Reviewing the literature pioneered by Richard Gilbert and David Newbery, Steven Salop finds that the recent settlement between sports-streaming services Fubo and the Venu Sports joint venture of Disney, Fox, and Warner Bros. Discovery was fully predictable. But the settlement takes on greater complexity in light of the termination of joint venture a week later and the new Disney/Fubu combination.

In February 2024, Disney, Fox and Warner Bros. Discovery announced the creation of a sports-streaming joint venture that they named Venu Sports. Subscribers to Venu would have access to traditional broadcast sports networks, including content from Disney (ESPN, ESPN+, ESPN2, ESPNU, SECN, ACCN, ESPNEWS, and ABC), Fox (FOX, FS1, FS2, BTN) and Warner Discovery (TNT, TBS, and truTV). On August 1, 2024, the parties announced that the first-year price of Venu would be $42.99, with an expected rollout sometime that fall.

There were two flies in this sports-streaming ointment. First, it was reported that the Department of Justice (DOJ) was investigating the joint venture, recalling that the DOJ blocked the analogous Premiere movie joint venture in 1980. Second, even before the end of February 2024, Fubo TV, a “sports-first” streaming service, filed a preliminary injunction action in the Southern District of New York that the joint-venture streaming service would limit competition and raise prices. This second fly bit hard on August 16 when the court issued a preliminary injunction that the parties quickly appealed.

But there is more than one way to swat away a pesky fly. On January 6, 2025, one hour before the oral argument for the appeal, the parties announced a settlement whereby Fubo would drop its lawsuit against Venu and the companies, and the media companies would withdraw their appeal. In exchange, the three media companies would make a cash payment to Fubo of $220 million and Disney would provide a $145 million loan to Fubo in 2026. And most notably, Fubo and Disney would create a new merged entity combining Fubo with Disney’s Hulu+LiveTV service. The entity would be owned 30% by Fubo and 70% owned and controlled by Disney. Fubo would continue to offer its separate streaming service, including a sports and broadcast service featuring Disney sports content.

Less than a week after the settlement, Disney, Fox, and Warner Bros. Discovery announced they were ending their joint venture. This raises another mystery: why would the companies terminate Venu after successfully settling with Fubo?

Economic analysis of rent-sharing settlements

Economic analysis predicted a settlement of this case. For example, Erik Hovenkamp and I have provided a rigorous analysis of “rent-sharing” settlements and why they are often anticompetitive. Indeed, this settlement might be seen as a natural experiment of that theory.

When there is litigation attacking a firm attempting to achieve or maintain monopoly power (or, more generally market power), the parties have a shared interest in striking anticompetitive “rent-sharing” settlements before a final irreversible judgment that would reduce or eliminate that market power. In these settlements, the defendant provides cash or other valuable consideration in exchange for eliminating the plaintiff’s continued pursuit of the final irreversible outcome. For example, a dominant firm would pay a large lump sum to the plaintiff-rival in exchange for letting the defendant’s conduct continue in full. Such an agreement would be unlawful if the court ultimately issues a final judgment for the plaintiff. But before that point, when the ultimate outcome of litigation is still uncertain, the legality of such a deal may be more ambiguous.

Pharmaceutical company Actavis’ attempted “pay for delay” patent settlement, struck down by the Supreme Court in 2013, provides one well-known example of such rent-seeking settlements. In a pay-for-delay settlement, a patent monopolist pays off a prospective entrant who is challenging the patent’s validity in court. The deal gives the challenger a large lump sum (a so-called “reverse payment”) in exchange for abandoning its challenge and staying out of the market until the patent is about to expire. The Court held that this kind of settlement is usually illegal (albeit not illegal per se) because, whereas litigation offers the possibility of invigorated competition, a pay-for-delay settlement extinguishes that possibility. In other words, the settlement harms consumers, relative to the expected result of litigation.

The incentive for rent-sharing settlements arises from the litigants’ asymmetric stakes in the dispute. As a general matter, a monopoly can earn greater profits than multiple firms can earn in aggregate in a more competitive market. For this reason, there is room for a deal. The dominant firm can afford to fully compensate the plaintiff for the profits the plaintiff would earn in the competitive market that would arise if the plaintiff won in court—and still have profits left over for itself. This analysis of asymmetric stakes is just another application of Richard Gilbert and David Newbery’s seminal study modeling R&D competition. The same model can also be applied to litigation efforts with asymmetric stakes, competitive bidding to acquire potential competitors, counterstrategies to avoid exclusionary conduct, and even possible remedial provisions in U.S. v Google.

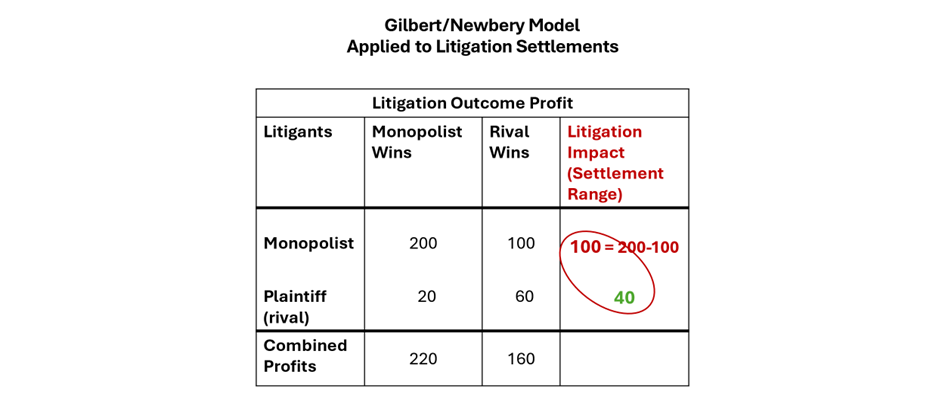

This implication of litigation with asymmetric stakes can be illustrated with a numerical example. As shown in the payoff matrix below, where the entries are the net present value of profits, suppose that a victory in court for the dominant firm would lead it to profits equal to $200 while the plaintiff would have profits of only $20. But in contrast, if the plaintiff obtains a final judgement in its favor, the dominant firm’s profits would be only $100 while the plaintiff’s profits would be $60. Suppose the litigants share a common expectation that the plaintiff will win the case with certainty. Under these circumstances, the plaintiff would be willing to accept a settlement in excess of $40 (expected profits ($60) minus current profits ($20)) to terminate the litigation. After the settlement, the dominant firm would end up with profits somewhat less than $160 (i.e., expected profits under monopoly conditions ($200) minus the settlement payout to the plaintiff ($40)). Thus, they have mutual incentives to settle the litigation before it is finalized with a judgment for the plaintiff as long as the settlement amount is anywhere between $40 and $100.

The key factor that drives this result is the fact that the total profits for the two litigants are higher when the monopoly is maintained. In the example, this is the case. The total profits are $220 (i.e., $200+$20) when the monopoly power is maintained versus only $160 (i.e., $100+$60) when there is competition. This is not surprising. Competition typically causes consumer welfare to rise while sellers’ profits fall. It is not inevitable for competition to decrease total profits. Profits can increase when the plaintiff has lower costs or a significantly differentiated product. But in the more typical case where there is litigation between rivals, total profits will fall.

The example above assumed that the plaintiff would prevail in the litigation with certainty. But it is important to stress that this result does not require certainty. Suppose instead that the litigants had a common expectation that the plaintiff would win with a probability of 60%. In that case, their expected profits absent a settlement would be a weighted average of the two possible outcomes of the plaintiff winning or losing. That is, the expected litigation profits for the defendant would be $140 (i.e., 0.60*100+0.40*200). For the plaintiff the expected litigation profits would be $44 (i.e., 0.60*60+0,40*20). In this example, the defendant’s expected gains from a settlement that retains its dominance is $60 (i.e., $200-$140). The plaintiff’s gains from continuing to pursue the litigation are now only $24 (i.e., $44-20). Thus, there is mutual benefit from a settlement that pays the plaintiff more than $24 but less than $60.

Vacatur and collateral estoppel

Rent-sharing settlements can have additional anticompetitive effects. When parties engage in these settlements after an initial judgement, they may ask the trial court to vacate its judgment. That vacatur would prevent third parties from relying on the judgment (via collateral estoppel) as a basis for obtaining relief in their own follow-on lawsuits. However, following the Supreme Court’s Bonner Mall decision, courts now routinely refuse vacatur requests when there are third parties who could rely on the judgment in follow-on litigation. In effect, the Court’s decision treats the collateral effects of a judgment as a public good that the litigants have no right to destroy. In this matter, the parties stated that the settlement “extinguished” the preliminary injunction. But both EchoStar and DirecTV have asked the court to refuse to vacate its factual and legal findings.

Competitive effects analysis of the sports-streaming settlement and the aftermath

Even if the preliminary injunction were vacated, that might not have affected the outcome of the DOJ’s antitrust analysis. The original joint venture combined three media companies that control a substantial share of sports programming. The settlement did not eliminate the underlying competitive concerns about the Venu owners jointly controlling the distribution of more than a 50% share of sports rights, though it was suggested that Venu could not succeed without the NFL and more NBA games. In this regard, the parties argued that each would continue to compete independently with separate streaming services. They also planned to continue to independently license their content to other distributors, albeit while providing most-favored nation status to Venu, meaning no other distributor would receive more favorable contractual provisions. However, the profit-sharing within the joint venture would have affected these unilateral incentives to compete as indicated in Guideline 11 of the 2023 Merger Guidelines and the partial ownership literature. In addition, the parties presumably set the joint venture price and terms cooperatively. In the end, the DOJ’s analysis of these issues would be the likely determinative factor. Thus, even if the settlement is treated as neutral, the joint venture itself could still violate Section 7 of the Clayton Act. In fact, the DOJ filed an amicus brief in support of Fubo in the now-withdrawn 2nd Circuit appeal.

Moreover, adding Fubo into the venture could increase the competitive concerns. Fubo would be merged with Disney’s Hulu+LiveTV, though both services were to be continued. However, whereas Fubo previously was an independent sports streaming competitor, it would have now been 70% owned and controlled by Disney, despite the fact that it apparently would have been run by the old Fubo management team. This would appear to increase the incentive to raise the prices of Fubo and Venu, if not also Hulu+LiveTV. Disney’s incentive to push for higher Venu prices also might be enhanced. Elimination of double marginalization (EDM) benefits might have been complicated by the thicket of most-favored nations provisions in pay-TV contracts.

Another possible twist on EDM is that Fubo would have needed to purchase content from Disney. If Disney were to raise the content fee by $10, the net effect of Disney’s 70% ownership share would have Fubo stockholders pay $3 dollars more while the other $7 would simply have flowed from one Disney pocket to another. So if Disney wanted to emasculate Fubo as a competitor of Venu, it had a simple mechanism to do so. Indeed, one commentator referred to the settlement as “catch and kill.” By contrast, if Fubo would have been too weak to have any independent competitive effects absent the settlement, then the analysis would be more complex. This is because a differentiated Fubo service may have incremental value to consumers, a value that might have been lost absent the settlement.

But this raises another question. If the antitrust risks remained so high, then why not simply abandon the joint venture rather than spend the money to settle with Fubo? One possible factor is that Fubo was also attacking the parties pre-merger conduct, including bundling, penetration restraints, and exclusionary high content prices. But another answer might recall Doctor. DeSoto: the mouse outfoxing the fox. Disney might now replace Venu with Fubo while escaping the overhang of the broader horizontal concerns. The best-case scenario would be unpublished settlement terms requiring Fox and Warner Discovery to provide content to Fubo at low prices and without the other restraints.

It will be interesting to see how the drama develops further. The Disney/Fubo transaction is still a horizontal-plus-vertical acquisition that raises potential competitive issues. Disney’s partial but controlling ownership raises some additional complexity. The DOJ is unlikely to see it as innocuous. Indeed, in the extreme, the Fox and Warner Discovery content contracts might be cleverly structured to nearly replicate the profit-sharing and incentives of Venu.

Afterword: Asymmetric litigation efforts and skewed judicial outcomes absent settlement

While not directly relevant to the analysis of this settlement, readers also might be interested in better understanding the distortions caused by the asymmetric stakes in litigation outcomes when rent-sharing settlements are prohibited. As explained in the Hovenkamp/Salop article, the asymmetric stakes can lead to inefficiently skewed trial outcomes. This additional application of Gilbert and Newbery occurs because the defendant-monopolist’s greater financial stakes than the plaintiff-rival’s lead to the defendant engaging in a higher level of litigation effort. This will tend to lead to the court seeing relatively more evidence favorable to the defendant than is warranted by the merits. If the court does not account and adjust for this effect, the firms’ asymmetric stakes will generate a downward bias in the plaintiff’s winning probability, relative to the merits. In other words, litigation outcome probabilities will be systematically skewed in defendants’ favor, which will lead in turn to under-deterrence. An efficient legal system could mitigate this distortion by reducing the evidentiary burden imposed on plaintiffs either by adjusting the standard of proof or applying an anticompetitive presumption.

Author Disclosure: Steve Salop is Professor of Economics and Law Emeritus, Georgetown University Law Center and Senior Consultant, Charles River Associates.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.