New research from Carlo Medici shows how mass immigration to the United States in the early 20th century spurred union growth.

Labor unions have long been core institutions in the labor markets of advanced economies. Throughout the 20th century, they played a crucial role in reducing inequality, improving working conditions, shaping public policy, and influencing political systems. Despite fluctuations in membership, unions remain pivotal today. In 2023, 539,000 workers participated in work stoppages in the United States—a 141% increase from the previous year—and 70% of Americans currently approve of unions, one of the highest rates in the past 90 years.

Yet, empirical evidence on the historical forces behind the emergence and growth of organized labor remains limited. My recent paper, Closing Ranks: Organized Labor and Immigration, examines how the mass immigration of Europeans to the U.S. during the early 20th century influenced the development of labor unions.

The impact of immigration on unions is not straightforward. On the one hand, increased job competition could push workers to unionize, seeking protection against threats to wages and employment. On the other hand, a larger labor supply might allow employers to replace striking workers more easily, undermining unions’ bargaining power. My research addresses this ambiguity and asks: did immigration help or hinder the rise of American labor unions?

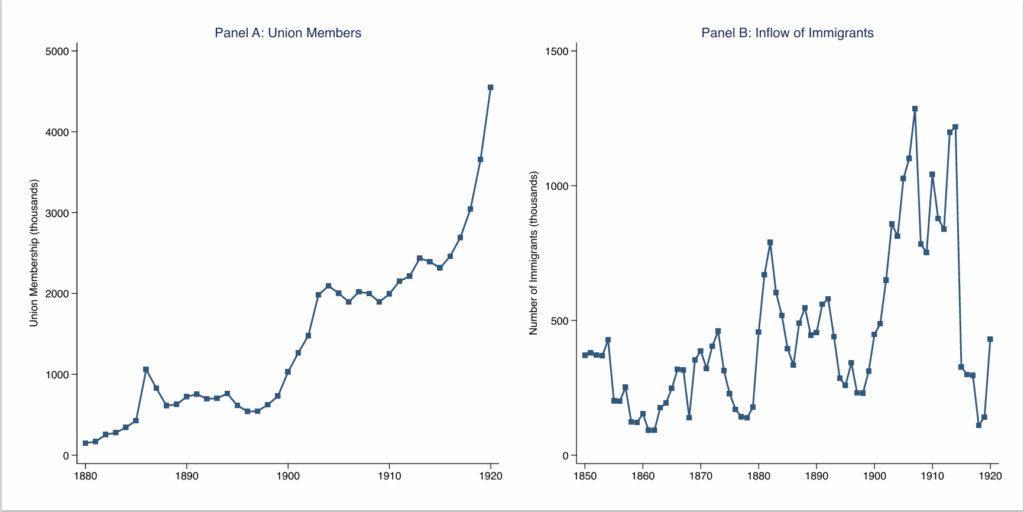

The early 20th-century U.S. offers an ideal setting to study this question. By 1900, the U.S. economy was the largest in the world, and the labor movement was experiencing its first national expansion. Many unions that emerged during this period remain influential today. This growth occurred despite significant challenges to union organizing, as the legal framework allowed employers to dismiss or replace unionizing and striking workers with ease. Immigration played a central role in shaping these dynamics. Between 1850 and 1920, around 30 million European immigrants entered the U.S., creating both opportunities and challenges for organized labor (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

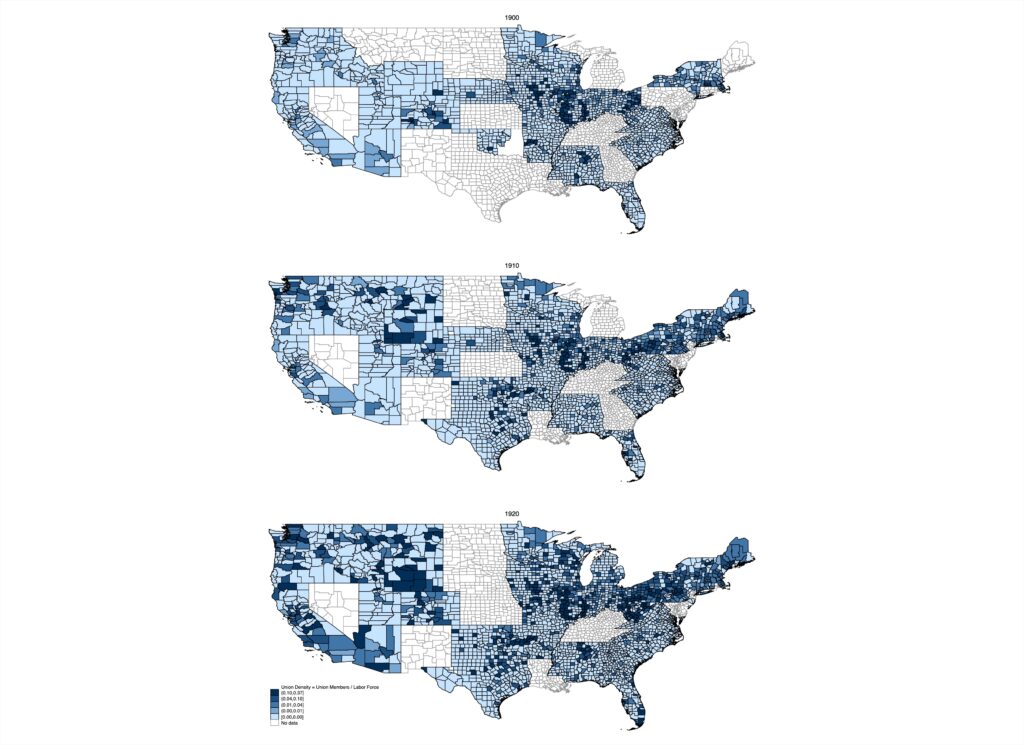

To measure union activity, I digitized convention proceedings of state federations of labor, which are the state-level organizations of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). AFL unions represented over 80% of union members nationwide during this period. These data provide the first comprehensive, local-level measurements of historical union presence and density in the U.S. (Figure 2). To estimate the causal impact of immigration between 1890 and 1920 on unionization, I employed a shift-share instrumental variable, leveraging the pattern of chain migration, where immigrants often settle in areas with established communities from their country of origin.

Figure 2.

Key findings

The findings reveal a clear pattern: immigration fueled the growth of organized labor. Counties with larger immigrant inflows as a fraction of the population experienced significant increases in union presence, number of union branches, share of unionized workers, and average branch size. Immigration spurred unionization both with the formation of new unions and the growth of existing unions. For every 100 immigrants entering the average U.S. county, union membership increased by nearly 20 workers. Without immigration, the average union density (i.e., the share of unionized workers) between 1900 and 1920 would have been approximately 22% lower.

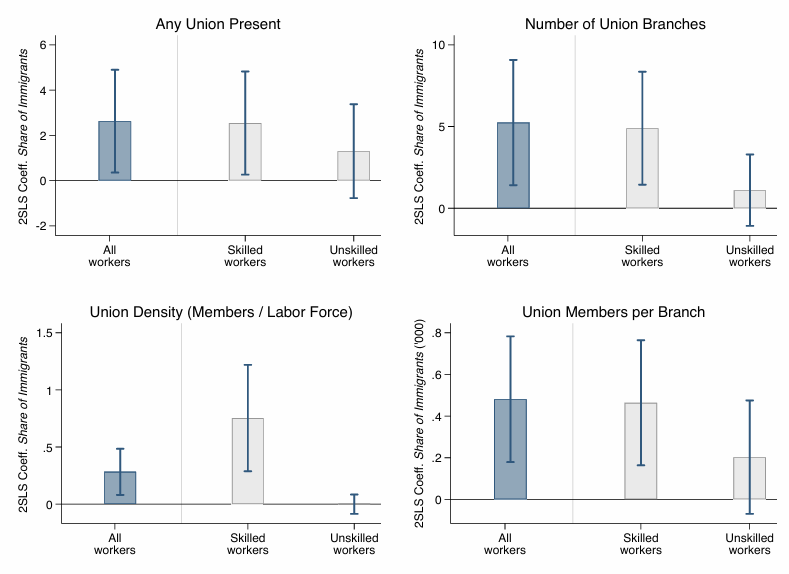

Yet the impact of immigration on unionization was not uniform across all workers (Figure 3). Skilled workers, such as those in craft occupations, responded by organizing to protect their jobs and wages. Their specialized skills acted as barriers to entry, making them not immediately replaceable and enabling them to form or join unions. This allowed them to exclude new workers from the labor force and prevent them from acquiring the skills required for these jobs. In contrast, low-skilled workers such as laborers, whose jobs could be easily filled by newcomers, faced reduced bargaining power and struggled to sustain unions. The coefficients shown in the figure indicate that the effect of immigration on the unionization of skilled workers was positive, while it was smaller and not statistically distinguishable from zero for unskilled ones.

Figure 3.

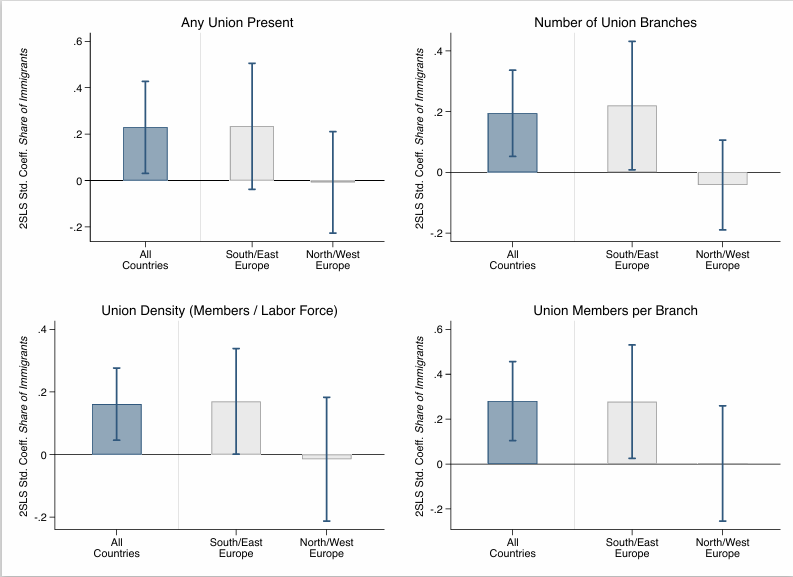

Alongside economic motivations, social factors also likely played a role. AFL unions often adopted nativist rhetoric, portraying immigrants—especially those from Southern and Eastern Europe—as culturally distant and less likely to assimilate into American society or unionize effectively. These attitudes were reflected in unionization patterns. Counties receiving more immigrants from culturally distant regions saw greater increases in union activity (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

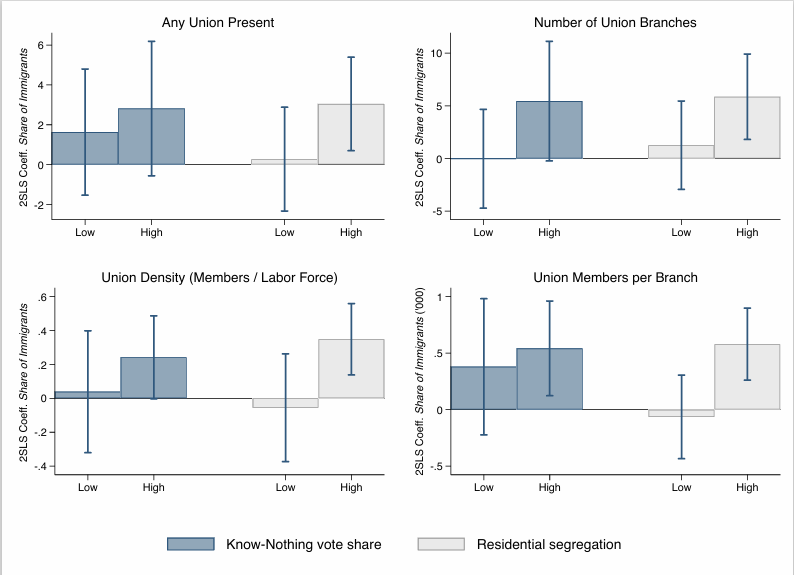

Union growth was also more pronounced in areas with higher resentment towards immigrants, as measured by historical support for the Know Nothing Party and baseline levels of residential segregation between U.S.-born individuals and European immigrants (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

It is important to note that these last two sets of results are also consistent with economic explanations. Immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe likely had lower wage expectations than those from Northern and Western Europe, making them more likely to be perceived as a threat to existing workers’ conditions. Moreover, fears of economic competition from immigrants may have amplified negative stereotypes and reinforced pre-existing resentment. Overall, the evidence supports the role of both economic and social factors in driving organized labor’s observed growth.

Alternative explanations, such as immigrants disproportionately joining unions or bringing radical ideologies from their home countries, are not supported by the data. The results are also not driven by other major events during this period, such as the political and economic transformations caused by World War I and the First Red Scare, or by differential economic growth experienced by counties receiving larger shares of immigrants.

Long-term implications

The effects of early 20th-century immigration on unionization extend beyond the historical period studied. Counties that received more immigrants between 1890 and 1920 continue to exhibit higher union density today. This suggests that the institutional foundations established during this era provided lasting advantages for organized labor, shaping labor market dynamics for over a century.

The study also highlights immigration’s broader economic implications, showing that it increased the share of U.S.-born workers in unionized jobs. The evidence is consistent with native-born workers gravitating toward unionized occupations as a refuge from labor competition posed by immigrants.

Conclusion

This research identifies immigration as a critical driver of unionization during the formative years of the American labor movement. By examining how immigration shaped the growth of organized labor, the study provides new insights into the economic and social forces that influence labor market institutions. These results also broaden our understanding of the consequences of immigration, showing that individuals’ responses to large immigrant flows are not limited to supporting conservative parties or anti-immigration policies, as emphasized by prior research. Immigration can also foster the growth of organizations with broad political and economic impacts, such as unions, with lasting effects into the present.

While the historical context is unique, the findings underscore broader mechanisms that remain relevant today. Renewed interest in unions may reflect workers’ responses to modern labor market pressures, such as immigration, globalization, and technological change. These dynamics are not limited to the U.S. They resonate with advanced economies facing similar challenges and with industrializing nations undergoing economic transformations comparable to early 20th-century America.

Further research is needed to explore how organized labor responds to economic shocks across different contexts. The dataset assembled for this study also offers opportunities to investigate additional questions, including the long-term consequences of early unionization on immigrants’ integration and its broader impact on the U.S. economy and political landscape.

Author Disclosure: the author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.