Even when antitrust enforcers and courts get it right when finding an anticompetitive infringement, they constantly end up imposing remedies that are inadequate to solve the problem they identify. A new paper tackles this issue by developing a novel framework for designing effective antitrust and regulatory remedies for the digital economy.

Policymaking in the digital world has never been hotter: hardly a week goes by without enforcers and legislators across the world either announcing new antitrust investigations or discussing new laws and regulations targeting big tech companies.

Yet, authorities’ track record in designing remedies that actually accomplish their stated goals is incredibly poor. For example, a large review of prohibitions against Most-Favored-Nation Clauses—which require businesses to extend to some companies the “best price” they offer to other suppliers—in the European travel sector concluded that almost no hotel knew that MFN clauses were banned or acted upon them. Similarly, Microsoft’s lack of implementation of a browser choice window—made following an investigation into Microsoft’s tying of Internet Explorer to Windows—went unnoticed for more than one year before it was fined in the EU. There has also been much debate about the alleged (in)effectiveness of the European Commission’s remedies in Google’s Android and Shopping cases.

The causes of such failures are many and multi-faceted. Yet, they likely share a common root in the fact that both antitrust scholars and policymakers were not trained to think about remedies as a stand-alone, important step in antitrust enforcement. There is a lot of discussion on how to determine when a company has broken the law, but little on what exactly is the ideal intervention to restore welfare. For example, the European Commission’s decisions against Google in the Android and Shopping cases run for 327 and 215 pages, respectively. Yet, out of those, 311 pages of the Android decision’s and 203 pages of the Shopping case are spent on establishing Google’s liability; only 3 and 4 pages (respectively) outline what Google should do to restore competition in these complex markets. Many calls for retrospective remedy assessments usually go unnoticed (not surprisingly, as no regulator wants to run the risk of an official assessment stating that it has done a bad job). As a result, remedies are largely understood as a one-off effort, usually a general prohibition. Understaffed regulators lack the resources to assess compliance and the procedural tools to adapt remedies over time.

In an article recently published at the Journal of Competition Law and Economics, we start to tackle this issue by developing a new framework to help with the design of effective antitrust and regulatory remedies for the digital economy.

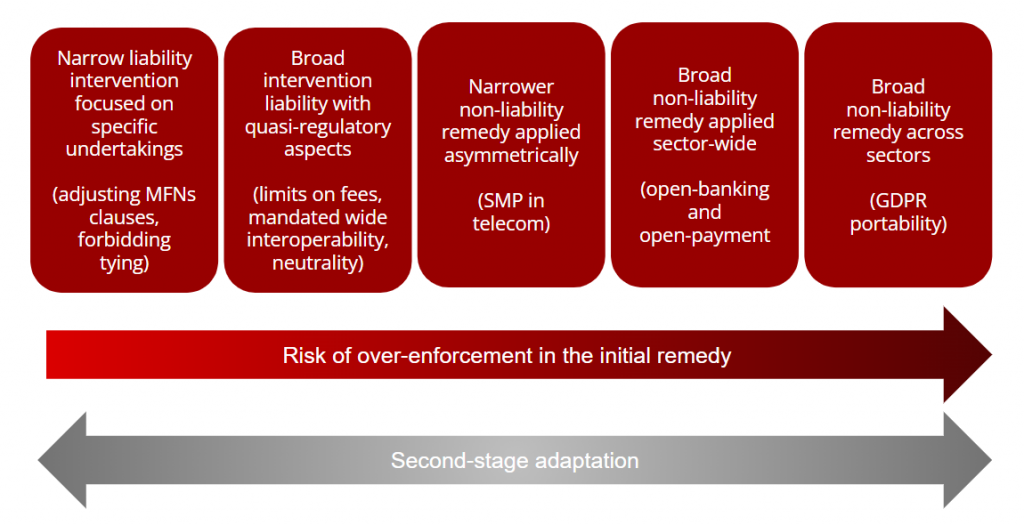

As new laws such as the European Digital Markets Act (DMA) and others come into force, the interaction between antitrust and regulatory remedies is only bound to grow. More importantly, these new laws will also expand the range of potential tools authorities can choose from when deciding how to remedy a given problem: from narrow, liability-based interventions focused on a specific company (a traditional antitrust remedy that can only be imposed after a company is found in violation of competition laws), up to broad non-liability-based remedies that apply across sectors (e.g., GDPR data portability that applies to all companies that handle personal data). With greater power, however, comes greater responsibility: this wealth of potential tools also increases the risk that authorities will err when attempting to pick the right remedy—either because they choose an intervention that is either too narrow or too broad. In order to minimize this risk of error, we build on Judge Easterbrook’s seminal work on the application of error-cost doctrine to antitrust to propose a novel, compounded error-cost framework for remedy design.

Our proposed framework acknowledges that even if authorities and courts get it right regarding the findings of infringement or decisions to intervene, they may end up imposing remedies that are inadequate to solve the problem they identify, so that the remedies themselves harm welfare. This means that there are compounded (doubled) error risks when one is thinking about remedy design, reflecting the uncertainty regarding the finding of infringement and the uncertainty regarding the right scope of the intervention imposed to remedy the conduct.

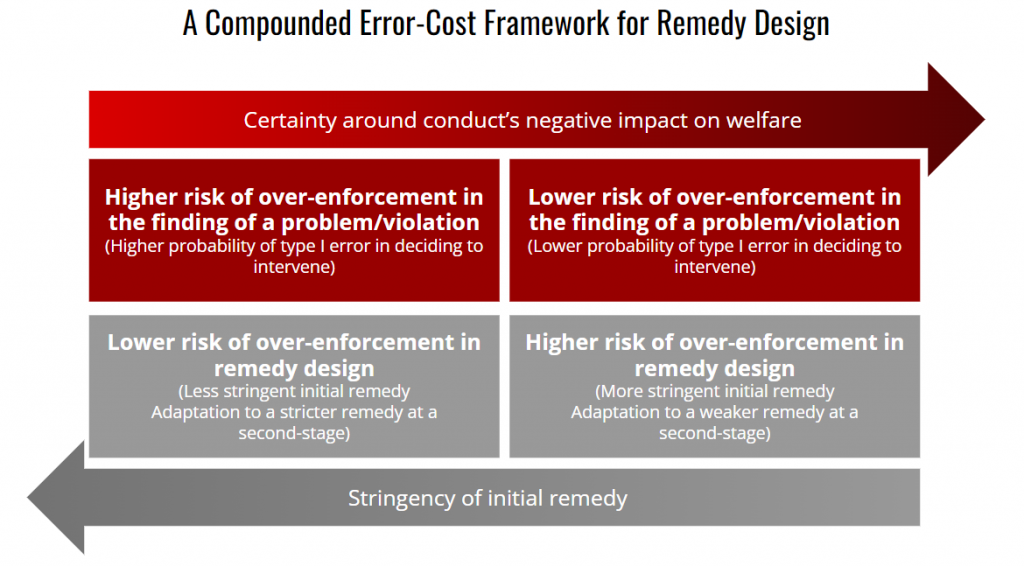

Thus, it is important to understand remedy design as another field open to over-enforcement (Type I) and under-enforcement (Type II) errors. This error-cost approach for remedy design implies evaluating how certain regulators are that they identified illegal conduct or a market failure that warrants public intervention, and then focusing separately on the potential errors at the intervention level (over or under-inclusive fixes). Authorities’ goal in this two-step process then becomes minimizing the overall risks of this compounded effect in designing an intervention given that they have decided to intervene.

As such, in defining the scope of remedies authorities must balance: (i) how certain they are that the violation took place, or that the conduct negatively impacts welfare; and (ii) how harmful the conduct is to market competition and/or to general welfare.

For example, if authorities are certain that an anticompetitive behavior has taken place (e.g., conduct is well-known to restrict competition, has no economic rationale and produces little efficiencies) and believe it has been very harmful to the market (e.g., allowed or maintained monopolization of a given sector) then they should start by imposing more stringent remedies, eventually risking over-enforcement. The opposite is also true: if authorities are introducing new theories of harm and assuming a risk of over-enforcement in outlawing an ambiguous conduct (Type I error in characterization of infringement), they should opt for narrower, less-risky interventions—otherwise, they would risk a compounded effect of two “over-enforcement” errors: an overbroad definition of infringement cumulated with overbroad remedies. They should then adapt the remedies as they obtain more information on how they have impacted market behavior.

In practical terms, this means matching a lower risk of over-enforcement in the finding of an infringement with a higher risk of over-enforcement in remedy design, and vice-versa.

Thinking about remedy design under this framework of minimizing a compounded risk is helpful for two reasons: first, remedy design is a non-binary process (unlike findings of infringements or decisions to intervene—either there is liability/intervention or there is not)and, as such, it is significantly better suited to minimization and fine-tuning; second, it highlights how remedy design should not be relegated to the last pages of a 300-page antitrust decision, but rather is a dynamic process that can and should be monitored and adapted over time as market conditions change. Changes in remedies should not be seen as regulators failing to do a good job, but rather as a necessary process of adaptation that help diminish information asymmetries between regulators and market agents. As such, we also need to develop specific processes and authorities must allocate personnel to accomplish this task.

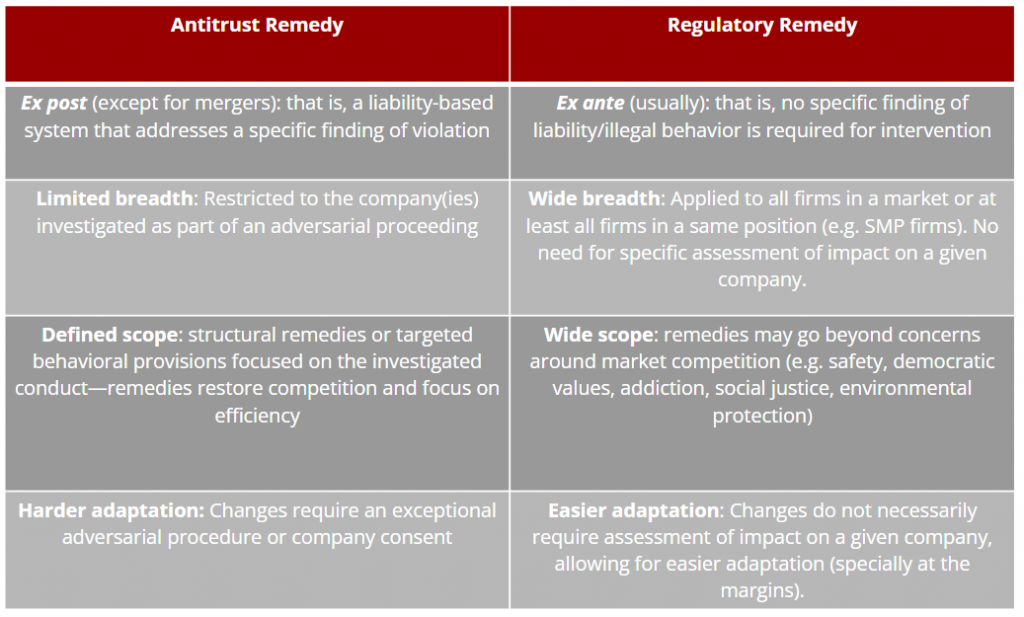

Yet, acknowledging this risk of compounded errors in remedy design is only part of the task of improving interventions in the digital world. Another connected but separate issue is how to allocate tasks between antitrust and regulatory interventions. We start by theoretically separating antitrust and regulatory remedies along four main variables: (i) requirements for imposition/liability; (ii) breadth; (iii) scope and (iv) easiness of adaptation.

A high-level analysis of these characteristics shows how regulatory remedies are more likely to be over-inclusive (Type I errors) than antitrust remedies: regulatory interventions do not necessarily require that specific companies are investigated and convicted of wrongdoing, usually apply to a larger number of players and may establish obligations that go well beyond restoring competition (the theoretical benchmark for antitrust remedies). Still, an important balancing exists even within regulatory remedies, as over-enforcement is more likely in broad regulatory prohibitions (e.g., all MFNs are banned in the hotel sector) than in narrower and more tailored regulatory interventions such as asymmetrical obligations imposed on players deemed as being gatekeepers or bottlenecks.

This relatively higher risk of over-enforcement in broad regulatory remedies over narrow antitrust remedies, however, should not be considered in isolation, but always in conjunction with the certainty over how much the behavior is harming overall welfare. In practical terms, this means that for a same level of certainty regarding the harmful impact of a given conduct, authorities should first consider whether narrow, liability-based interventions focused on well-defined companies will be enough to reestablish welfare. If these are deemed enough, then authorities should rely on antitrust enforcement and impose this narrow remedy. As the level of certainty that such narrow intervention is insufficient to reestablish welfare increases, authorities should move towards riskier interventions, normally more regulatory in nature. Authorities should then adapt these remedies over time—making them more or less strict—at a second stage and once they gather information on how their interventions are actually impacting market conditions.

Two final remarks are important. First, this framework does not require that authorities always start by imposing narrow antitrust remedies. If they are certain that such a narrow remedy would be sub-optimal—for example, because the conduct has broad effects on the market and has been very harmful to competition; because the adversarial, liability regime is too slow to intervene or because the problem is not one that can be addressed by the competitive process alone (e.g., disinformation or excessive data collection)—then they should accept higher risks of over-enforcement in the imposition of the initial remedy and start with asymmetric regulatory obligations or even broader interventions. What this framework requires is that when doing so, authorities justify why they are opting for this higher-risk intervention. In their justification, they should evaluate how much risk of over-enforcement they accepted in the finding of a violation and their level of certainty that a more targeted remedy will not be enough to reestablish welfare.

Secondly, it’s important to stress that this rationale applies to different phases of a given proceeding. Authorities are generally relatively less certain about the negative impacts of a given conduct when adopting interim measures than final rulings. Therefore, interim measures should be relatively (emphasis on “relative”) more targeted than final rulings.

As antitrust and other regulators become more empowered to address harmful behavior in the digital world, they also need to rethink the principles that will guide their interventions. Thinking about remedy design as a structured, dynamic process is certainly an important first step to ensure that the (long) list of failed remedies in antitrust and beyond does not continue to grow.

Disclosure: Both authors have previously acted as external counsel to digital platforms and companies operating in the electronic payments sector in Brazil (including Google, Facebook, Alelo, Bradesco, Cielo and Elo). Lancieri’s involvement ceased in 2015; Pereira Neto is still retained by these companies. This article, however, reflects solely our own independent judgment and it did not receive funding or was subject to any form of influence from outside sources. All errors are, of course, our own.

Learn more about our disclosure policy here.