A new paper by Elisabeth Kempf from the University of Chicago looks into the performance of credit analysts who left to work for investment banks and finds that they were more accurate than their peers.

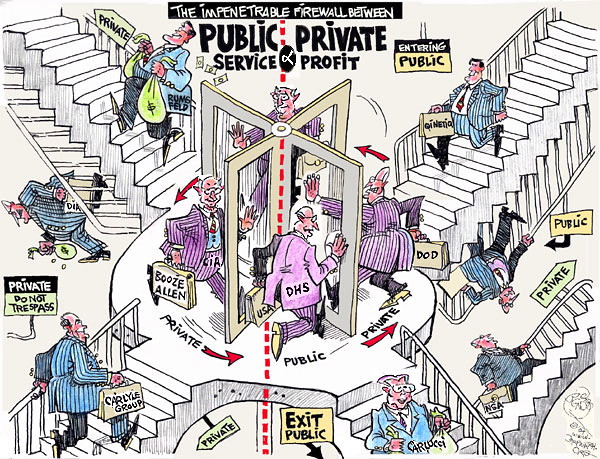

There is currently an intense discussion about the role of revolving doors in the public sector. This practice has been accused of being one of the main catalysts for regulatory capture, conflicts of interest, and excessively complex regulations. But what about private firms that play a regulatory role, such as credit rating agencies?

Former Representative Barney Frank, one of the architects of the Dodd-Frank Act, perfectly highlighted the potential problems in a 2011 interview with the Wall Street Journal: “You are rating someone and then you want to go work for them and make much more money—the notion that you would be critical of some entity and then hope they hire you goes against what we know about human nature.” Mindful of these potential conflicts of interest, the architects of Dodd-Frank required that firms disclose the names of analysts who left to work for firms they had previously covered. But if this practice is so corrupt, why do credit rating agencies allow it?

A new Stigler Center working paper by Elisabeth Kempf from the University of Chicago provides a possible answer to this puzzle: when it comes to credit rating analysts, the revolving door might not distort, but strengthen incentives.

Kempf, an assistant professor of finance at the Booth School of Business, created a dataset that tracks the career paths of 245 credit analysts at Moody’s, identifying those who joined an investment bank after working for Moody’s and those who did not leave or went to work for another employer (this she does using their LinkedIn profiles). She then links their career trajectories to the performance of 24,406 ratings issued for securitized finance securities by revolving and non-revolving analysts between 2000-2009, prior to the enactment of Dodd-Frank.

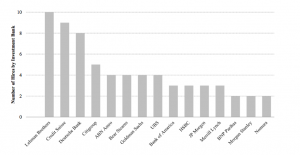

Of the 245 analysts Kempf tracks in her paper, 67 went to work for one of the major 20 investment banks, 94 left to work for other employers, and 84 stayed with Moody’s and were still working there as of December 2015.

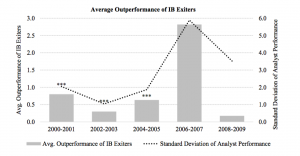

Kempf finds that the analysts who later left Moody’s to join investment banks outperformed non-revolving analysts who rated similar products during the same period. The revolving-door analysts were significantly more accurate, she finds, especially as they got closer to transitioning and as they rated more complex securities. Kempf also identifies 52 analysts who had previously worked at investment banks and notes that these did not perform very differently.

Kempf argues that one potential reason why revolving-door analysts outperformed their peers is that they have been working harder, attempting to develop their skills in order signal their abilities to potential employers. Consistent with this interpretation, she finds that analyst performance improves around news about improved employment opportunities in the investment banking sector.

These findings, she argues, are inconsistent with what’s often termed the “quid pro quo” interpretation of the revolving door, which views the revolving door as severely distorting the decision-making of analysts and regulators. This view has been presented over the years in numerous papers, dating back to Ross D. Eckert’s 1981 paper “The Life Cycle of Regulatory Commissioners.”

Opposite to the quid pro quo view is the “human capital” view, which argues that regulators and analysts are hired by firms they oversee because of their qualifications and expertise. According to this interpretation, analysts, regulators, and other monitors have a greater incentive to be stricter toward the firms their monitor, as a way to signal their professionalism to future industry employers. This view has also been the subject of numerous studies. For example, this 2014 paper by Sumit Agarwal, David Lucca, Amit Seru, and Francesco Trebbi.

So far, empirical evidence that supports either of these hypotheses has been scarce and inconclusive. In 2014, Ben Lourie of UCLA examined the phenomenon of sell-side analysts joining firms that they previously covered and found that revolving-door analysts alter their forecasts to become more optimistic about the firms that end up hiring them and more pessimistic about the prospects of rival firms, in a way that suggested they were attempting to curry favor with their future employers.

While on average revolving-door analysts do not perform differently when rating their future employers, Kempf does find an exception: during the last year at Moody’s, the performance of revolving-door analysts in rating the securities of the future employers starts to deteriorate just before they leave.

This, Kempf writes, is potentially consistent with the quid pro quo approach. It is also consistent with the findings of a 2016 paper by Jess Cornaggia of Georgetown University, Kimberly Cornaggia of American University, and Han Xia from the University of Texas at Dallas, which found evidence that revolving door analysts do inflate the ratings of their future employers before they switch jobs, as well as with the documented phenomenon that equity analysts are more optimistic about the firms that end up hiring them or appointing them as independent directors.

Kempf acknowledges that this discovery is consistent with previous studies that found that analysts are biased in favor of their future employers during the last year of their employment. However, she argues that instances where analysts rate their future employer before they move are rare, that this underperformance only applies to securities underwritten by their future employers, which represent only a small fraction of all the securities that revolving-door analysts rate, and that in general, revolving-door analysts were significantly more accurate than their peers in their ratings of securities unrelated to their future employers.

“Because only few ratings may be helpful to curry favors to future employers, but almost all ratings are helpful in signaling skill or building expertise, the positive effects of revolving doors can be economically sizable,” Kempf writes.

How well can these findings be translated to revolving doors in the public sector? This, says Kempf, depends on a number of factors: the visibility of individual performance signals, the importance of individual reputation, and the skill-intensity of the industry in which hiring firms operate. For some professions in the public sector, she notes, the transferability of the findings in her paper may therefore be limited, and further research would be needed to improve our understanding of what drives revolving door effects in different professions.