The United Kingdom has struggled to implement long-term industrial policies in recent decades, writes Diane Coyle, a trend the new Labour Party promises to reverse. She describes the policy proposals and the skepticism surrounding their current state of implementation. With major shifts on the horizon, namely artificial intelligence and energy, the Starmer government’s ability to execute on industrial policy for the country is critical.

Depending on how you look at it, the United Kingdom has either had many industrial policies or none worth the name during the past 40-odd years. Many plans and frameworks have been launched only to survive for, at best, a few years. The government of Keir Starmer, the country’s first Labour administration since 2010, has made clear its intention to introduce a long-term framework for industrial policy. But any evaluation of this intention needs to start with the legacy that he and Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves inherited from the Conservatives after winning the 2024 general election on July 4.

This recent history begins with Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s market-oriented shift in economic philosophy following her 1979 election. The 1970s had been a traumatic decade in the U.K., with a particularly severe recession and high inflation (by international standards) following the oil crises, and dreadful government-employer-union relations manifested in multiple strikes in what became known as the Winter of Discontent. This traumatic experience – featuring mountains of rubbish in the streets, hospitals dealing only with emergencies and a halt to burials – paved the way for Thatcher and her successor, John Major, to dismantle the National Economic Development Office (known as “Neddy”), the body overseeing tripartite industrial policy discussions, alongside the introduction of a program privatizing formerly state-owned businesses and deregulating the financial markets.

Perhaps because of its singularly bad 1970s experience, the U.K. stands out among its comparators for its adherence to market solutions rather than industrial policy throughout the following decades. The notion of industrial policy encompasses a wide variety of policy levers, and of course these were never abandoned. Interventions such as tax breaks for capital investment or patentable activities, government funding of basic research, infrastructure investment, support for specific sectors like film or regulatory reform of markets like electricity continued through successive governments. However, the notion that the government should have a strategic approach to key sectors with sustained interventions—as in many East Asian economies or in countries such as France and Germany—never took hold among most political and official decision makers.

This meant that although there were periodic attempts to introduce an industrial policy (by New Labour in 2009, by the coalition government in 2012, and by Theresa May’s Conservative government in 2017), all were short-lived. These and various other economic policy documents generally highlighted the same U.K. strengths to nurture industry (Table 1), but the policies introduced changed considerably between administrations. What’s more, all the policies were centrally devised and implemented, lacking a solid foundation of knowledge about potential pitfalls such as local skill shortages or inadequate infrastructure.

Industrial policies in recent times have therefore exemplified well-known failures of U.K. statecraft: policy churn, and lack of coordination across departmental silos or national and local government. Government policies in the U.K. have done the opposite of what a good industrial policy would do, by increasing rather than decreasing the risk faced by businesses and investors.

Table 1: Sectoral focus in successive UK governments’ economic policies

| New Labour 2008 | Coalition 2012 | May 2017 | Johnson 2021 | Labour 2024 |

| Life Sciences/Pharmaceuticals | Advanced manufacturing (Aerospace, automotive, life sciences) | Life Sciences | Space | Life sciences |

| Aerospace & defence | ||||

| Advanced manufacturing | Automotive | Automotive | ||

| Professional Services/Finance | Knowledge-Intensive services (finance, information services, higher education) | Creative sector | – | Financial services |

| Creative sector | ||||

| Net Zero (low-carbon vehicles) | Energy | – | Net zero/energy | “Mission” to be a “clean energy superpower” |

| Engineering Construction | Construction | Construction | – | – |

| Digital | – | AI | AI | AI |

Source: Coyle & Alayande, International Productivity Monitor forthcoming.

As Table 1 indicates, the current Labour Government has identified many of the same priority sectors as its predecessors, typically characterised by high levels of value added and/or net exports. In parts of two—life sciences and artificial intelligence—U.K. universities and institutes can rightly claim to attain the research frontier. However, it frames its approach to industrial policy in a novel way, in terms of national “missions.” Only one of these is solely economic, the ambitious mission to “Kickstart economic growthto secure the highest sustained growth in the G7—with good jobs and productivity growth in every part of the country making everyone, not just a few, better off,” Within the lifetime of the current parliamentOthers—to be a clean energy “superpower,” enhance opportunities by reforming education, and future-proofing the National Health Service—overlap with areas of industrial policy such as green investment.

Three of the five missions have no specific target date (the other exception being a 2030 target for zero carbon electricity generation), so they should be interpreted as rhetorical devices to overcome the long-standing lack of coordination and instability in policymaking. The Labour election manifesto stated:

Our approach will be mission-driven and focused on the future.[…] Critically, we will end short-term economic policy making with the establishment of an Industrial Strategy Council, on a statutory footing, to provide expert advice. We will ensure representation on the Council from all nations and regions, business and trade unions, to drive economic growth in all parts of the country.

As I write, the details have yet to be announced.

In addition to mentioning some sectoral strengths, the policy statements mention “horizontal” policies, again with an emphasis on longer-term horizons and stability—such as reforming planning laws, modernizing the transport network, keeping corporate tax rates low and stable, stimulating investment through creating a “National Wealth Fund” (an investment vehicle rather than a wealth fund), and introducing long term budgets for research institutions.

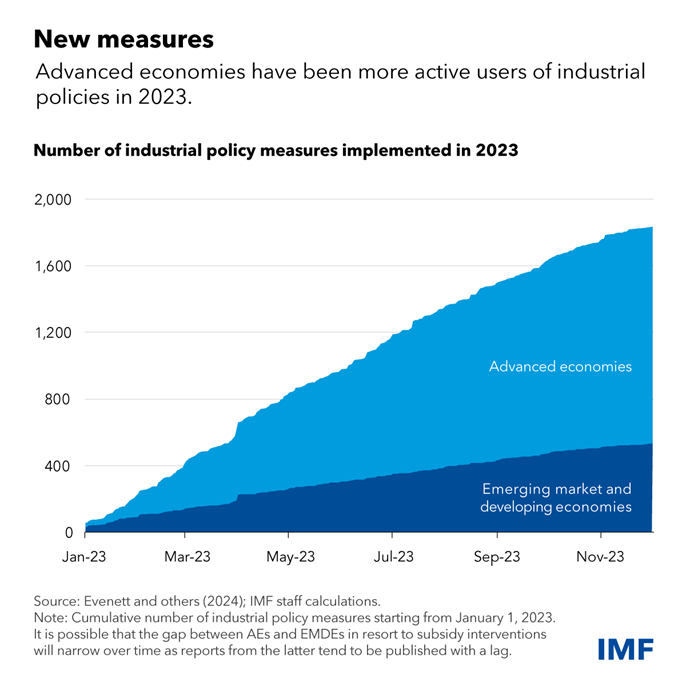

Given the U.K.’s depressing record of low investment and productivity growth— again, among the worst in its peer group since the financial crisis—it would be difficult to find economists who disagree with much of this agenda. It helps that the international climate with regard to activist industrial policies has changed so much: as figures on the number of industrial policy interventions indicate, this has become the new normal (Figure 1) and even the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has cautiously welcomed this shift. The examples of the Biden administration in the United States are much discussed in U.K. policy circles.

Figure 1:

However, the Government is just over a month old, so it is too early to evaluate how well it will implement its intentions or what the likely impact on economic growth might be. Critics point to some early decisions that have dismayed the sectors concerned.

In August, the government cancelled the 1.3 billion pounds its predecessor had earmarked for technology and AI projects, including an expanded supercomputer facility. After the backlash this prompted, unnamed officials claimed the Conservatives had not funded the prior plans so the aim would be to focus any government investments and fully fund them. It has commissioned entrepreneur (and chair of research agency ARIA) Matt Clifford to produce an “AI Action Plan” by the end of September. While the case for strategic focus is well understood, the reversal has raised anxieties in the sector.

Another example is a reported decision to reopen discussions about the level of subsidy the previous Conservative government had promised to pharma company AstraZeneca: 50 million pounds for research and 40 million pounds for vaccine development. The company is said to be considering moving its facility at Speke, in the deprived Merseyside area, to Philadelphia for the more generous incentives it claimed were on offer in the U.S. No doubt there are negotiating tactics involved on both sides, as ever when it comes to taxpayer support, but AstraZeneca is a key player in the U.K.’s life sciences sector so any such decision would be a big blow.

These examples point to an unavoidable paradox faced by the government: it rightly wants to establish a more consistent and coordinated industrial policy framework, and yet it wants to unpick many of the decisions and policies inherited from its predecessor. Change is a pre-condition for stability. In any case, it will soon experience the pain of moving from the general statements in the manifesto and early policy announcements to the tough decisions that are inevitable when it comes to implementation. The tight fiscal arithmetic, and an October Budget expected to introduce tax increases, will increase the pain.

The Labour government’s economic inheritance is unenviable. Trend growth is slow, and the public finances are tight, while private and public investment will have to increase substantially if this is ever to change. The economy is among the most unequal in the OECD, many public services including in local government are failing, and the harmful impact of Brexit continues to drag on trade.

Globally, two major structural transformations are under way, in energy and in AI, making decisions affecting the supply side taken now critical for economic performance for decades ahead. A strategic industrial policy is without doubt an improvement on the previous churn, especially in a context where all the U.K.’s economic peers are further ahead in making this policy shift. Much rides on the actions the Starmer government takes in the coming months.

Author’s Disclosure: The author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.