Steven C. Salop argues that as part of any remedy outcome from the Google Search case, Google cannot be permitted to enter agreements with web browser operators such as Apple to share ad revenue from online searches, even without the condition of setting Google Search as the default choice. To do so would continue to create the same incentives to entrench Google’s position in the search market as did Google’s anticompetitive exclusive distribution agreements.

It might be claimed that Google’s conduct in the Google Search case would not have violated antitrust law if it had merely paid unconditional revenue shares to search distributors—via web browsers—like Apple and others, that is, payments which were not conditioned on Google Search being made the exclusive default search engine. This claim is invalid. These agreements would violate both Section 1 and Section 2 of the Sherman Act. Even if there are no all-or-nothing defaults, or only a few, the payments can still provide powerful incentives to distributors to direct searches to Google. They are still payments (albeit indirect) for exclusion which raise anti-competitive barriers to entry and expansion. If there are some exclusive defaults, unconditional revenue-sharing payments on other searches would exacerbate the exclusionary effects. Absent Google providing sufficient rebuttal evidence that the payments and associated monopoly power of Google increase overall consumer welfare from search, the unconditional payments should be prohibited.

This analysis is also relevant for remedy design. It explains why the Google remedy should not permit Google to engage in unconditional revenue-sharing during the interim period until effective competition is restored.

Monopolization with all-or-nothing exclusive defaults

Google was found liable for its exclusive defaults with search distributors like Apple and others that were negotiated on an all-or-nothing basis. These amounted to exclusive dealing contracts. Google set the prices of search advertising, not the distributors, so there was no scope for price competition in the relevant search advertising market. The search distributors earned a share of the monopoly advertising revenue. The combination of the exclusivity and revenue-sharing practices deterred competitive expansion by rivals.

A rival would have the incentive to try to induce search distributors to forgo the monopolist’s exclusivity agreement by offering a revenue-sharing or other payment to use its search engine, either exclusively or non-exclusively. It is theoretically possible that a rival could succeed if its search product is substantially superior for many consumers.

However, following the seminal analysis of the Gilbert/Newbery model, a rival’s counterbidding faces a severe impediment: the monopolist’s value of maintaining monopoly profits exceeds the rival’s value of earning duopoly profits. Monopoly profits generally exceed the sum of the duopoly profits because the competition leads to lower prices. This difference is reinforced if the rival has higher costs and must invest. In addition, duopoly competition may lead the monopolist to invest in better product quality, which will also tend to reduce the profits of both firms.

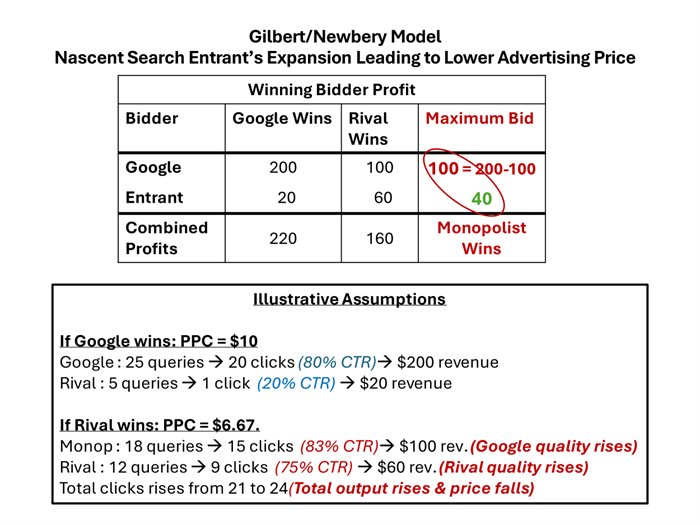

Google’s ability to maintain monopoly power and deter competitive expansion by outbidding a nascent entrant (or fringe competitor) for exclusive rights is illustrated below. If the rival firm were able to expand adoption of its search engine, it would obtain more search queries and its higher scale would increase its quality and click-through rate (“CTR”) on queries, for example, by more effective ad targeting. The advertising price per click (PPC) would fall due to the increased competition. In response to the increased competition, Google also might invest more, which would improve its own CTR. Thus, competition would lead to high output (i.e., more clicks) and a lower market price per click (PPC). However, as the example below illustrates, Google is able to deter the competition and maintain monopoly power by acquiring exclusive defaults.

In this example, in a bidding contest, the rival’s maximum bid would equal its total duopoly profits i.e., $40. In contrast, Google would be willing to bid up to the difference between its monopoly and duopoly profits i.e., $160. Given this difference, Google can obtain the exclusive default position for a payment slightly above the rival’s $40 maximum bid. Google can also accomplish this payment for exclusivity by offering a sufficiently high revenue share.

In this way, the exclusivity allows Google to maintain its $10 monopoly PPC rather than being forced to reduce the PPC to the more competitive level of $6.67. The $40 total revenue-sharing payment to the distributor amounts to about $2 per click, that is, about 20% of the $10 PPC received by Google for each click. At the same time, deterring competition reduces output. Competition would have also increased investment and search efficiency with both Google and the rival having a high CTR. The Google monopoly market has an advertising output of 21 clicks, whereas output would have risen to 24 clicks if the rival had succeeded in achieving greater distribution.

Judge Amit Mehta rejected Google’s rebuttal claims, including claims that the defaults led to sufficient improvements in general search services. He also rejected the justification that Apple and other distributors might partially pass-on the revenue-sharing payments through lower priced or higher quality mobile devices.

Unconditional revenue sharing

Suppose Google did not attempt to obtain exclusive defaults but instead it simply offered search distributors like Apple a revenue share for every search query voluntarily directed to Google Search. In this scenario, the distributors would still earn a payment for exclusion through the revenue share, but now on a query-by-query basis. In the illustrative example, the total payment for all the distributor’s searches of slightly more than $40 amounts to about $2 per click and about 20% of Google’s $10 PPC.

Even if the bidding is query-by-query, it creates a similar impediment to the rival’s attempts to gain search distribution by counterbidding. This counterbidding would fail for the same reasons as when there are exclusive defaults, that is, Google’s incremental value of maintaining monopoly profits will continue to exceed the rival’s value of earning duopoly profits. Thus, competition is deterred and the monopoly is maintained.

Both the anticompetitive outcome and the mechanism of deterring competition in the unconditional revenue-sharing and exclusive default scenarios are essentially the same. The only difference is the mechanism for achieving distributor exclusivity. In the exclusive distribution agreement scenario, the exclusivity is required by the agreement and then is maintained by the distributors’ economic incentives flowing from the revenue-sharing payments. In the unconditional revenue-sharing scenario, exclusivity is induced by the agreement’s economic incentives flowing from the maintenance of the monopoly price and the monopolist’s profit-margin sharing payments. The search distributors continue to receive a bribe for exclusion, but now the bribe is unit-by-unit.

Distributor heterogeneity and differentiated products

In the analysis so far, the search distributors have been assumed to be identical. But if there is distributor heterogeneity or if the rivals’ product is differentiated, the rival might be able to offer a sufficiently high payment to obtain some search queries. The competitive issue is whether the rival can achieve sufficient sales to achieve and expand beyond minimum viable scale, given the impediments it faces from Google’s conduct and the downward pressure on profits from competition.

The exclusive defaults are all-or-nothing contracts covering all of the distributor’s potential sales. Even if the rival’s differentiated product would be more profitable for some consumers or some types of searches, the distributor may not carve-out those sales. By contrast, when there is no exclusivity and the search distributor can choose which product to sell to particular customers, as in the unconditional revenue-sharing scenario, the rival might be able to obtain some sales from various distributors. Thus, the unconditional revenue-sharing may be less exclusionary than the exclusive dealing contracts because they are unit-by-unit. However, they are still inherently exclusionary and can lead to monopoly maintenance.

This analysis also explains that if Google has exclusive defaults with some distributors, offering unconditional payments to others makes it more difficult for the rival to achieve minimum viable scale by obtaining sufficient sales from the remaining distributors. In this case, the unconditional revenue sharing has exacerbating exclusionary effects.

Possible objections

Because search distributors’ conduct is voluntary, critics might argue that the monopoly equilibrium is highly unstable. Distributors might choose to forgo Google’s higher payments in order to induce competition over time that ultimately will lead to greater distributor profits. However, a distributor likely will be deterred from taking the risk unless it expects a sufficiently high probability of viable entry or fringe expansion, which will depend on enough others doing the same. In this “expectations equilibrium” scenario, distributors coordinating and acting collectively might choose to do so. However, absent such coordination as discussed here, each individual distributor typically would have the incentive to “free ride” by taking the higher revenue-sharing payment from Google while hoping that others act in more prosocial ways.

Critics might argue that this approach to uncommitted payments is over-inclusive because competition is inherently procompetitive, and the payments amount to “competition for distribution.” But this characterization misses the point. When offered by a monopolist, the payments are bribes for exclusion intended to reduce product market competition. These bribes are not inherently passed on to consumers in the output market, particularly when the monopolist sets the price of output.

Exclusive dealing can create distributor loyalty. However, loyalty is not inherently efficient. As a general matter, distributor loyalty can give distributors incentives to provide procompetitive services. But distributor loyalty alternatively can lead to anticompetitive entry deterrence and maintenance of the monopoly retail price.

This analysis also responds to a potential criticism that prohibiting such voluntary payments would condemn common inducements such as retailer slotting fees. That concern also is unfounded. Unlike the hypotheticals here, slotting fees typically occur where there is both manufacturer and retailer competition. However, to join issue with this objection, suppose that a monopoly manufacturer uses resale price maintenance (RPM) to set the monopoly retail price and offers high slotting fees to retailers for the purpose and effect of deterring carriage of a rival new product. If the retailer has limited shelf space for this product category, giving more space to the monopolist manufacturer means less or not space for the entrant and thus a lower likelihood of successful entry. While the retailer’s space allocation decision is voluntary, the slotting fee payment drives the decision to exclude entry.

Taking this a step further, this analysis also explains how RPM can have significant exclusionary effects by raising rivals’ costs of distribution, as recognized in Leegin and analyzed by Asker & Bar-Isaac. RPM can also exacerbate the anticompetitive effects of exclusive dealing. In this regard, Microsoft referred to the critical level of exclusivity for monopolization as sometimes being less than 40-50%. This analysis suggests that the critical level should be lowered still more when the monopolist also employs RPM.

Finally, one might argue that the possible consumer benefits from distributors partially passing on the revenue-sharing payments in the form of lower prices or higher quality other products (such as browsers, operating systems or mobile devices) should be counted. Such out-of-market benefits are generally not treated as cognizable benefits. It is difficult to measure and balance the conflicting effects, which might accrue to different consumers. Counting such benefits also would require determination, measurement and balancing of the benefits, as well as any offsetting harms in other markets. The complexity of antitrust litigation—which is already very complicated—might then become even more unwieldy.

Conclusions

It will not be a surprise if it is suggested in the Google case that the remedy should allow Google to make unconditional search revenue-sharing payments to induce distributors like Apple to voluntarily allocate search queries. This article has explained why permitting such unconditional revenue-sharing would likely fail to lead to effective competition and so should not be permitted.

Even if Judge Mehta were to decide that it would not have been anticompetitive if Google historically had restricted itself to unconditional revenue-sharing in the past decade, that conduct is not what Google did. And so having maintained its monopoly through anticompetitive exclusionary conduct, the goal of the remedy is to establish effective competition going forward by jump-starting competition in the market, even if that means prohibiting some conduct that otherwise might have been permissible in the past.

If the court for some reason feels the need to permit unconditional revenue-sharing, then it would need to offset this permissiveness by strengthening other remedial provisions. These might include greater mandatory data sharing, prohibiting defaults for a longer period of time, reducing the number of permitted defaults (including on Google’s own apps), and divesting Android.

Author Disclosure: Steve Salop is Professor of Economics and Law Emeritus, Georgetown University Law Center and Senior Consultant, Charles River Associates. He consulted with Epic in its cases against Apple and Google.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.