Thomas Malthouse explores the skewed financial models that lead American railroads to underinvest in maintenance and profitable expansion, producing delays, derailments, and environmental catastrophes such as those that occurred in East Palestine, Ohio, in 2023.

American freight railroads have suffered an unwelcome prominence in recent years. The 2023 East Palestine, Ohio derailment forced the evacuation of the town due to a large-scale release of hazardous chemicals into the air and water—an incident caused in part by inadequate maintenance on railcars. Last fall, rail unions threatened to strike over lack of sick days, overwork, and what they argued were excessively punitive disciplinary policies—a strike that would have shut down the production and transport of essential industrial commodities and thrown the recovering American economy into recession had Congress and the Biden administration not intervened to force a settlement. After laying off 20,000 workers and mothballing equipment early in the Covid-19 pandemic, operational issues and labor shortages at the freight railroads worsened and prolonged supply chain issues as containers piled up at West Coast ports waiting for transportation to inland terminals and distribution centers.

Most American railroads are publicly traded corporations. They are listed on stock exchanges, are governed by a board of directors elected by shareholders, and are free to set shipping rates and direct capital investments without state direction. The infrastructure is fully owned and maintained by these companies and—excepting one-off agreements—for the exclusive use of the owner. For example, the shortest and fastest route between Chicago and Kansas City is owned by Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF). If I, as a shipper, would like to send goods between these cities, I can either accept the service offered by BNSF (with little room to negotiate price or service quality), use the services of the other rail carrier on this route (Union Pacific), a far slower and less direct alternative route, or ship by truck. Very few markets are served by more than two carriers, and many are monopolies, with trucking providing the only source of competition for some goods (bulk commodities like coal can only be transferred by railroad).

Although railroads are public companies with shareholders, institutional dynamics mean they do not behave as profit-maximizers, and this has been a significant source of their ongoing problems. Railroad transport is viewed by analysts as a commodity, lacking differentiation from one company to the next. This is why, for most of the past century, the primary metric used by investors to compare railroads is to quantify their efficiency using the operating ratio—the share of operating revenue spent running the railroad (encompassing labor, fuel, maintenance, depreciation, and so on). A lower operating ratio indicates a more efficient railroad, with more ability to issue dividends or buy back stock. Executives have long sought to lower their operating ratio and regularly brag about doing so in their annual reports.Activist shareholders increasingly push for aggressive programs to minimize operating ratios.

The problem is that the operating ratio is an extremely flawed measure. An overemphasis on this metric will cause railroads to focus on the most profitable traffic—generally bulk commodities and long-distance container traffic—ceding time-sensitive and short-haul freight to trucking, even when it could be profitably transported by rail. Maintenance and capital costs are included in the operating ratio, pushing railroads to underinvest in their physical plant—lowering the speed and reliability of the rail network, and increasing the risk of derailments. Incidentally, this is a major cause of Amtrak’s dismal service outside the Northeast (where Amtrak owns its own railroads instead of renting them from freight railroads): freight railroads are legally required to prioritize passenger traffic, but outdated and underbuilt infrastructure mean Amtrak’s services will incur huge delays even if the freight carriers are attempting to meet their obligations in good faith.

For a concrete example of this dynamic, consider the Powder River Basin line. Wyoming’s Powder River Basin contains enormous deposits of low-sulfur coal, demand for which skyrocketed after the passage of the Clean Air Act in 1970. At this point, rail infrastructure in the area was essentially nonexistent and the western railroads were facing severe financial difficulties. The Burlington Northern Railway (then one of the major railroads in the west) proposed the construction of 126 miles of railroad to access these deposits, the first new mainline railroad to be constructed since 1931. This investment, funded by $32.5M in newly issued bonds, faced significant resistance from a faction of shareholders and management who doubted the long-term viability of the project and were generally skeptical of large capital investments. The line was enormously successful, returning the western railroads to profitability even as the eastern lines continued to struggle. Although demand for coal has dropped significantly in recent years, the Powder River Basin lines remain the most heavily trafficked in the country. Even so, the general skepticism of capital investment among rail management and shareholders remains, and there has been little interest in identifying similarly profitable investments that would open new markets or lower operating costs.

Instead of investing in profitable railroad market expansion, the dominant strategy railroad management has used to improve operating ratios in recent decades has been precision-scheduled railroading (PSR). PSR holds that railroads should stretch existing assets as much as possible to maximize operating efficiency, using crews and equipment more intensely, spinning off non-core business to smaller railroads or trucking, and aggressively scheduling trains to avoid delays due to congestion. These are—in principle—well-founded ideas and are standard practice on the world’s most efficient rail systems. A 1975 study found that a typical freight car spent 60% of its time waiting in rail yards for connecting trains and only 15% actually moving (the remaining 25% is spent at its origin and destination). By reducing these transfer times and otherwise running a more efficient operation, railroads should be able to improve the quality of service provided while lowering costs.

However, realizing those benefits still requires a program of capital and maintenance investment in which United States railroads have been unwilling to engage. Tightly scheduled trains can reduce the time spent waiting in rail yards or at congested junctions—but that requires trains that won’t break down and infrastructure that doesn’t require rail crews to frequently stop. Infrastructure needs to be adapted for the proposed operating regime, with passing tracks long enough to hold the longest trains and designated stopping points that won’t leave road crossings or passenger trains blocked.

As implemented, PSR has mostly realized operating efficiencies by squeezing labor and pushing the costs associated with poor operations onto the public. Train lengths have continuously increased even as infrastructure remains unchanged, leading to more derailments, delays, and blocked road crossings. Delays—even for the highest-priority trains—are measured in hours or days, leaving crews without regularly scheduled shifts and on-call around the clock—a major driver of the recent labor unrest. Rather than building new terminals and figuring out how to efficiently transfer cargo by rail, the railroads drive hundreds of thousands of trucks between 19th-century rail yards located in dense urban neighborhoods—increasing pollution, congestion, and the risk of injury and death on busy city streets not designed for intense truck use.

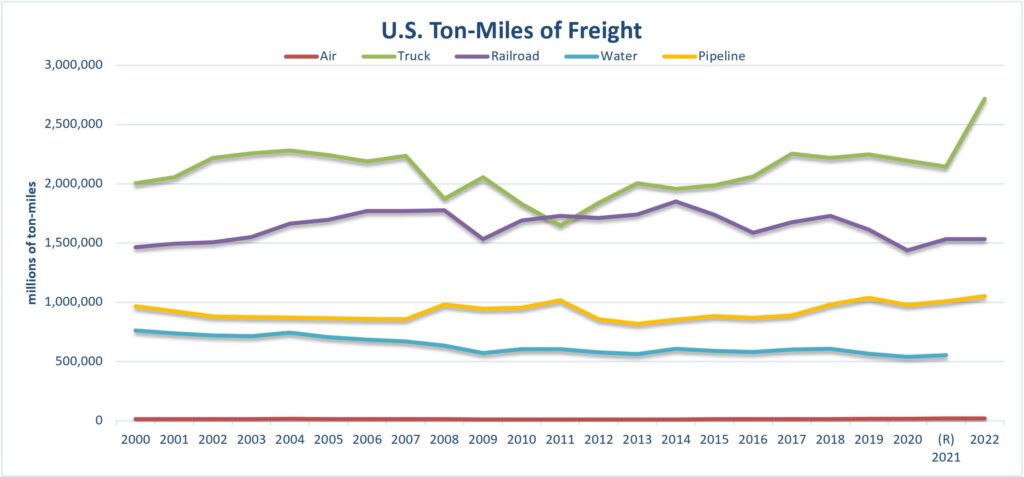

This broken operating regime also hurts firms who depend on rail transportation. After furloughing and laying off 20,000 workers during the pandemic, rail carriers have been regularly suspending service (or “embargoing”) to shippers, particularly smaller firms or those with less ability to negotiate better terms. The inability to maintain a schedule and constant risk of a service failure forces customers to maintain larger-than-optimal stockpiles of input goods, raising costs and pushing traffic to trucking (with all the associated externalities). Surface Transportation Board chairman Martin Oberman noted in a 2021 speech that the share of freight carried by rail in the U.S. has decreased over the last twenty years, even as it has significantly increased in Canada and Europe—a difference he attributes to these operational practices.

Figure 1. Trends in Freight by Method

Although minimizing the operating ratio reliably increases profits without taking on the risk and complexity of a more comprehensive operating and capital strategy, it has led to an industry that is incapable of meeting firms’ and the public’s need for a capable rail sector. In particular, the failure of railroad governance also has serious climate implications. Rail is—compared to other modes of transportation— easy to decarbonize. Overhead electrification is a century-old technology and is a standard feature on high-traffic railways worldwide. An electrified railroad is cheaper to operate, the trains are more reliable, and emissions are reduced or eliminated entirely, depending on the source of electric power. Countries far more capital-constrained than the U.S. have invested heavily in rail electrification in recent decades, recognizing that the operational and environmental benefits result in a healthy return on investment for the rail company. Despite this, American freight railroads have no plans to electrify, as it would have no consequence for the operating ratio. To the extent that concrete plans exist for the decarbonization of the American rail sector, they depend on the development of battery- and hydrogen-powered locomotives. The only existing applications of such trains is in local passenger transportation and low-speed shunting, and adapting them for American long-haul heavy freight services is likely impossible.

Still, this myopic focus on the operating ratio is likely to remain a dominating feature of railroad governance in the short term. In May 2024, Norfolk Southern (the eastern railroad whose train was involved in the East Palestine disaster) narrowly avoided a takeover by activist shareholders by promising to double down on PSR and cutting operating costs further. Although concessions on sick leave and paid time off defused the strike threat last year, the industry remains understaffed and reliant on overtime to keep functioning. The worst of the pandemic-era supply chain crises have passed, but service remains unreliable and many of the routes cut during the pandemic still have not been restored.

To be clear: American railroads do a lot right. They efficiently carry incredible amounts of bulk cargo, without which entire sectors (agriculture, manufacturing, and so on) would cease to exist. Their capital projects have proven largely immune to the cost bloat afflicting public sector highway and transit projects. They provide hundreds of thousands of well-paying union jobs, many in regions without other opportunities. Their role cannot be filled by road, air, or marine transportation, and they will necessarily be a major player in any serious climate or industrial policy.

So what can be done to address these issues of railroad governance? First, shareholders (particularly institutional investors) would do well to note that the current regime of operating ratio-driven austerity is not profit-maximizing, and that relatively small investments in infrastructure and working conditions with an eye towards improving the network’s capacity and reliability can have outsize impacts on traffic growth and profitability. For example, consider BNSF. This company—unlike all the other large railroads—is a privately held subsidiary of the Berkshire Hathaway corporation, and has been more insulated from the most destructive shareholder pressures. It has been more willing to undertake capital projects, particularly those that will increase traffic, and has grown to become the largest American railroad, even as the rest of the sector’s traffic volumes have stagnated or shrunk.

Second, public investments in rail infrastructure should be designed to address coordination failures between rail companies and to reduce the externality burden on the public. Transit analyst Uday Schultz has written at length about what better freight policy would look like, and notes that projects like Chicago’s CREATE should be taken as a model for freight investments in other congested urban regions—comparatively small public investments are pooled with capital from the railroads to eliminate road crossings, facilitate rail-to-rail transfers without intermediate trucking, and allow through freight to avoid congested nodes entirely at a scale that would be impossible without coordination. Such projects are also a prerequisite for expanded regional and intercity passenger rail service. Most public investment up to this point has taken the form of one-off projects—eliminating a single problematic road crossing or allowing passenger trains on a single line, for example—rather than the network-oriented approach Schultz recommends, limiting the impact of that public money.

Finally, investments in rail infrastructure should play a more prominent role in current and future federal climate and infrastructure policy. Rail electrification likely offers an acceptable return on investment for the railroad, lowers the climate impact of railroad operations, and eliminates the public health costs of diesel exhaust in urban areas—but railroads have been reluctant to make such a large capital investment. State and federal departments of transportation would do well to use funds from 2021’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act to fund such electrification, realizing a satisfactory rate of return for the public buyer in addition to these climate and health benefits. Similarly, targeted investments in overloaded or outdated rail lines and junctions would do more to reduce congestion than continuing to expand highways, while also lowering emissions by shifting freight and passenger traffic to the rails. Federal infrastructure funding is flexible by design, but most investment continues (largely, I argue, due to institutional inertia) to be in roadway expansion even when other projects would offer a higher cost-benefit ratio, more effectively reduce congestion, and be more aligned with climate objectives.

The rail network remains a critically important component of American transportation infrastructure, but a legacy of underinvestment and poor governance have left it fragile and underperforming. Railroad investors and stakeholders have significant opportunities to increase their returns through a targeted program of infrastructure investment and operational improvements if they leave behind the austerity-driven governance that characterized the industry for most of the last century. The sector also should be a target for public investment, with rail upgrades and electrification offering a public benefit and return on investment higher than those typically realized by public works projects, in addition to substantial climate and air quality benefits.

Author Disclosure: the author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.