A recent working paper suggests that firms react to political risk, both passively by cutting investment and employment, and actively by ramping up lobbying efforts.

From Trump to Brexit, 2016 provided ample reason to revisit the age-old question of how changes in the political environment affect the economy. Specifically, how do political risk and uncertainty affect decisions by households and firms on investment, employment, and so forth?

It is by now well accepted that political shocks and instability are inimical to the long-term growth of developing economies and may also shape the macroeconomics of developed economies. Yet the quantification of political risk and its effects remains a daunting task.

In a recent working paper titled Aggregate and Idiosyncratic Political Risk: Measurement and Effects, Chicago Booth professor Tarek Hassan and co-authors Stephan Hollander, Laurence van Lent, and Ahmed Tahoun employ an innovative methodology to try to narrow the gap in our ability to measure political risks and how firms react to them. Their findings suggest that firms do indeed react to political risk, both passively by cutting investment and employment, and actively by ramping up lobbying efforts.

To understand their contribution, it is useful to start from the methodology. Hassan and co-authors looked at quarterly conference calls between managers of traded firms and analysts. They then measured how much time during the conversation was dedicated to talking about political issues and risks. The idea is that with firms who face relatively higher levels of risk and uncertainty due to political changes (say, a regulatory reform), either the analysts will ask or the managers will voluntarily dedicate more time to discussing the political environment. In other words, the ratio of political to non-political conversation in these conference calls is a proxy for the political risk faced by a specific firm.

To make such methodology work, Hassan and co-authors needed to find a way to code the conference call transcripts, so as to accurately measure what share of the conversation really relates to political risk. They did this by borrowing from computational linguistics, using an algorithm that learns which sequences of words are associated with political conversations and which with risk/uncertainty.

After gaining confidence that their measure really picks up firm-specific political risk, Hassan and co-authors moved to examine how companies react to such risk. Once managers who frequently alluded to political risks hang up the phone, do they behave differently than managers who were troubled less by political turmoil? The answer is yes, in more ways than one. First, firms that face more political risk tend to cut back on hiring and investments. This result was more pronounced when the specific political risks that were mentioned were government reform, health care, and the environment.

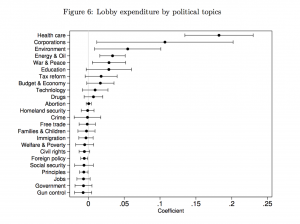

Second, firms also seemed to be actively managing their political risks, by lobbying more and donating more to election campaigns. Importantly, Hassan and co-authors broke down lobbying into topics and found that firms increase spending on lobbying specifically on the issues that were mentioned during the conference calls, rather than simply ramping up lobbying more generally.

To be sure, there could be some cheap or manipulative talk going on. That is, managers may mention political risk in the conference calls merely as an excuse for steps they would have taken regardless of the political environment; or they may be angling for political favors. While Hassan and co-authors find indications that such dynamics are indeed in play in some instances, the overall wealth of findings strongly suggests that political risk and uncertainty do play a real and not insignificant role in firm behavior. When firms discuss ProMarket’s post on Trump’s expected antitrust policy in their next quarterly conference calls, expect some actions to follow!