Far before the collapse of SVB, I provided systematic evidence that banks appear to benefit from their directorships on Federal Reserve Banks. The fact that the Greg Becker, CEO of SVB, served as a director of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco only strengthens my argument that these directorships may be bad news for the Fed.

In 2018, a contested election took place for a directorship on the board of the San Francisco Fed. Two things were noteworthy about this election. First, given the Federal Reserve System’s call for more diversity of its directors following the financial crisis, it is noteworthy that a man won against a woman. Second, it is noteworthy that the winner was an executive officer of a bank under the direct supervision of the San Francisco Fed, while the loser was an executive of a national bank under the supervision of the OCC.

In hindsight, the San Francisco Fed must wish the woman had won. The man was none other than Greg Becker, President and CEO of SVB Financial Group and CEO of Silicon Valley Bank. The Federal Reserve must now explain how a bank it supervises and that was led by one of its own directors failed and how Greg Becker was able to make large stock sales just days prior to the failure of SVB.

I have long argued that the fact that bankers serve as directors of Federal Reserve Banks creates the appearance of a conflict of interest, if not an actual conflict. The Federal Reserve argues that directors provide valuable information that is useful for monetary policy. But information flows are rarely one-directional. Moreover, this argument ignores the fact that the Fed may, as in the case of SVB, be the main supervisor of its directors’ banks. In these cases, directorships allow banks like SVB to influence the governance of the very institution that is responsible for supervising them.

Whether this arrangement serves private bankers’ or public interests is a question that has been publicly debated at least since the 1930s and probably much earlier. It is time to re-inject some evidence into the debate.

In my (2017) paper “Good News for Some Banks”, I examine whether banks with Reserve Bank directorships appear to benefit from their positions.

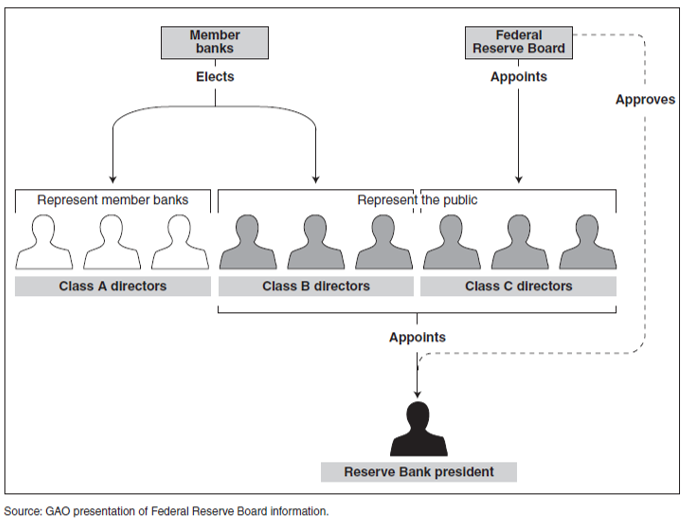

Figure 1: The Structure of Federal Reserve Bank Boards

Figure 1 shows how Federal Reserve Bank boards are structured after the Dodd-Frank Act. Just like a corporation, each of the Federal Reserve Banks has a board of directors. Each board has nine directors. The directors are divided into three categories. Three “Class A” directors represent the banking community. Three “Class B” directors represent the non-banking community. Three “Class C” directors are appointed by the Board of Governors. What is special about the three directors representing the banking community and the three directors representing the non-banking community is that they’re elected by member banks. So, six directors are elected by member banks. In addition, while the three Class A directors only need to represent the banking community, in practice, they are all bankers.

Do these boards matter? Just like in a corporation, the board is responsible for appointing the chief executive, the president of the Fed.

There are two main channels through which banks might receive private benefits from Class A directorships. The first is supervisory leniency. Although Reserve Bank boards are generally not directly involved in any supervisory decisions, the Government Accountability Office documents questions that arose during the financial crisis about the Fed’s treatment of banks that were connected to it through directorships, most notably Goldman Sachs.

Another potential private benefit for banks could be privileged access to information.

To examine whether banks benefit from Class A directorships, I assembled a variety of different data sets on the employers of Reserve Bank directors and the directors themselves. Because member banks elect both bankers and non-bankers, the fixed board structure of the Fed allows me to contrast differential benefits (or costs) of directorships for bankers and non-bankers.

In an event study around director election dates, I find that the market believes that Federal Reserve Bank directorships add value, but only for banks. The abnormal market reaction to the election of a banker to a Fed board is 0.99%. For non-bankers, the average market reaction is -0.57%. In cross-sectional regressions, I find the market reaction for Class A directors is higher when they are elected to the board of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and when the election takes place during the financial crisis. In contrast, the market reaction to class B directorships is negative during the crisis.

My analysis of insider trading behavior supports an information advantage story. On average A directors buy more shares in their employers while they sit on the board of a Fed than B or C directors. One notable example of a Class A director buying shares while serving as a Fed director is Jamie Dimon, who during his tenure as director of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York bought more than 860,000 shares in JP Morgan.

On average A directors also buy more shares while on the board of a Fed than otherwise. Furthermore, the market reaction to insider purchases of A directors is significantly more positive when they sit on the board of a Fed. In contrast, there is no differential market reaction to purchases by B and C directors when they sit on the board of a Fed. Consistent with the event study results, I find that the market reaction to insider purchases of A directors is higher when they sit on the board of a Fed during the financial crisis and when there is greater uncertainty about financial regulation.

The event study and insider trading evidence suggests there are informational advantages to Class A directorships. An analysis of enforcement actions suggests that banks with Fed directorships also anticipate supervisory leniency. The case of SVB suggests that further research is needed to uncover the relationship between Fed directorships and risk-taking behavior.

My results are consistent with the idea that private interest representation on Federal Reserve Bank boards may lead to private informational benefits and, possibly, private supervisory benefits for banks. While I explore alternative hypotheses, no other hypothesis fits the pattern of all the results I present as well.

Senator Dodd’s 2009 reform bill proposed to strip banks of their power to select Federal Reserve Bank directors. Although the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 does not contain such a provision, it does restrict class A directors from having a say in the selection of Fed presidents, as Figure 1 illustrates. In 2013 Senators Sanders, Bozer and Begich introduced legislation to remove banking executives from Fed boards. Representative DeFazio introduced a companion measure in the House.

Yet, nothing changed. Moreover, as I describe in a companion ProMarket article, my paper is not yet published.

These might be the strongest pieces of evidence yet that Class A directorships are valuable to the banking industry. In my paper, I show that service in the leadership of the American Banking Association (ABA), the largest and most powerful lobbying group for the banking industry, predicts whether a banker obtains a Class A directorship. Indeed, in my sample three percent of Class A directors simultaneously serve as directors of the American Banking Association. If Class A directorships are supported by the ABA, it is unclear how the Fed can reduce its reputational risk.

On March 23, 2023 Senator Sanders again introduced legislation to prevent big bank executives from serving on Federal Reserve Bank boards.

If history is any indication, this legislation is unlikely to pass. It is high time that academia starts increasing its efforts to hold political and regulatory power to account.

I declare that I have no conflicts of interest.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.