“Despite some specifics on the national level, I would say that all the populist regimes and leaders share common characteristics,” says José Ugaz, the chair of Transparency International and a leading anti-corruption crusader who helped bring down the Fujimori regime in Peru.

In the final days of his regime, Alberto Fujimori, the strongman who ruled Peru from 1990 until 2000, made a fatal mistake. A tape had been released showing his then-powerful spy chief Vladimiro Montesinos bribing a congressman from the opposition party, and huge public protests erupted, leading Montesinos to flee the country for fear of prosecution.

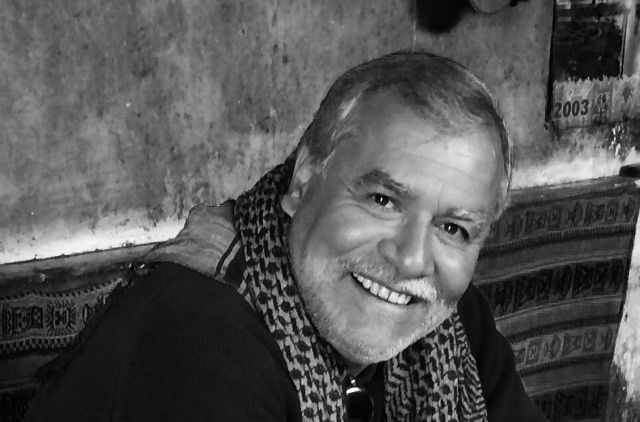

Feeling isolated, Fujimori decided to try to appease public pressure by putting an anti-corruption attorney named José Ugaz, who had already investigated two major corruption cases, in charge of the state investigation of Montesinos, thinking he would be malleable.

Ugaz, however, turned out to be an aggressive investigator, launching over 200 criminal investigations against more than 1,500 people, freezing more than $200 million in foreign assets, and recovering tens of millions in cash. He sent dozens of high-level public officials to prison, among them Fujimori’s attorney general, Peru’s chief justice, the president of congress, and dozens of ministers, mayors, governors, and judges—members of the “criminal network,” as he describes it, that allowed Fujimori to seize power and turn Peru into an authoritarian regime.

When Ugaz began investigating the president himself for money laundering, Fujimori fled the country, resigning by fax and requesting asylum in Japan. Thus ended Fujimori’s decade-long regime. He has since been imprisoned for the crimes he committed during his term, convicted of human rights violations and abuses of power, and sentenced to more than 25 years in prison. Nevertheless, he continues to be a popular political figure in Peru.

Ugaz, a former professor of criminal law at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, is still a leading anti-corruption crusader and the current chair of the board of Transparency International. We recently sat down for an interview with Ugaz about the lessons of the Fujimori case for dealing with populist plutocrats, and why he sees similarities between Fujimori’s Peru and the United States and some European countries today.

When asked why Fujimori decided to put him in charge of the investigation, a decision which ultimately brought an end to his rule, Ugaz says: “There was a mix of reasons why he did it. I think he was not thinking clearly. He was in a very emotional situation. I had two previous appointments by his government to take over some cases of corruption. I was suggested by the minister of justice, who was my former professor and friend. At the time, I assume that he thought he could control me and the new attorney general. He tried, but that didn’t work.”

Q: Obviously, Fujimori is unique to Peru’s particular circumstances and political culture. However, do you see any similarities between him and other populist leaders?

Yes. Despite some specifics on the national level, I would say that all the populist regimes and leaders share common characteristics. We find many common threads [linking] Berlusconi and the experiences of Thailand and the Philippines with populist presidents.

First, these type of leaders build an image based on lies. They also have a way of connecting with people, at least at the beginning. That’s the real reason behind their success. These type of leaders can connect with the needs of the people—even though they are lying, people believe that things are going to change.

A third similarity has to do with the outsider model we’ve seen in many other countries in recent years: leaders confronting the traditional political class that has failed for years, even decades.

They appear to be out of the political class, but in the end make the situation worse.

We see, for example, what’s going on in Guatemala, where a total outsider, a comic [Jimmy Morales] appears as president of the country. The basis of his plan was fighting corruption, and now he’s the first one in the country trying to bring impunity to all the corrupt practices that took place in the recent past.

Q: Fujimori ended up fleeing Peru and was ultimately arrested, convicted and imprisoned for his crimes. By all accounts, the opposition to his regime was successful. Yet his political influence is still significant. His daughter almost became president. Is it possible to completely eradicate the threat of this kind of leaders rising to power, or is it a danger that is always lurking?

It is possible to eradicate it, but it takes time, because it implies cultural change.

It’s not only Fujimori, look what’s happening in Brazil: [Former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva] has been proven to be involved in corrupt practices on behalf of big construction companies. He’s been convicted already and sentenced to 9 years in prison, pending his appeal. But in the polls this week, he appears to have a good chance of being re-elected president. People say, “He’s corrupt, but he’s mine,” or, “He’s like me,” or, “This time he will change.” There are different reactions, but this is commonplace.

In Fujimori’s case, he’s in prison, but many people still remember the good things: He allegedly defeated terrorism, he controlled inflation, he brought order, he built roads. People remember that. They say, “Yes, he was corrupt, but all presidents have been corrupt.” So it’s something they’re willing to put up with.

Q: The appeal of populist plutocrats seems to be remarkably resilient, despite their failures, crimes, and abuses of power. Is it mere nostalgia, or is it because of the things they did while in power?

It’s a mix of both. In Chile, for example, it’s been absolutely proven that Pinochet was responsible for killing thousands. Yet when he left, people started saying, “We need him back.” Other countries with authoritarian traditions, like mine, were saying, “Why don’t we have a Pinochet here?”

Populist plutocrats have charisma and they connect to people, bringing some sort of solution to their needs—sometimes only rhetorically, and sometimes they achieve some of the things they promise during their campaigns.

Q: It makes sense to find parallels between countries like Chile, Peru, and the Philippines, countries with authoritarian traditions where populist plutocrats rose to power. But do you see similarities between the experience of those countries and the present-day challenges of developed democracies, like the U.S.?

What’s happening in the United States and also in other European countries is a reaction against the political class. People are looking for new leadership. They are tired of the traditional leaders they had, their governments have not provided security or economic development, some of them have recently experienced [financial] crises. People are looking for new faces and new platforms, and they are willing to believe in something different. This is a great opportunity for these outsiders to appear: improvising as they are without political parties, without structure, without plans, without teams to work with.

I think that’s the main basis for similarities between both types of experiences.

Q: What is the role of corruption in the rise of this type of political leaders?

Corruption is in the middle of this. However, there is a contradiction there: If you ask people why they are voting for such a candidate, they say, “Yes, he’s corrupt, but he will do something for me.”

That’s one part of the phenomenon. The other part—and I’ve seen this several times in Latin America—is that because corruption is a crime that is singular, in that many of its victims are not conscious of the fact that they are victims, often it has no social reaction. I once saw a very poor woman interviewed in the street by a journalist. “‘Why are you voting for this candidate? He’s corrupt,’ he asked her. She said: ‘I really don’t care. I have no money, so that can’t hurt me.’” She didn’t realize she was a victim of people like the candidate she was voting for.

Often voters will vote for the corrupt candidate because they feel that they are out of the system. Like in gambling, they’re thinking, “Maybe they’ll provide me with something.”

Q: How was Peru able to overcome this? How were you able to withstand Fujimori’s and Montesinos’s pressures? What made Peru able to resist Fujimori’s state violence and corruption and overthrow him?

I think the difference between the Peruvian case and others is that in the case of Peru, the entire state collapsed. When the first video appeared where Montesinos was bribing an elected congressman from the opposition, that was too much. People were really striving for change, the opposition were also agitating masses, and this is what triggered thousands and thousands of people to go out to the streets to express their outrage.

Montesinos left immediately because he was afraid of what could happen, and then Fujimori was trapped. He was confused, and that’s when he made the decision of putting me in charge of the investigation on behalf of the state. He didn’t calculate that by then, all the strings he used to pull were out of his control.

I am optimistic about the possibilities of Peru overcoming its current situation of corruption. Like in many other countries in the region, Peru’s attorney teneral’s office is reacting strongly against the corrupt. We have a vibrant and active investigative journalism monitoring corrupt practices and, most importantly, the people are starting to react against corruption. In the most recent survey on perceptions of corruption in Peru, 75 percent are demanding the president take action against corruption. We have to assure real change and sustainability.

Disclaimer: The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.