New research from Christopher Stewart, John Kepler, and Charles McClure shows that thousands of large mergers and acquisitions bypass antitrust review because current regulatory thresholds ignore intangible assets like intellectual property and customer data. These unreported deals, particularly in tech and pharma sectors, show signs of being more anticompetitive – with higher premiums paid, increased market power for acquirers, and evidence of “killer acquisitions” in pharmaceuticals.

Growing academic evidence of a rise in corporate market power has captured the attention of policymakers in the United States, leading to a wave of recent policy actions calling on antitrust regulators to scrutinize mergers and acquisitions (M&A) that consolidate product markets. Such consolidation, it is argued, increases market power, leading to higher prices, fewer choices, and reduced quality for consumers. A necessary condition for enforcing these policies is that regulators become aware of potentially harmful mergers in the first place. In a new paper John Kepler and Charles McClure, and I show that thousands of large M&A are never seen by regulators solely because the criteria that determine regulatory review overlook an increasingly important asset in the economy: namely intangible capital.

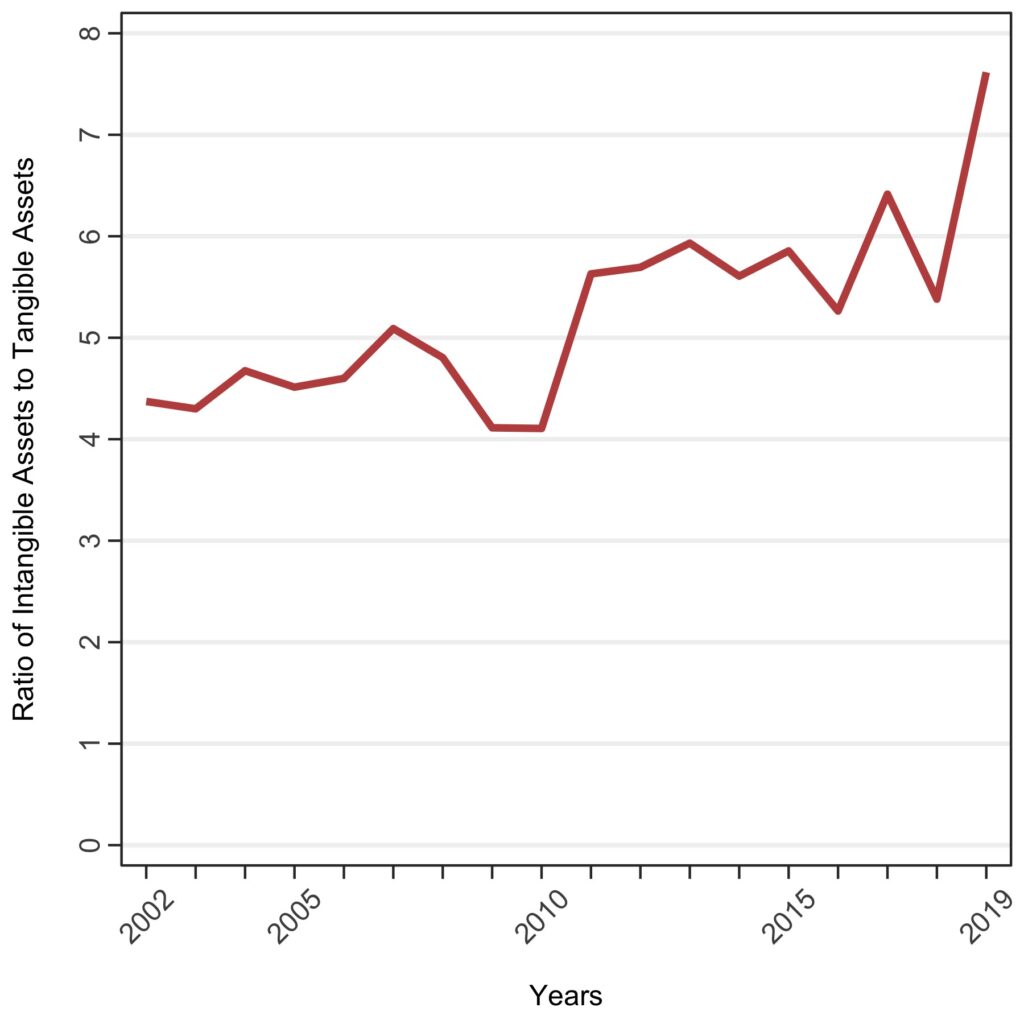

Why is intangible capital systematically overlooked by antitrust regulators? For deals above a certain deal-value threshold, regulators–i.e., the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ)–use the size of the target firm’s assets to determine which M&A must be reported. However, these asset-size thresholds only consider the value of assets from balance sheets reported under U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), which exclude nearly all self-generated intangible assets, such as intellectual property and customer data. This exclusion suggests that regulators ignore an increasingly important asset in the economy, despite recent efforts by the FTC and DOJ to explicitly focus on high-intangible industries like pharmaceuticals and technology. Indeed, as the figure below shows, the amount of acquired intangibles is now eight times the amount of acquired tangible assets.

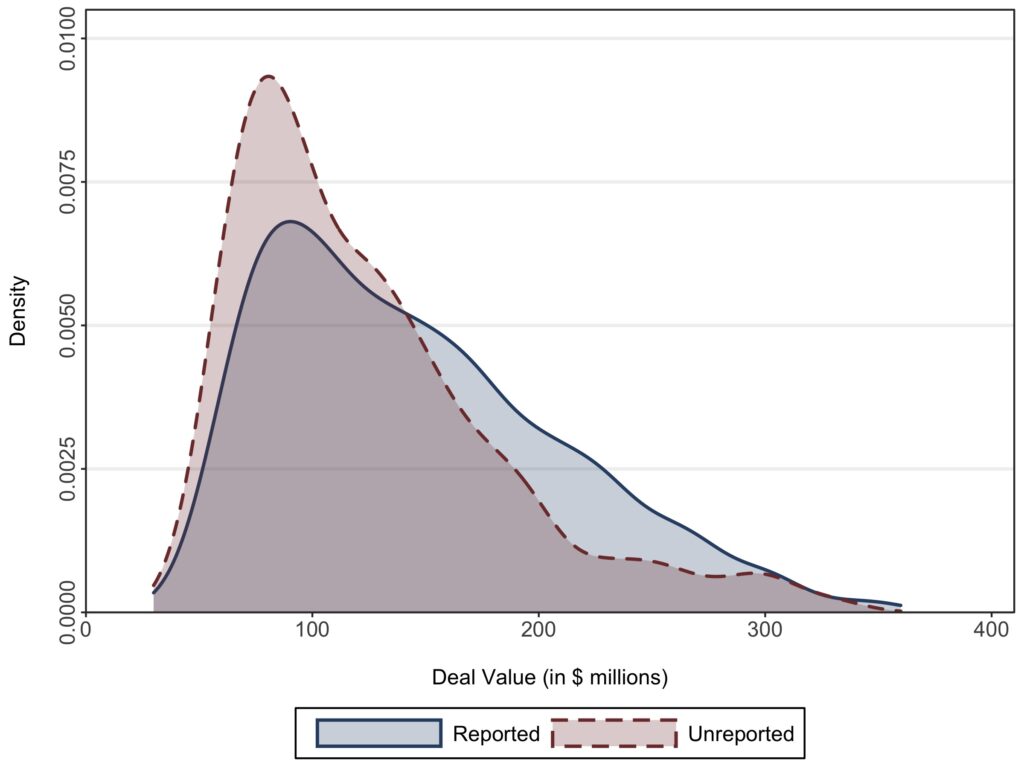

We find that the use of asset-size thresholds results in thousands of deals–particularly in the technology and pharmaceutical sectors–never being reported to the FTC and DOJ, despite these deals having nearly identical transaction values to those that are reported, as shown in the figure below. If regulators required firms to add intangible capital to the targets’ assets, we estimate that the number of deals reported to the FTC and DOJ would increase by approximately 263 per year, more than half of which are horizontal consolidations among competitors.

Do unreported deals lessen competition and, as a result, harm consumers? If unreported deals provide anticompetitive benefits, we conjecture that acquirers should pay a higher premium. Supporting this idea, we find unreported acquisitions have a 12% higher premium than reported deals. In fact, this higher premium is entirely driven by deals that consolidate product markets—precisely where anticompetitive behavior is most likely to emerge. Moreover, if these deals reduce competition, investors may view this as beneficial for the acquirer and its remaining competitors, notwithstanding the evidence of higher premiums. Consistent with this, we find a 5.6% increase in the equity values of acquirers following the deal announcement, and a 0.7% increase for rivals, in unreported deals.

A plausible channel through which unreported deals could benefit shareholders, at the expense of other stakeholders such as consumers, is by allowing acquirers to charge prices well above their costs–i.e., higher markups. Consistent with this idea, we find that acquirers whose deals bypass merger review have higher markups relative to reported deals, and these markups persist for at least two years following the merger. Furthermore, this effect is concentrated in acquisitions involving firms with product-market overlap and when acquisitions of intangible assets can have an immediate impact on prices, such as the consolidation of developed technologies and brands.

Our preceding evidence suggests that the acquisition of intangible assets allow firms to both bypass antitrust scrutiny and provide anticompetitive benefits. One potential explanation for the anticompetitive benefits we document is that the acquired technologies in unreported deals are of higher quality. To examine this, we focus on over 9,000 patents transferred across reported and unreported deals and find that acquired patents in unreported deals are indeed of higher quality, as measured by their importance and the likelihood to be breakthrough technologies.

Another way in which anticompetitive benefits could arise in unreported deals is through the acquisition of undeveloped products. Unreported deals could, for example, allow acquirers to buy and discontinue early-stage projects, with the goal to preempt future competition–i.e., what Colleen Cunningham, Florian Ederer, and Song Ma call “killer acquisitions.” To examine whether bypassing antitrust review allows acquirers to buy and discontinue future competition, we focus on the pharmaceutical industry, which has historically received particular attention by the FTC and DOJ. Using data on the types of drugs under development, we find that unreported deals are more likely to involve targets and acquirers with new drug projects that directly overlap, and that these overlapping drug projects are 40% more likely to be discontinued following acquisition. Importantly, this result does not appear to be driven by differences in the ability to develop drug projects, as acquirers in unreported and reported deals have similar discontinuation rates outside of these acquired projects.

We also find that this pattern of buying and discontinuing drug projects has broader economic effects. For example, in additional tests, we find that entrepreneurs seem to react to these preemptive acquisitions by initiating “copycat” drug projects, in the years immediately after these deals, rather than pursuing truly novel therapeutic treatments. This evidence is consistent with the economic incentives of higher deal premiums we have documented. It is also consistent with our finding that the sellers of target firms in unreported deals are more likely to be sophisticated investors, such as venture capital firms, who one might expect to both be aware of the antitrust screening criteria and have the incentives to sell their firms before they exceed these asset-size thresholds.

Collectively, our evidence suggests that unreported deals are more likely to be anticompetitive. However, it may still be the case that competition regulators are not concerned about deals of this size. Our evidence suggests otherwise: roughly 25% of all Second Requests–the most stringent form of antitrust scrutiny by the FTC and DOJ short of litigation–occur in reported deals of similar size. While the deals are rarely blocked, deals of this size are clearly of interest to regulators, but are overlooked solely because of the accounting treatment of intangible assets.

This begs one final question: if antitrust regulators are not aware of these deals, why doesn’t private litigation substitute for public enforcement? We investigate and do find some evidence that private enforcement substitutes for a lack of public oversight, albeit imperfectly, on account of various legal frictions we discuss in the paper. Given that the U.S. relies on both public and private enforcement, the presence of such frictions suggests many anticompetitive deals are likely to continue, unhindered by public or private enforcement.

Bio: Christopher Stewart is an assistant professor of accounting and Fama Faculty Fellow at University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business. His research, which lies at the intersection of accounting, corporate finance, and industrial organization, is primarily concerned with addressing questions that broaden our understanding of how accounting information, corporate disclosure, and transparency shapes product market competition.

Author Disclosure: the author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.