Lulu Wang writes that the Department of Justice’s lawsuit against Visa for maintaining a monopoly in the debit card market will, if victorious, only impact a fraction of the transaction fees that burden merchants. And if the lawsuit opens up the market to more competition, there are reasons to believe a more fractured card network could end up hurting consumers and merchants.

The Department of Justice’s (DOJ) lawsuit against Visa alleges the company has monopolized the market for debit card network services. The case raises critical questions about how to regulate competition in industries with network effects, wherein scale and higher market share improve the quality and price of services. However, even if the government prevails, the resulting increase in competition is unlikely to bring large benefits for merchants or consumers.

The Price of a Payment

Consumer payments in the United States are overwhelmingly card-based, concentrated among a few network providers, and costly for merchants. The market is split between four major competitors: Visa (with ~61% of the card market based on transaction value), Mastercard (~25%), American Express (~11%), and Discover (~2%). Visa holds around 60% of the debit card market. In 2023, merchants paid $172 billion to process about $11 trillion in credit and debit card transactions.

The DOJ’s monopolization suit against Visa is part of a sequence of antitrust cases that have sought to bring down the cost of payments by reducing market concentration. For example, in 2021 the DOJ sued to stop Visa’s acquisition of nascent payment platform Plaid. The DOJ argued that the merger would suppress competition that would otherwise bring down the cost of processing online debit transactions for merchants. Visa and Plaid ultimately abandoned the merger. The DOJ is currently reviewing the proposed merger between Capital One and Discover, which would create the largest credit-card issuer in the U.S.

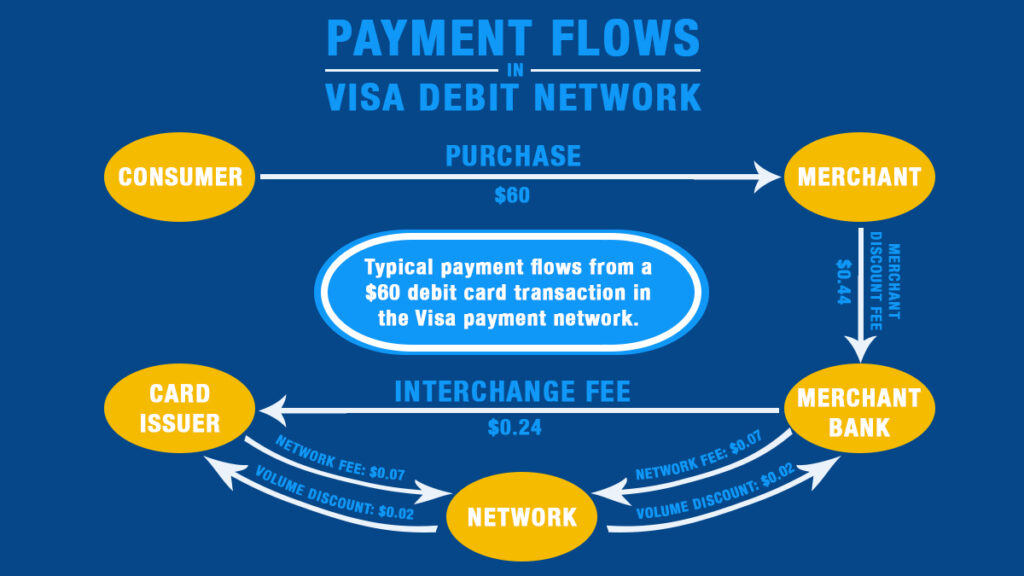

To understand how the most recent lawsuit differs from previous cases, it is important to understand how the costs of payment acceptance are shared by different market participants.

A typical Visa debit card transaction is for $60 and costs the merchant around 44 cents in fees. These fees are paid to the merchant’s bank, called the “acquirer.” While a portion of this amount is kept by the acquirer, the majority—around 24 cents—is passed on to the card issuer, such as Chase, Bank of America, or Capital One, in the form of interchange fees. These fees fund essential banking services like checking accounts. Visa specifically then collects network fees of about 14 cents per transaction from the issuers and acquirers, although four cents are typically returned to these parties in the form of volume discounts. The process is similar for Mastercard debit card payments. Discover and American Express observe a different process because they are both the issuer and the acquirer.

The DOJ’s Allegations

The DOJ contends that Visa maintains its dominance through two main strategies. First, Visa offers significant volume discounts to large issuers and acquirers, incentivizing them to route transactions through Visa’s network instead of competing debit networks. In effect, these discounts lock major banks into Visa’s network, depriving smaller networks of the scale they need to compete.

Second, the lawsuit argues that Visa pays potential competitors to not compete. Apple, for instance, could have developed its own proprietary payment network but instead chose to make Apple Pay an on-ramp for Visa’s system. For this, Apple receives approximately half a cent per debit transaction and 14 cents per credit transaction—small sums that nonetheless add up to hundreds of millions annually.

The DOJ argues that Visa’s conduct leads to higher network fees by removing a potential competitor. This makes the lawsuit unique, as the DOJ is not challenging the interchange fee, paid to the card issuers, which has been the focus in past lawsuits. Instead, the focus is on the 14-cent network fee and the four-cent volume discounts.

The Central Question of the Case

The key challenge for the DOJ is to prove that these volume discounts and incentive payments are anticompetitive attempts to deter entry, rather than procompetitive investments in the quality of the network.

Volume discounts can compensate large banks for their outsize role in promoting payment adoption. For example, when Chase advertises contactless payments on the NYC subway, it encourages broader consumer adoption of Visa cards issued by other banks.

Visa’s payments to Apple can also be seen as a way to compensate Apple for their costly investments in Apple Pay. Because Apple earns a fee on every transaction processed through Apple Pay, it has strong incentives to invest in a high-quality app. These investments have paid off. According to the Pulse 2021 Debit Issuer Report, Apple Pay adoption by debit card users is more than 10 times higher than the adoption of Google Pay. Visa’s incentive payments could be seen as fostering complementary investments, rather than deterring competition.

At its core, the DOJ’s case rests on the idea that payment markets feature strong network effects. Yet in such industries, incentive payments often serve a critical purpose to coordinate investments. Why would Apple invest heavily in promoting payment technology if much of the benefit accrues to other players in the system? Visa, as a central player, can drive the adoption of new technologies, which in turn benefits consumers, merchants, and issuers alike.

Network Fees are a Small Part of Merchants’ Expenses

Even if the DOJ’s case is successful, the immediate relief for consumers and merchants will likely be small. Visa’s network fees, while significant in aggregate, account for only a fraction of the total cost merchants face when processing a debit card transaction. For instance, out of a 44-cent processing fee, only about 10 cents is tied to Visa’s network charges, while the bulk is driven by interchange fees and acquirer costs. Therefore, of the $31 billion in annual debit card fees that merchants pay, network fees only account for around $7 billion. Moreover, this lawsuit does not address credit card fees, which total around $130 billion per year.

The Dark Side of Network Competition for Merchants

Of course, in the longer term, a DOJ victory may encourage the entry of new fintech debit networks. However, this can have the perverse consequence of actually increasing merchants’ costs of payments and hurting consumers by encouraging the proliferation of inefficient payment networks.

Payment markets are a classic example of two-sided markets: networks must attract both consumers and merchants to succeed.

As I show in my paper “Regulating Competing Payment Networks,” competition in payment markets can lead networks to offer better rewards without reducing merchant fees. This happens because consumers are highly sensitive to rewards like cash back and points, while merchants, fearing the loss of customers, are often willing to absorb higher processing fees. Competition thus accelerates the adoption of high-fee, high-reward payment methods like premium credit cards.

Opening the market for debit could create opportunities for fintech companies to develop new high fee, high reward payment methods by exploiting regulatory loopholes.

American Express’ and Discover’s debit card strategies illustrate this regulatory arbitrage. The Durbin Amendment, passed in 2010 as part of the Dodd–Frank financial reform, caps interchange fees only for Visa and Mastercard debit cards (at about 0.42%). But because American Express and Discover are both merchants and acquirers, they do not make interchange payments between other banks, and thus their debit cards are exempt from the Durbin Amendment. This exemption is valuable. American Express and Discover can charge merchants higher debit card fees than Visa and Mastercard, and thus are the only two large providers of no-fee, rewards debit cards on the market. This exemption is part of the reason why Capital One is trying to merge with Discover. By shifting all of its customers’ debit cards from Mastercard to Discover, Capital One will be able to earn higher interchange fees on its customers’ debit card transactions (the average Discover debit fee is 1.41%, as is that for American Express).

Of course, if new entrants can introduce higher quality or lower cost payment products, that could make consumers better off. But that is not the only route to riches for new entrants. Even inefficient entrants could gain substantial market share not through “competition on the merits,” but rather by exploiting a regulatory advantage over the incumbents. If merchants pass on higher fees into retail prices, consumers can ultimately pay the price of this intensified competition.

Conclusion

The DOJ must prove that Visa’s payments to Apple and large banks are anticompetitive rather than legitimate investments in network quality and growth. However, even if the lawsuit succeeds, it is unlikely to deliver the desired reduction in fees. Competition instead may further inflate merchant fees that fund more generous consumer rewards.

Author Disclosure: the author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.