Bank regulators have always assumed that bank deposits are ‘sticky,’ but the advent of digital banking is changing that. New research focuses not on the danger of bank runs, but rather on the new dangers of ‘bank walks.’

From April 2022, when the Fed started increasing interest rates, $860 billion of bank deposits disappeared, most likely moved by individuals into higher-yielding money market funds. Two-thirds of that move occurred before the collapse of SVB. It is a silent walk that cannot be stopped by any deposit insurance and that will undermine the stability of the banking system in the months to come.

After the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), many commentators have pointed fingers at social media, responsible for accelerating the bank run that killed SVB. Less attention has been dedicated to the role mobile banking has played not only in SVB’s bank run but also in the preceding massive exodus of deposits from the banking sector. While this exodus of funds from banks took place more slowly — more akin to a bank walk than a bank run— it is equally, if not more, momentous for the banking system.

To understand the problem we need to start from the regulators’ view of banks. As beautifully illustrated by the interview of Eric Rosengren in the podcast Capitalisn’t, regulators assume that deposits are sticky, meaning that they are not being moved around very often by their owners. If they are indeed sticky, banks can afford to suffer some losses in their held-to-maturity assets, especially if these losses are due to interest rate risk and not to credit risk because at maturity, a Treasury bond will return the promised amount.

Thus, if deposits stick around, the bank can cover them. This is the justification for why held-to-maturity assets are not marked-to-market. Since they are not marked to market, they are not even hedged, because the hedging of an asset marked-to-book would generate very high volatility of earnings, which bank executives hate.

The entire bank regulatory structure is based on the assumption that deposits are sticky. Historically, this assumption was true. But is it still true? If not, what does it mean for the stability of our banking system and the flexibility of our monetary policy?

Unfortunately, there is precious little research on the topic, so we decided to look at the data. The advent of digital banking represents one of the most important structural changes in US banking in recent memory. We proxy for digital banking in general by using data on banks’ mobile applications.

Since the Great Financial Crisis in 2008, over half of the roughly 4,000 existing banks have introduced a mobile app. In many cases, the app is clunky and very few customers use it. In others, it is the main way customers interact with the bank. Fortunately, Koont is able to measure the use of mobile apps by looking at the number of reviews an app receives on either the Apple or Android app store, in her study of the effects of digitalization on the stability of the banking sector.

Digital banking offers customers the possibility of switching deposits without leaving their sofas. It also makes the discovery of the rates offered by alternative investment vehicles easier. Thus, it is reasonable to expect that deposits in banks with a well-functioning mobile app will be less sticky than deposits in banks without such a convenient app. Is that true? Unfortunately, the data on deposit disaggregated by banks is available only until the end of 2022. Yet, there is an advantage in ignoring the recent months: whatever movement happened in 2022 could not be attributed to a bank run. Thus, we really focus just on the digital deposits walk.

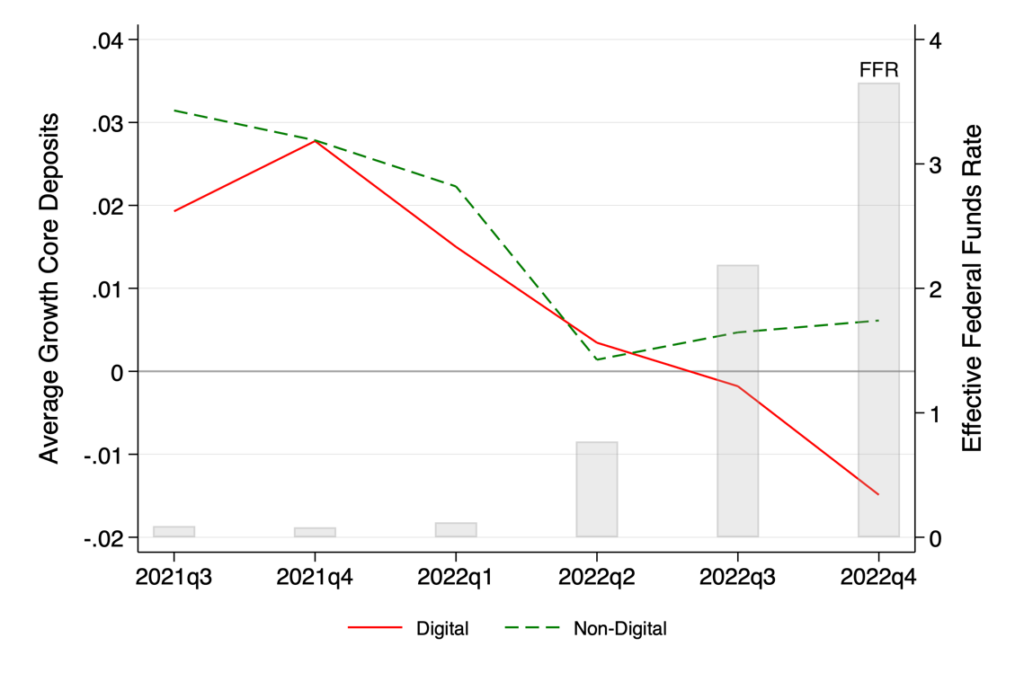

Figure 1 shows the quarterly average growth in core deposits, computed separately for digital and non-digital banks. We restrict the sample to banks between $5 and $250B in assets, as they have been so the focus of the recent news. Digital banks are those that have at least 300 mobile app reviews and that have log(number of reviews)/log(deposits) above the 75th percentile.

The rate of growth of deposits of digital banks diverges sharply in the second quarter of 2022 from that of non-digital banks, which aligns with the timing of an uptick in the pace of fed funds rate increases. In fact, digital banks start experiencing deposit outflows in the third quarter of 2022.

FIGURE 1

Much has been made of the differential behavior of insured versus uninsured deposits. When we restrict our attention to insured deposits, below the guaranteed level of $250,000, the picture looks identical. Whatever is going on with the banking system is not just about the flight of uninsured deposits.

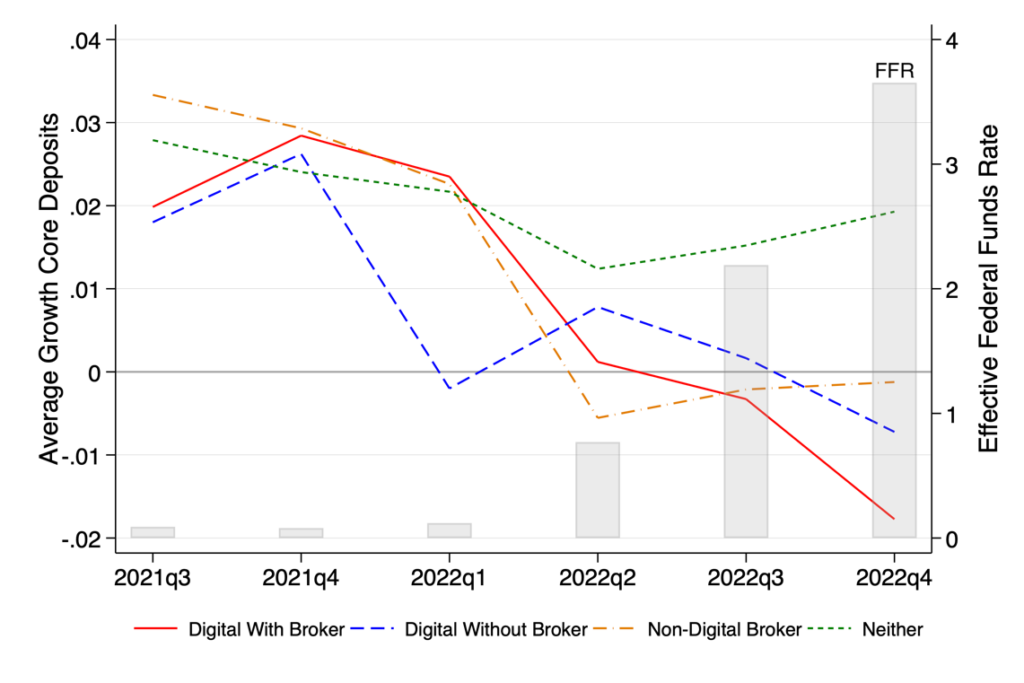

Where are the deposits flowing to? The most likely outlet is money market funds or Treasury bills and bonds directly, where consumers can now get better yields on their cash. If this is the case, banks that own a brokerage may actually facilitate customers’ ability to move out their deposits. As Google likes to repeat, competition for deposits is “a click away.” To explore this, we categorize banks into those that have a brokerage, measured as non-zero income in fees and commissions from securities brokerage in their regulatory Call Reports. We find that 10% of banks report nonzero brokerage income. In Figure 2 we reproduce Figure 1 but now we split the sample into four groups: Digital and non-digital and banks with brokerage fees versus those that don’t report these fees.

FIGURE 2

The difference is very stark. Banks with neither an effective mobile app, nor a brokerage account see their deposits grow at a steady 1.5% rate in the third and fourth quarter of 2022, in spite of the rising interest rates. By contrast, banks that have both a functioning mobile app and a brokerage account see their deposits drop by 2% in the fourth quarter of 2022.

In a forthcoming working paper, we use a panel of bank deposit growth from 2010 to 2022 to measure the elasticity of deposit growth to changes in the federal fund rate. We find that a 400bps increase in the fed funds rate, roughly what the Fed increased rates in 2022, leads to a 9.6% drop differential relative to trend in core deposit growth for non-digital banks that do not report any brokerage fees. The differential drop becomes 15.2% for digital banks reporting brokerage fees.

The fact that a bank has a digital app and/or a brokerage account may correlate with other characteristics that make deposits behave differently. To dispel this possibility in our forthcoming paper we consider deposit flows within-bank-year (that is, we include a bank-year fixed effect), looking at variation across their branch networks. We estimate a bank-county-year panel regression for the universe of banks over the period 2010 through 2022. Specifically, for a given bank, we look at whether deposit flows are more sensitive in counties that have higher internet usage, depending on whether the bank is digital or not. Household internet usage comes from the Census ACS 2019 5Y, defined as the proportion of households in a county that have internet subscriptions. We also include state-year fixed effect so that identification comes only from counties within a given state and, finally, county fixed effects to absorb out time-invariant differences across counties.

We find that banks’ deposit outflows are more pronounced in markets with higher internet usage, but that this is only the case for digital banks, regardless of whether they report brokerage fees or not. County-level deposit outflows are 6% larger, and rate increases are 20% larger for a given digital bank that reports brokerage fees in counties with 100% household internet usage when compared to counties with no internet usage whatsoever.

It is clear that deposits have become much less sticky, especially in banks with well-functioning mobile apps and a brokerage, like Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic Bank. This is not a problem if these banks do not have large losses in their held-to-maturity assets or in their loan portfolio. If they do, however, this mobility will slowly expose losses that the banks cannot face.

The bank runs we have witnessed are only the inevitable last act of a tragedy that starts with a silent digital deposit bank walk. Insuring those deposits will not be sufficient, since even the insured deposits are leaving. Decreasing the short-term interest rate might not help either. If this decrease is perceived as temporary, it might have no effect (or even a reverse effect) on the long-term Treasury rate, possibly exacerbating the losses.

Paradoxically, the only policy that might save these banks is a serious downturn in the economy, which will decrease long-term rates and reduce bank losses. In other words, the Fed may need to crash the economy in order to fix its past regulatory mistakes. The time has come to update the regulatory view that takes the stability of deposits as given. The cost of ignoring this change is too high to bear.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.