William Lazonick writes that recent United States industrial policy initiatives miss the centrality of corporate resource allocation for creating a robust economy, characterized by innovation in critical technologies and, through stable and equitable employment, an upwardly mobile middle class. Lazonick argues that a fundamental obstacle to creating a robust economy is predatory value extraction in the form of stock buybacks.

This ProMarket symposium asks how industrial and competition policies can “create a more robust economy” for the citizens of the United States through the injection of federal funding and tailored antitrust regulation to encourage innovation and growth. The implication is that the U.S. economy lacks robustness—a proposition with which I agree. The main problem, however, is not the absence of industrial policy or insufficient competition. The problem is the misallocation of corporate resources through the distribution of trillions of dollars in corporate cash to stock-market traders in the form of open-market stock repurchases—also known as stock buybacks. As I have documented previously, these stock buybacks do nothing to encourage innovation or growth. Rather, this mode of “predatory value extraction” serves to concentrate income among the wealthiest households, whose financial portfolios have increasingly focused on securing income from the stock market, and saddles American workers with unstable employment and inequitable earnings. If American corporations were to forego stock buybacks, their senior executives could instead prioritize investing in the success of their firms and reclaim the missing industrial innovation, job creation, and wage growth that the Biden administration was trying to encourage.

The context of the current debate

A robust economy is one that offers stable and equitable employment opportunities to a growing proportion of its labor force. In a highly productive economy such as the U.S., stable and equitable employment can potentially provide people who possess sufficient productive capabilities with secure earnings over four to five decades of a working life, while permitting them to accumulate assets to support one to three decades of retirement. The offspring of people who experience stable and equitable employment will have upbringing advantages through access to higher education and work experience that, by endowing them with sufficient productive capabilities, can enable intergenerational upward socioeconomic mobility.

In the third decade of the 21st century, the U.S. does not have a robust economy, as I have defined it. According to the Economic Policy Institute, from 1979 to 2020 hourly labor productivity increased by 61.8%, while the real hourly pay of workers grew by only 17.5%. A 2024 Bank of America study found that 26% of U.S. households are living paycheck to paycheck for spending on necessities, including 35% for households with less than $50,000 in annual income. For all too many households, the reality of socioeconomic immobility, if not downward mobility, has transformed the “American dream” into an unattainable fantasy—and often, in reality, a nightmare of making ends meet that they confront, precariously, every day.

Since the 1970s, income has become increasingly concentrated at the top. The 0.1% of households with the highest incomes had an annual average share of reported national income of 9.8% for 1998-2012, a substantial rise from 6.0% for 1983-1997, 3.1% for 1968-1982, and 3.4% for 1953-1967. The richest households accumulate more and more wealth by simply making money out of money. In 1990, publicly traded stocks accounted for 14% of the assets of the top 0.1% of net-worth households; now it is over 44%. In 2023, the 10% wealthiest American households held 93% of the publicly listed shares outstanding, while the bottom 50% held only 1% of the shares.

Value extraction

There are two ways in which the stock market provides yields to shareholders. The first is dividend payments, which provide income to shareholders for (as the name says) holding shares. Dividend payments are socially acceptable sources of income to households that decide to put a portion of their savings into corporate equities. All holders of the same class of shares receive the same income benefit. Note, however, that a company’s dividend payments may be excessive, as is often the case for many European corporations, leaving it with insufficient profits to provide stable employment to its existing workers and invest in the company’s next round of innovative products.

The second way the stock market provides a yield is through stock-price appreciation, which can occur because of a combination of innovation, speculation, and manipulation. Stock-price appreciation often reflects increased demand for company shares when stock traders and asset managers notice that a company has increased its revenues and profits through innovation. Speculation that the stock price will keep rising typically follows a price increase driven by innovation.

However, the senior executives of many publicly listed corporations often allocate vast sums of corporate cash to stock buybacks done as open-market repurchases for the purpose of manipulating the stock price. Whereas a stream of reliable dividend payments encourage shareholders to continue to hold shares while retaining an interest in having the company reinvest a portion of profits in the next round of innovation, stock buybacks encourage shareholders to become shareshellers to realize gains from the manipulative inflation of the company’s share price .

U.S. companies do not disclose the days on which they are doing buybacks. As such, it is only senior executives, many of whom are paid in the company’s shares, and professional stock traders such as hedge-fund managers who have the information on when buybacks are being executed, providing them with the opportunity to time the sale of their shares accordingly. Senior corporate executives can also use buybacks to manipulate quarterly reports, since, all other things equal, buybacks will increase earnings per share, a key financial “performance” metric.

A brief history of stock buybacks

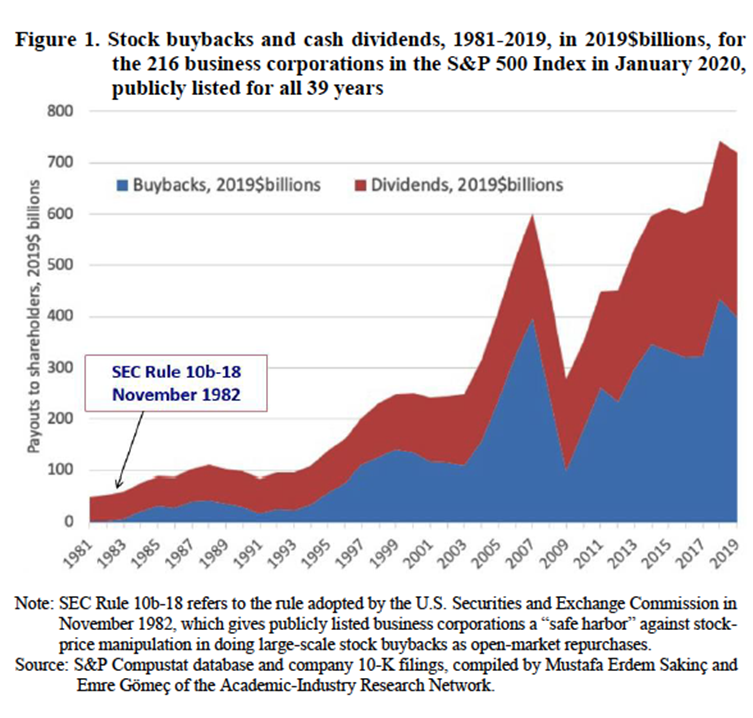

In 1982, the Securities and Exchange Commission adopted Rule 10b-18, which grants a corporation a safe harbor to avoid liability for market manipulation when doing massive stock buybacks. Rule 10b-18 has provided senior executives with what I call a “license to loot” their corporate treasuries. It has enabled U.S. corporations to increase distributions of cash to shareholders, often transitioning from a “retain-and-reinvest” to a “downsize-and-distribute” resource-allocation regime. One consequence has been that the company’s workforce—both blue-collar and white-collar—has become vulnerable to downsizing, even when the company has been profitable.

The 216 companies in the S&P 500 Index in January 2020 that had been listed since 1981 (see Figure 1) distributed around 50% of net income as dividends in both the first and last years of this period. (Net income is a firm’s remaining revenue after all expenses, including taxes, have been subtracted.) However, buybacks soared from 4.4% of net income in 1981-1983 to 62.2% in 2017-2019.

For 2014-2023, the 493 companies in the S&P 500 Index that remained publicly listed during that time distributed $4.9 trillion in dividends (41% of net income) to shareholders and another $6.8 trillion in stock buybacks (57% of net income) to sharesellers.

Most buybacks are done by corporations that have become highly profitable. In 2022, during which companies in the S&P 500 Index did $900 billion in buybacks, the top 10 repurchasers accounted for 28% of the total, the top 25 43%, and the top 50 59%. In that year, the top five repurchasers were Apple with $89.4 billion, Alphabet $30.2 billion, Microsoft $28.0 billion, Meta $28.0 billion, and Exxon Mobil $15.2 billion.

The case of Apple

Consider Apple, historically one of the most innovative and profitable companies in the U.S. During 2021-2024, the company averaged annual profits of $96 billion on revenues of $384 billion, compared with annual profits of $55 billion on revenues of $257 billion in 2017-2020.

From 2013-2024, Apple did the most buybacks of any company by far with $726 billion (93% of net income) on top of $157 billion in dividends (20% of net income). Apple calls these distributions to shareholders its “Capital Return Program.” But the only time that Apple has raised money on the stock market was the $97 million it received in its 1980 initial public offering, belying the claim that it is “returning” capital.

Given Apple’s profitability and innovation, does it matter that the company has averaged over $60 billion in buybacks over the past 12 years? Academic defenders of buybacks contend that a firm has no other opportunities to spend the money used to fund buybacks. An analysis of Apple shows this is hardly the case.

First, consider Apple’s notable lag in investing in artificial intelligence. While competing Big Tech companies in the U.S. and abroad roll out chatbots and other AI software, Apple only released its own AI software in its products in recent months.

But it is semiconductors that provide the best example of how a focus on increasing stock price with buybacks has undermined innovation. Apple first began designing its own silicon chips in its devices in 2020, but since the 2007 launch of the iPhone Apple has outsourced the actual manufacture of its microprocessors, first to Samsung Electronics and then to TSMC, giving both companies the opportunity to become world leaders in advanced nanometer chip fabrication. As I argued in an article that I published in 2013, as Apple was beginning its buyback spree, if Congress had banned these types of buybacks, Apple might have considered more constructive uses of the company’s massive profits, including the design and manufacture of its own chips. Reliance on foreign companies for these components lies at the heart of recent industrial policy in the U.S.

What is notable is that Apple was among the tech companies that in 2021 began lobbying the Biden administration for $52 billion in subsidies to the U.S. semiconductor industry under the CHIPS and Science Act, subsequently enacted in 2022. Yet from 2011 through 2020, Apple and eight of the other companies involved in this lobbying effort, including Intel, IBM, and Qualcomm, had spent $882 billion on buybacks, 17 times the amount of the CHIPS Act subsidies. These companies do not, therefore, lack financial resources to invest in innovation. The problem is that these companies prefer to spend funds on buybacks and then ask taxpayers to foot the bill when America falls behind. In one of our articles on the subject, Matt Hopkins and I ask: Does America want a CHIPS for Buybacks Act?

Failure to invest in innovation and supply chain security is not the only deleterious consequence of Apple’s expensive buyback program. The company could have used a portion of the money used on buybacks to increase the wages and benefits of the tens of thousands of relatively low-paid employees in its Apple stores. And the company could also have provided more cash to support social investment and social innovation. In June 2000, with the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, Apple announced that it would allocate $100 million to a racial justice initiative. That amount was just 0.14% of the $72.4 billion that Apple spent on buybacks in that year. In June 2023, Apple doubled its commitment to the racial justice initiative to $200 million, but in 2021-2023 the company did $253.1 billion on buybacks, compared to which the additional $100 million was just 0.04%. These sums are more than many companies donate, but the proportion of these amounts compared to Apple’s buybacks program makes the company’s priorities clear.

Instead, Apple’s buybacks have contributed to the extreme concentration of income among the richest households. In 2016, Carl Icahn raked in $2 billion in profit when he sold Apple shares that he had bought for $3.6 billion in 2013, after, pressured by Icahn, Apple did record-breaking buybacks in 2014 and 2015. As of June 30, 2024, Warren Buffett, on behalf of Berkshire Hathaway, had a net gain of $158 billion on $39 billion in Apple shares that he had begun buying on the market in 2016. During this time, Apple averaged over $69 billion in buybacks and $20 billion on research and development annually. Not one cent of the cash that Icahn and Buffet used to purchase Apple shares flowed to the company for investment in productive capabilities or any other purpose.

To say that Icahn and Buffett pressured Apple to executive record-breaking buybacks should not misconstrue Apple’s management as unwilling participants. In 13 years as Apple CEO from 2012 to 2024, Tim Cook reaped total compensation of $707 million (averaging over $54 million per year), of which 78% was realized gains from the vesting of stock awards. In 21 years on Apple’s board after joining in 2003, Albert Gore Jr. accumulated $122 million ($35 million realized) from Apple shares granted as the lion’s share of his director compensation.

Corporate financialization is harming America’s economy

Apple is only one example that contradicts the arguments that the fundamental problem for robustness of the American economy is insufficient competition or a lack of government funding. For another example, Intel is a laggard in advanced semiconductor fabrication, not because of a lack of U.S. industrial policy, but because its four CEOs from 1998 through 2020 did $142 billion in buybacks and, as Hopkins and I have explained, stumbled in implementing advanced nanometer nodes for chip fabrication. CEO Paul Otellini (2005-2012), a finance guy who executed $46 billion of those buybacks, turned down Apple’s offer in 2007 to supply its iPhone chips. Instead of wasting $22.7 billion on buybacks in 2004-2006, Intel could have taken up the opportunity to buy Nvidia (which now has a market cap of about $3.0 trillion) for $20 billion in 2005. When, in February 2021, Intel recruited Pat Gelsinger, a production guy, as CEO, a condition of his acceptance was no more buybacks. In a very difficult competitive environment, Gelsinger grappled with the legacy of Intel’s financialized past, until the Intel board forced him to resign as CEO on December 1, 2024.

Research by the Academic-Industry Research Network documents that, as in semiconductor fabrication, buybacks bear substantial blame for the U.S. lag in global competition in a number of critical technologies including electric vehicle batteries, communications equipment, and aviation. Pharmaceutical companies contend that they need high (unregulated) prices in the U.S. on existing approved drugs to fund the next round of drug innovation. But the data reveal that many of the major U.S.-based pharmaceutical companies devote all or more of their profits to distributions to shareholders to boost their stock prices.

The economic problem is not a lack of product-market competition. Government intervention may be warranted when it involves monopsony in labor markets or supply chains and when there is overt price fixing or price gouging. Given corporate financialization and a pervasive ideology that prioritizes yields to sharesellers, however, antitrust policy alone cannot create a robust economy.

Large corporations dominate the U.S. economy. In 2021, 517 business corporations with 20,000 employees or more in the U.S., and an average of 61,244, accounted for 24.7% of business-sector employment and 26.6% of payrolls. The resource-allocation decisions of these giant corporations have a preponderant influence on investment in productive capabilities as well as the quantity and quality of employment opportunities available in the U.S. economy. If the primary focus of corporations is allocating their resources to stock buybacks rather than investing in innovation, U.S. industrial policy will fail as the companies fall behind in global competition.

How could the incentives for industrial enterprises be improved? In Investing in innovation: Confronting Predatory Value Extraction in the US Corporation, I lay out a five-pronged corporate-governance policy agenda for enabling the U.S. economy to provide stable and equitable employment opportunities to the members of its labor force:

- Ban stock buybacks as open-market repurchases by rescinding SEC Rule 10b-18.

- Compensate executives for contributing to value creation, and not for value extraction.

- Reconstitute corporate boards to include directors who represent workers and taxpayers while excluding predatory value extractors.

- Reform the tax system so that it supports investment in productive capabilities.

- Use corporate profits and government taxes to fund collaborative investments in productive capabilities that can enable American workers and their families to access stable and equitable employment opportunities, with an emphasis on mobilizing their skills and efforts to solve the nation’s existential climate, health, and security crises.

The discussion of how to conjoin antitrust and industrial policy is important but misses the real obstacles to boosting employment and innovation in key sectors. Misguided “regulation” of stock buybacks creates incentives among the C-Suite and hedge funds to extract corporate profits for themselves and underinvest in innovation and employees. Any industrial policy that does not respond to predatory value extraction will only send tax-funded subsidies into the pockets of billionaires, rather than achieve a more resilient, competitive, and equitable economy for all.

Author Disclosure: William Lazonick is president of the Academic-Industry Research Network. Funding for the research that underpins this article has been provided by the Institute for New Economic Thinking and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research. The author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.