Does the fact that Russian readers consume news produced by government-controlled entities, even though they have access to independent sources, imply a demand for pro-government bias? A new Stigler Center working paper provides a unique view into Russia’s news market.

In May 2014, two months after Russia annexed Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula, Russian president Vladimir Putin awarded over 300 pro-Kremlin journalists with medals for their “objective” coverage of the Ukrainian crisis. One such recipient was Margarita Simonyan, the editor-in-chief of two major government-funded news outlets: English-language television news network RT (formerly Russia Today), which is also active outside Russia, and the international news agency Rossiya Segodnya (which also translates to “Russia today”).

Journalists from two media outlets critical of the Kremlin, the independent television channel Dozhd and the radio station Ekho Moskvy, were not awarded medals.

Putin’s Russia is probably the best “laboratory” in which to conduct research into government-owned vs. independent media. In Soviet Russia, practically all media was government-controlled. Of course, the internet—which allows a much larger variety of citizens, both inside and outside the country, to participate in the news and information discourse—was nothing like its current form. But now, alongside the government-owned media, there are other, more independent sources of information available to Russian citizens, some of which are based outside of Russia and carry many decades’ worth of reputation, such as the BBC and Reuters.

This allows researchers to both pose questions and have enough data to be able to answer them with a reasonable degree of confidence.

Two such scholars are Andrey Simonov, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, and Justin Rao of Microsoft Research, authors of the new Stigler Center working paper “Demand for (Un)Biased News: The Role of Government Control in Online News Markets.” In their paper, Simonov and Rao explore the following questions: Does the fact that Russian readers consume news produced by government-controlled (GC) entities, even though they have access to independent sources, imply a demand for pro-government bias in news? Or is it that perhaps consumers enjoy other aspects of GC news outlets, such as quality and coverage of issues that are noncontentious?

In estimating demand, they found that the average consumer does indeed prefer sources with less pro-government bias, and that frequent consumers have a stronger preference compared with less frequent consumers. This distinction is potentially important because, on the one hand, frequent consumers are a minority of total readers (8.8 percent), but on the other hand their share of actual consumption is 70 percent. Simonov and Rao also found that GC news outlets would have higher market shares in the absence of control. At the same time, they maintain the majority of their readers when control is imposed, suggesting that control is effective.

Simonov and Rao based their study on two datasets. First, they created a list of Russia’s top 48 internet-based news sources (print newspapers, TV, radio and other forms were ignored). Following discussions they had with relevant news professionals, they divided the 48 sources into five groups: (1) independent and not influenced (e.g. the BBC and Reuters); (2) independent but possibly influenced (e.g. newsru.com, which is owned by Vladimir Gusinsky, an oligarch who was in effect banished from Russia by Putin); (3) media owned by people close to the Kremlin (e.g. Izvestia, co-controlled by “Putin’s banker” Yuri Kovalchuk); (4) GC sources (e.g. NTV and TASS); and (5) Ukrainian sources, which are also read by Russians.

The first dataset contained 3.9 million articles (web pages) from all of these sources, published over a two year period between April 1, 2013 and March 31, 2015. The breakdown reveals the significant over-indexed share of pro-Kremlin stories—but also the availability of non-linked sources, even after a 2013 Kremlin crackdown on independent outlets:

That was the information side—the supply side. As for the readership side—the demand side—Simonov and Rao used data from Microsoft (Rao’s employer), collected from the toolbar installed in the company’s web browser, Internet Explorer (IE). This means that the data was collected only from IE users—and only those who had the toolbar installed during the relevant period. The resulting panel constituted 2.17 million users, of which only 284,574 visited a news website over the sampling period. As this data may contain bias, Simonov and Rao compared it to other data sources and found an apparent match in weekly visits over time and a similarity of relative readership among news sources.

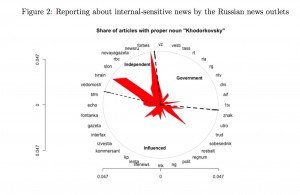

The differences in coverage, they found, are most present in issues where the pro-Kremlin position is distinctly different from (and sometimes opposed to) the position of independent sources. Thus, the authors identified what they termed “sensitive issues” and labeled topics for which they observed censorship as “internally sensitive” news. The Ukrainian crisis, for instance, was one such sensitive issue, and censorship was observed when mentioning a major Putin opponent, Mikhail Khodorkovsky.

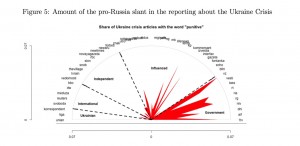

Figure 5 shows how the use of the word “punitive,” which refers to how pro-Kremlin sources described the Ukrainian government’s actions against pro-Russian rebels, underscores media slant in GC outlets:

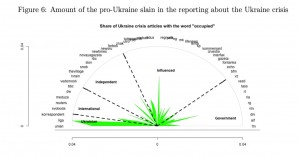

Figure 6 shows Ukrainian media’s slant in relation to the use of the

word “occupied”:

And Figure 2 shows how underreported Khodorkovsky-related stories were among GC sources compared with other sources, especially independent ones:

If there are media outlets that are not slanted and do not self-censor—and assuming that readers are aware of them—why would Russian readers read GC outlets at all? Why would the Russian government invest an estimated $1.2 billion in subsidies to its outlets? And how are GC outlets able to maintain a 35-40 percent market share? In short: What are the factors that drive demand for government-controlled news outlets in Russia?

Simonov and Rao offer two types of approaches to this question: (1) readers see value in reading GC sources, either because they share the same ideology or because they want to know what the government’s positions are; and (2) readers go to GC sources for news items unrelated to the government’s view on contentious issues.

Simonov and Rao define consumer preferences relative to news outlets, topics covered by these outlets on a particular day, and the slant detected in covering sensitive issues.

They give special consideration to changes in the relative importance of sensitive news over time. On days when there are no sensitive news, the coverage of GC outlets would be similar to the coverage of non-GC outlets, and so readers’ demand would be driven by their basic and persistent journalistic preferences and the specific outlet’s brand capital.

On days when there are sensitive news, an additional factor is in play. If on sensitive news days readers change their normal behavior and switch to GC outlets, Simonov and Rao conclude that they do so because they have a preference toward pro-government bias. Conversely, if they move in the other direction, they do so because they have a negative preference toward pro-government bias. If readers are more likely to visit both types of outlets, Simonov and Rao conclude that they are “conscientious,” meaning they see value in being informed on the government’s position.

The demand model Simonov and Rao built suggests that when sensitive news occurs, the majority of Russian readers prefer the coverage of independent outlets. This is true even for consistent readers of government-controlled media, suggesting that their preference, or interest, in independent coverage overrides their preferences for the more enduring characteristics that draw them to GC outlets.

The model also reveals that frequent news readers have more distaste for pro-government bias. At 8.8 percent of the total, these readers are a minority, but they account for 70 percent of total actual consumption. Of these, 40 percent add more ideologically diverse sources to their reading menu when the number of sensitive news increases. This, Simonov and Rao write, suggests that they are “conscientious” readers.

The authors go on to conclude that, since some consumers preferred both the pro-Russia and pro-Ukraine slant in the news coverage of the Ukraine crisis, and infrequent consumers are more likely to have such preferences, and since both types of sources use very emotional language, readers’ preferences are probably driven by the entertainment value.

Simonov and Rao’s study has limitations. They list some of them in the paper: one is that the study ignores all other types of media, such as TV, radio, and print newspapers—and the interactions between them. This is especially important since all three major TV stations in Russia are government-controlled. Ignoring other types of media also ignores co-promotion, such as cross-references between RT’s TV channel and its website.

Another issue is the absence of a supply-side model. Simonov and Rao also do not take into consideration the amount of time readers spend reading each story, which could help assess the degree of information learned. They also assume readers’ preferences stay the same across the sampling period while acknowledging that preferences can change over time.

One major conclusion reached by Simonov and Rao is that for news markets in general—not specifically the Russian market—business interests are not aligned with a goal of creating a news market that will keep readers informed. News organizations, they find, have business incentives to conform to their frequent readers because their consumption drives most of the advertising revenues (which would be irrelevant in Russia, since government subsidies are far greater than ad revenues).

This conclusion may have limitations as well. As Simonov and Rao point out, this assumes that the majority of revenues originate in display advertising and that it is often priced on a cost-per-impression basis. In reality, revenue sources and pricing models are more varied (consider other types such as AdSense, native advertising, outbound links and sponsorships). Also, more and more newspapers charge readers for their online content.

Simonov and Rao correctly point out that consumers can get information from sources other than news sites and that, in their sample, at least 46 percent of consumers navigate to their first news article during the browsing session using links found through news aggregators, search, or social media. But these sources are not only referrers, they also provide news or related information—especially social media. In some respects, they are the dominant players: the Pew Research Center estimates that 62 percent of Americans get their news from social media.

The fact that the Kremlin has gradually increased its influence over the biggest Russian social network, VKontakte (aka “the Russian Facebook”), along with evidence of the extensive use the Kremlin makes of social media for political ends—especially during the Ukrainian crisis—adds considerable weight to this type of media. This might mean that the Kremlin may be responsible for at least some of the basic traffic to GC outlets where there are sensitive news or in their absence. Using the IE’s toolbar dataset, the authors can indeed see consumers visiting social media websites. Some of them are private and therefore the information contained in them cannot be analyzed, but others are open.

Despite its limitations—which are mainly a reason to explore further and deeper, especially when it comes to the roles of social media and TV news—Simonov and Rao provide an in-depth exploration of the news market of a major totalitarian regime, one that is also attempting to influence other nations. Simonov and Rao’s work also provides an excellent background for the Kremlin’s crackdown on independent news sources, which escalated in 2013 and coincided with their sampling period.

Simonov and Rao’s study clearly shows that a majority of Russian readers, including many who share the Kremlin’s ideology, prefer news from sources that are independent or at least partially independent, and possibly implies that they put the quest for truth above their ideologies. This, of course, underscores the role of the open internet as a tool that allows more information to reach readers. At the same time, it may also indicate Putin’s intent to muzzle more sources in order to tighten his grip on Russia’s political discourse.