobels. Ahead of his talk at our November “Stigler in the 21st Century” conference, Dartmouth professor Douglas Irwin offers thoughts on Stigler’s legacy.

George Stigler devoted much of his professional career to examining market competition and the price system. In particular, he had a deep interest in trying to understand how public policy might promote competition and deal with the problem of monopoly. This led him to grapple with antitrust laws, a subject on which his views changed subtly over time.

George Stigler devoted much of his professional career to examining market competition and the price system. In particular, he had a deep interest in trying to understand how public policy might promote competition and deal with the problem of monopoly. This led him to grapple with antitrust laws, a subject on which his views changed subtly over time.

Stigler’s early views were shaped by Henry Simons, his teacher at the University of Chicago in the 1930s, when he was a graduate student. In his 1934 tract A Positive Program for Laissez Faire, Simons passionately argued that government should promote competition through an aggressive antitrust policy. “There must be outright dismantling of our gigantic corporations, and persistent prosecution of producers who organize, by whatever methods, for price maintenance or output limitation,” Simons insisted. “In short, restraint of trade must be treated as a major crime.” “No doubt my memory exaggerates the influence of this voice,” Stigler later wrote, “which sounded so clear and brave when I listened to it in a Chicago classroom.”

Stigler echoed these sentiments in a 1952 article in Fortune magazine entitled “The Case against Big Business.” He argued that “the fundamental objection to bigness stems from the fact that big companies have monopolistic power.” Big business was not necessarily more efficient than medium-sized business, he stated, and weakened political support for a private enterprise economy by giving rise to demands for government regulation and the oversight of business activities. He therefore supported the antitrust laws to prevent conspiracies in restraint of trade and block the mergers that were likely to diminish competition. But Stigler also agreed with Simons that the dissolution (breaking up) of large corporations should also be considered.

| “There must be outright dismantling of our gigantic corporations, and persistent prosecution of producers who organize, by whatever methods, for price maintenance or output limitation,” Simons insisted |

Over the next decade, however, Stigler’s concerns of monopoly began to recede and he no longer favored the dissolution remedy. What changed, and—just as importantly—what did not change in Stigler’s views about monopoly and the role of antitrust policy?

In his memoirs, Stigler attributes his downgrading of the importance of monopoly to three factors: (i) the fact that business concentration did not necessarily imply a lack of competition or the prevalence of anticompetitive practices, as previously thought; (ii) the persuasion of Aaron Director, his friend and colleague, who skillfully interpreted many business practices as profit-maximizing rather than monopolistic exploitation; and (iii) his own work that showed the difficulty of sustaining oligopolistic collusion. He came to believe that “competition is a tough weed, not a delicate flower.” For this reason, he no longer viewed big business as a major problem in itself, and dissolution “should be used only in the most extreme occasions.”

And yet Stigler continued to believe that monopolies and oligopolies were still prevalent in the American economy and that they “should be a source of serious concern for public policy.” He continued to support the antitrust laws, particularly the Sherman Act, and encouraged the government to block anticompetitive mergers. In fact, Stigler undertook pioneering studies on the “positive economics” of the antitrust laws, i.e., trying to determine their actual economic impact. He concluded that “the Sherman Act substantially reduced the amount of effective collusion and had at least a modestly deterrent effect upon concentration. . . . There is no other method of regulating business which has been so efficient and so free of gross waste as our antitrust policy.”

Furthermore, and perhaps ironically for someone who proposed the industry capture theory of government regulation, Stigler studied the origin of the antitrust laws and concluded that they were a “public-interest law in the same sense in which I think having private property, enforcement of contracts, and suppression of crime are public-interest phenomena.” As he put it in a 1982 interview, “I like the Sherman Act. I don’t like the Clayton Act” (which dealt with practices such as price discrimination, exclusive dealings, and interlocking boards).

Thus, many of Stigler’s views on monopoly and antitrust were consistent through the decades. He always questioned evidence that competition was on the decline and consistently observed that government policies themselves were an important impediment to competition. In 1942, he noted, as he would in later decades, that “the major factor in the decline of competition has been governmental support of monopoly.” This is one reason why his research eventually led him to study the causes and consequences of government regulation of business.

View the full program and register to attend the “Stigler in the 21st Century” conference hosted by the Stigler Center for the Study of the Economy and the State at Chicago Booth on November 8–9, 2017.

Disclaimer: The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.