Benjamin Egerod explores the information gap that prevents a majority of firms from lobbying. He argues that the lack of lobbying participation from a majority of firms creates a lopsided playing field that gives more power to those that do.

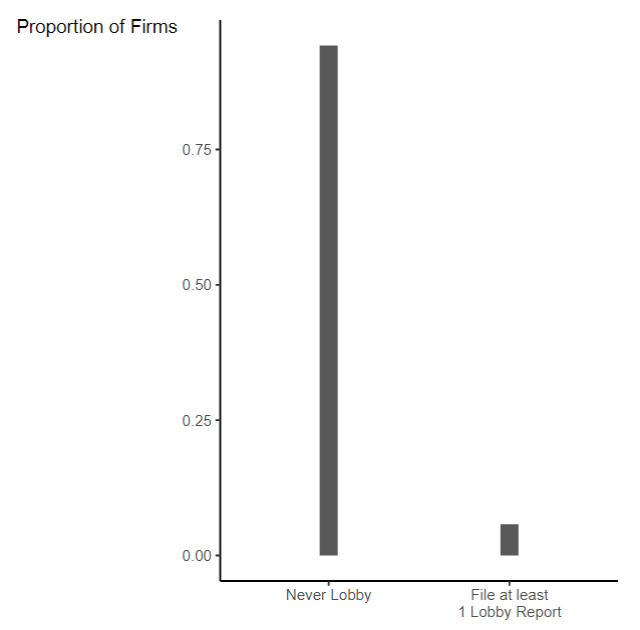

The influence that firms wield on public policy through their lobbying activities attracts significant media attention, and existing research documents that lobbying can improve firm outcomes quite markedly. Among other things, lobbying increases profits and decreases effective tax rates. Yet, the vast majority of publicly traded firms in the United States—around 90%—never file a lobbying report, as can be seen from the figure below. In other words, about 90% of public firms don’t engage in lobbying activity.

Figure 1: Most Firms Never Lobby. Note: The figure shows the proportion of firms that a) file at least one LDA report and b) that never file any report in the period 2000-2020.

This runs counter to the dominant narrative about the political power of business. If lobbying is so beneficial, why do so many firms stay on the sidelines?

In a recent working paper, Lasse Aaskoven and I argue that the fact that firms tend not to invest in lobbying reflects a deeper issue in the market for lobbying services: a widespread lack of information pertaining to the logistics of lobbying. In this article, I’ll explore why many firms that could benefit from lobbying choose not to participate and discuss how information frictions shape corporate political behavior.

Avoiding Risky Investments

Many companies simply don’t know how to navigate the complex and opaque market for lobbying services. Many firm managers prefer to focus on their business and are only tangentially aware that lobbying is even a possibility. If they are aware, the policy-making process is highly unpredictable, making it extremely difficult to estimate the returns to an investment in lobbying. Asking lobbyists will not do much good, as they are incentivized to exaggerate their impact. This implies that the uncertainty surrounding lobbying outcomes deters firms from investing time and resources into political advocacy— even when the potential returns to lobbying are high. This phenomenon mirrors what we know from basic corporate finance: when returns are uncertain, firms tend to either avoid risky investments or require larger expected returns before venturing into them.

In our research, we document this by showing two patterns: First, firms rely heavily on default behavior: If they never lobbied before, no political shock, such as the introduction of tariffs on the firm’s input goods, will make them start. Second, learning about the lobbying practices in other firms will induce a firm to begin engaging in lobbying.

Political Shocks Don’t Push Firms into Lobbying

A large academic literature shows that firms use lobbying to resolve political risks arising either from policies that negatively impact the firm, or from the regulatory setup being unclear. The information extracted through lobbying can allow them to resolve the uncertainty by gaining clarity of the rules and adapting their strategy to prevailing circumstances. Sometimes they may even ward off regulation that would affect them badly. Based on this, we would expect firms to lobby to mitigate the uncertainty imposed by a political shock. However, if firm managers either don’t think of lobbying as a possibility or lack the capability to estimate whether it would be profitable for them to lobby, we wouldn’t expect them to start lobbying in response to shocks of a political nature.

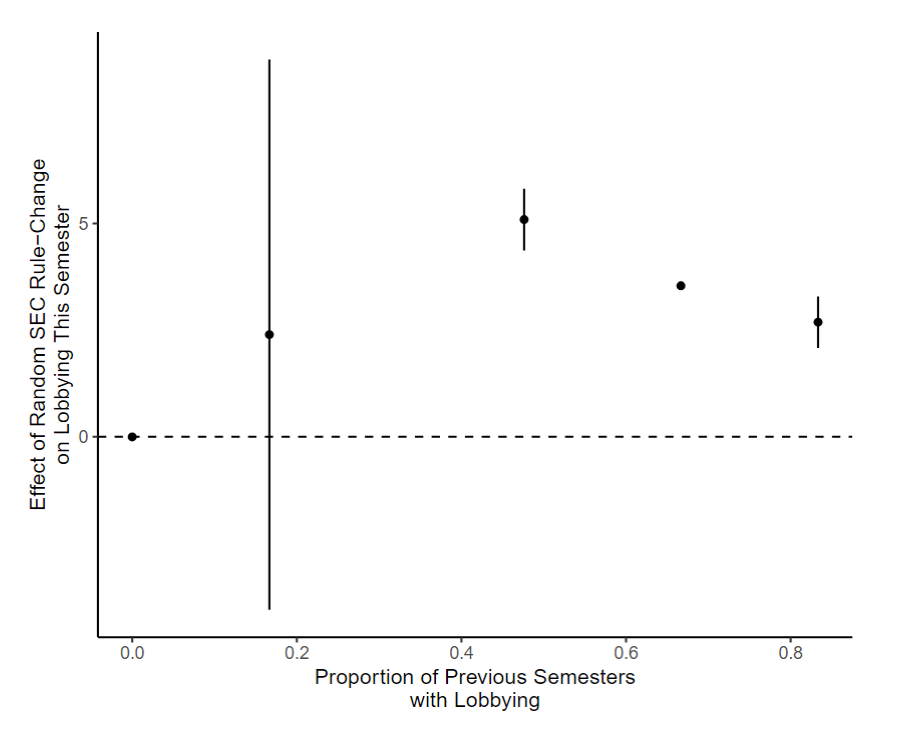

To show that this is the case, we followed recent work by Mary Kroeger and Maria Silfa and used a natural experiment involving a 2004 pilot program by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). This program randomly selected one-third of Russell 3000 and suspended them from the restrictions against short selling that existed at the time. This intervention provides a unique opportunity to observe the effect of a political shock on the behavior of firms. In Figure 2 we show the effect of the intervention on firm lobbying expenditure on the vertical axis and how it differs depending on previous lobbying activity on the horizontal axis. As we can see, there is no effect among firms that have never lobbied before. Further, it is very precisely estimated, as the confidence interval is very narrow around the point estimate. The effect on lobbying is fully concentrated among firms that did previously lobby.

Figure 2: How the Effect of the SEC Experiment Varies with Prior Lobbying.

Note: The figure shows the impact of the SEC’s announcement for different levels of prior lobbying activity. Robust confidence intervals are 95% with firm-level clustering. Bins are chosen to reflect the 25th, 50th and 75th percentile among firms that do lobby. A fifth bin is added for firms with no prior lobbying activity.

This result is remarkably consistent across different types of political shocks. We conducted an additional analysis, where we used a measure recently developed by Tarek Hassan, Stephan Hollander, Laurence van Lent, and Ahmed Tahoun (2019) that relies on transcripts of quarterly earnings calls of publicly traded corporations to measure when the firm’s management is more concerned about political risks. The results mirror the ones presented in Figure 2 almost exactly. Similarly, William Kerr, William Lincoln, and Prachi Mishra (2014) examined the impact of the 2004 decline in the limit of H-1B visas and found that it caused firms already lobbying to increase their activity, but that there was no effect on firms that didn’t lobby previously.

Information Pushes Firms into Lobbying

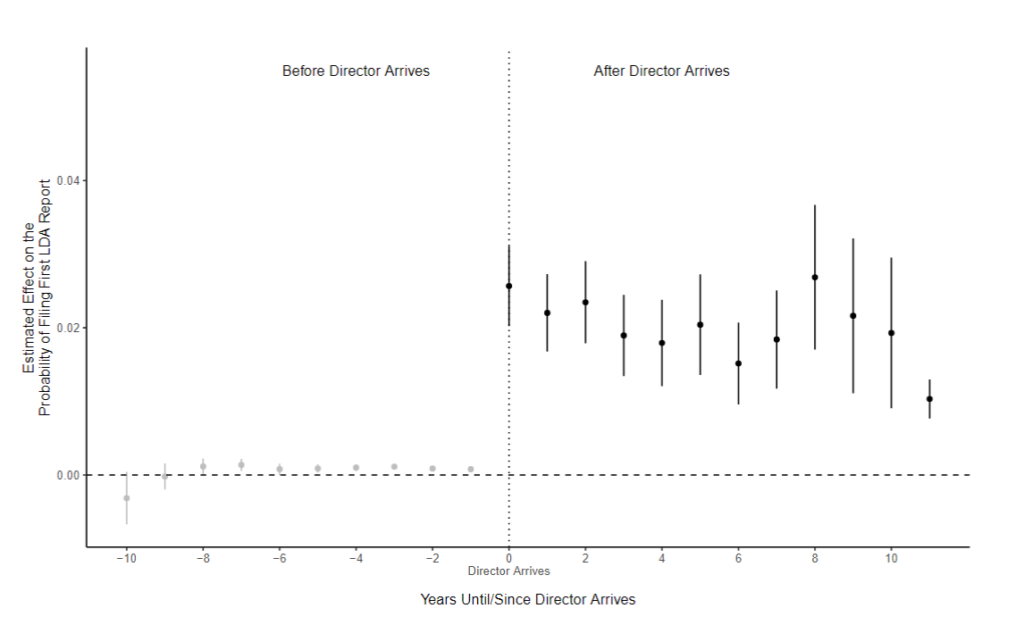

The argument that we advance is that it is the lack of information that keeps firms out of lobbying. Therefore, we would expect firms to start lobbying when they gain access to information about the lobbying activities of other firms. To get at this, we examined the behavior of companies that appointed new directors with prior experience in firms that actively lobbied. When these directors joined the board, the likelihood that the firm would begin lobbying increased significantly.

To illustrate this, Figure 3 shows how firms that appoint a lobbying-director change their probability of lobbying compared to firms that do not make such an appointment. As we can see, when the director arrives, the appointing firm increases its probability of lobbying quite markedly compared to firms that do not make an appointment.

Figure 3: Directors with Information on Lobbying Move Firms Into Lobbying

Note: The graph shows the impact of the appointment of a director that served on a board of a firm that does lobby on the likelihood that the new firm starts lobbying. The sample consists of firms with no previous lobbying activity, the dependent variable is the filing of the firm’s first LDA report. Estimates for years relative to the arrival of the new director.

This pattern held even when the director was appointed under unexpected circumstances, such as replacing a board member who had passed away. Finally, we found that this information effect is present even in firms that rely on trade associations for their lobbying needs. Trade associations typically handle political advocacy on behalf of their members, which might reduce the need for individual firms to lobby. Yet, even in these cases, the arrival of a new director with lobbying experience still increased the firm’s likelihood of lobbying independently. This underscores the importance of firm-specific information in shaping political strategies.

The Democratic Consequences

The fact that most firms do not lobby has significant implications for both individual companies and the political system as a whole. For firms, lobbying can provide a competitive edge, especially in highly regulated industries where policy decisions can have profound effects on the bottom line. Firms that do not engage in lobbying, either due to lack of information or uncertainty about the returns, may be missing out on substantial benefits.

The broader implications for policymakers and the political system are even more concerning. Lobbying serves as a critical source of information for legislators and regulators, helping them understand the needs and concerns of different industries. When only a small subset of firms lobby, this limits the diversity of input available to policymakers. The result is a political system in which the voices of the few—those firms that do lobby—dominate the conversation. This lack of diversity can lead to policies that disproportionately favor the interests of a select group of politically active firms.

Therefore, our research raises important questions about the democratic implications of unequal lobbying. Many participants in the public debate are concerned that any firm is engaged in lobbying. However, our results could suggest that the unequal distribution of lobbying expenditures is the real problem: a small number of firms account for the vast majority of spending, while policymakers never hear from the vast majority.

The barriers to entry in the lobbying market—particularly the lack of information—contribute to this inequality. If more firms had access to information about the benefits of lobbying, it’s likely that a broader range of companies would engage in political advocacy. This could help to level the playing field and ensure that policymakers hear from a more diverse set of voices when making decisions that affect the economy.

Author Disclosure: the author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.