How much does investigative journalism cost? What are its benefits? Why is it so hard to monetize? Can markets keep on providing this service? In an interview with ProMarket, James Hamilton offers answers to these and other questions related to investigative journalism.

In 2015, the Washington Post ran an investigative series on police shootings. In it, it was revealed that the Washington police supplied some of its policemen with a gun that had an extremely light trigger, which was possibly a main reason for the rise in fatal police shootings. As a result of the Post‘s reporting, the police chief made policy changes, including an investment of $4 million in training, and the rate of fatal shootings in DC went from about 12 a year to about 4 a year.

Stanford professor James (Jay) Hamilton did the math: “You have eight lives saved. The Office of Management and Budget values a life at $9 million. Eight people times $9 million is $72 million.”

Even without trying to attach a dollar sum to human lives, it is quite evident that the Post’s series was extremely beneficial to society. It also earned the newspaper a Pulitzer Prize, but running the series was probably not immediately economically beneficial: Hamilton estimates the cost of the series at about $400,000—far more than the newspaper may have gained in additional subscription revenues, and certainly a fraction of the economic gain to society.

Hamilton’s book Democracy’s Detectives: The Economics of Investigative Journalism (Harvard University Press, 2016), published last October, makes clear that this is not an isolated example: Investigative journalism is expensive and notoriously hard to monetize. At a time when newspapers’ revenues are getting smaller and smaller, it is becoming even harder to produce.

It’s not that investigative journalism has no economic and societal value. On the contrary: Word-for-word, it arguably carries the highest value of all journalistic products. It also fills a huge market failure, as it represents those who have no incentive to group together and fight for free markets and against corruption and abuse of power. “While everybody benefits from a competitive market system,” wrote Luigi Zingales, Director of the Stigler Center and one of this blog’s editors, “nobody benefits enough to spend resources to lobby for it. Business has very powerful lobbies; competitive markets do not. The diffused constituency that is in favor of competitive markets has few incentives to mobilize in its defense.”

Hamilton is the Hearst Professor of Communication at Stanford University and the director of its journalism program. He has a BA in Economics from Harvard University, where he did his PhD as well. He started his career as an environmental economist and later shifted to journalism. In 2004, he published his first book on the economics of journalism, All the News That’s Fit to Sell: How the Market Transforms Information into News (Princeton University Press, 2004), where he offered much-cited explanations on how business considerations drive news.

Hamilton’s new book is focused squarely on investigative journalism, perhaps the product that’s most synonymous with journalism, as well as a major loss-leader. How much does investigative journalism cost? What are its benefits? Why is it so hard to monetize? Can markets keep on providing this service? In Democracy’s Detectives, Hamilton tries to answer these and other questions.

We recently sat down with Hamilton for an interview, which we will publish in three installments. In the first part, we will talk about Hamilton’s career, the uniqueness of investigative journalism, who are its main producers, why it is underprovided in the marketplace, and why ESPN has more viewers than C-SPAN.

Guy Rolnik: You were trained at Harvard as an industrial organization economist. Correct me if I’m wrong, but most IO economists tend to be not very interested in media—specifically not in investigative media. Something happened during your career that got you interested in that, and made you believe we should think differently about media markets. Can you elaborate on that?

Jay Hamilton: Sure. I’ve always been interested in how information provision affects people’s decisions. In particular, the first 10 years of my career I was an environmental economist. I was looking at how the provision of information by the government about pollution—what each company was putting out in its smoke stacks, putting into streams—affected behavior.

The U.S. had a very successful program—the Toxic Release Inventory Program —which actually brought new information to the market. I know that because I did a stock market event study and showed that the first time the government’s pollution data was released, there was a reaction in the market and firms responded to that by reducing their emissions.

Along the way, I read that the government was thinking about developing report cards on who was supporting violent television programming. That idea of shaming companies who were advertising on violent programs, much like they were trying to affect the decisions of polluters, made me realize that you could take the framework of environmental economics—basically, people generating negative spillovers on society—and transpose that to the media.

I actually wrote a book called Channeling Violence, which looked at TV violence as a pollution problem. The essential insight is that we probably have too much television violence because companies, especially in the world of the First Amendment, aren’t led to internalize some of the negative impacts of their images that they create.

Then, I got interested in an area where the media produces too little of something, and that’s public affairs reporting. I wrote a book called All the News That’s Fit to Sell that basically says we think of journalism as the five Ws—who, what, when, where, and why—but they’re actually a set of five economic Ws that determine media content. Who cares about a particular piece of information? What are they willing to pay for or what are others willing to pay for their attention? Where else can you reach these people? When is it profitable? That brings in the cost structure of stories. Why is it profitable? That brings in the property rights to information.

Journalists don’t roll out of bed in the morning generally and say, “It’s a great day to maximize profits,” but the sets of stories and media organizations that survive are really determined by those five economic Ws. So, I tend to view the news not as a mirror of reality but as a product that’s determined by supply and demand factors.

You mentioned investigative reporting. Investigative reporting is underprovided in the marketplace. We do see some investigative reporting, obviously. It’s often done by larger organizations where they can spread the cost across many readers, or it’s done by nonprofits. It’s done sometimes when there’s individual or family ownership, when people are willing to trade off some profits for the idea that they’re doing the right thing. It’s sometimes done as a product differentiation strategy, especially in the world of the internet, where you need to tell a story that’s distinctive, that doesn’t have good substitutes.

Investigative reporting can develop a long-term brand for that. It’s also a great morale booster for newsroom employees.

In general, investigative reporting is underprovided for a couple of reasons. Number one, relative to the other stories that you could tell, it’s extremely expensive. Investigative reporters and editors define what they do as original stories of substantive interest to the people in the community that somebody is trying to keep a secret. The three economic concepts there are original stories, which means there’s a fixed cost to creating the story; impact, which means substantive interest to the community, and spillovers on many people. When a story gets told, it can change legislation and public policy, which is true for people who may never be readers of the outlet, but those spillovers are very hard to monetize. If somebody wants to keep a secret, that’s transaction costs or hustle costs.

The government will try to make it hard for you to understand what actually is going on. Investigative reporting is underprovided because it’s more expensive. Think about entertainment stories or sports stories, where there are people involved that actually have an incentive to talk to you. They want you to go to their movie. They want you to go to their sporting event. You don’t see that with some politicians. In Democracy’s Detectives, I do case studies where I show that for each dollar spent by a newspaper on an investigation, it can generate hundreds of dollars in net benefits to society when policies change.

Again, those benefits are spread across many people, and it’s very difficult for the media organization to recoup its investment.

GR: When we look at the benefits, it’s very easy to see that they are not exploitable. When I look at investigative journalism, it’s sort of obvious to me—specifically investigative journalism that looks at the failure or capture of regulators, and crony capitalism. Is investigative journalism a public good? Do economists and people in policy view journalism as something that we should leave to the market?

JH: There are two things to consider here. One is the set of people who believe that the public interest is defined by the public’s interest. They believe the TV is just a toaster with pictures and that there’s nothing special about information markets. In a way, you can understand what they’re talking about, because we’re in a world of a surplus of information.

What you may miss is the following. In his book Economic Theory of Democracy, Anthony Downs said that we each have four information demands: our life as consumers (what product am I going to buy?), our life as workers or producers (how can I do my day job better?), our life as audience members (who do I find personally entertaining?), and our life as citizens or voters.

In some ways, we are in a golden age in those first three demands. For the voter information demand, that’s where the market truly breaks down. Even if I care about a particular issue of public policy, my vote doesn’t matter in a statistical sense, so I don’t seek out the information.

If I did that in the entertainment market, I would miss a movie. If I did it in my work life, I might produce a book that was wrong and I would pay the price in terms of my reputation. If I’m misinformed about politics, there’s really not a big feedback loop for me individually.

What that means is that there’s a difference between what people need to know as citizens and what they want to know as audience members. That sets up a gap in expressed demand. Now, we do see public affairs coverage. I call it the “Three D’s”: duty, diversion, and drama. Some people feel they have a duty to become informed about politics. There, you’re seeking out the information more as identity consumption. You think that you should participate, you should know. Diversion: there’s a set of people who find C-SPAN as interesting as ESPN. That’s about one percent of the U.S. population, the set of people who would watch The PBS NewsHour. Then there’s drama. Maybe I can’t tell you about the details of climate change, but I can tell you about an email scandal. I can tell you who’s ahead or who’s behind. I could talk about politics as a horse race. We do see coverage, but it’s often aimed at one of those other three demands rather than the voter demand.

You mentioned economists. They are often living in a world of producer demand information. If you think about the top one percent in the U.S., they have a different information set than the rest of us. The example of this might be Federal Reserve policy. Some of us might read the Wall Street Journal, but there is another set of folks who pay $100,000 a year to subscribe to a newsletter from a former Federal Reserve official.

If you’re involved in policy-making, especially if you’re in an interest group, you know more, but that’s because you have a producer demand. Getting the information actually makes your day job easier and more lucrative. That’s the type of information that’s not getting to the rest the public.

GR: You’re actually saying that the people at the top of the income ladder have a lot of information networks and a lot of access to information. It’s almost as if they feel that they don’t really need the service of the investigative journalist.

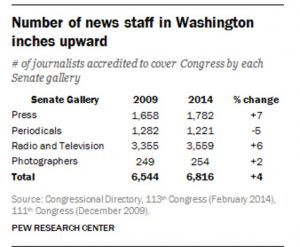

JH: If you actually look at the Pew Research Center’s data on journalists in Washington, it hasn’t gone down, it’s just changed in the composition. You used to have newspaper groups who had Washington bureaus, those people have gone away now.

If you look at local newspapers, they dropped by 40 percent in terms of their employment. I find in my book that FOIA requests from local newspapers dropped by 50 percent at the set of federal agencies that I looked at, but there’s a thriving newsletter business.

There’s a thriving niche business aimed at the people whose business is governing and influencing politics. I actually found that FOIA requests by Bloomberg and these niche outlets went up by 40 percent, even while the FOIA requests by local newspapers were going down by 50 percent. There’s a set of people who do understand what’s going on in Washington, but that story isn’t told broadly.