The New Brandeisian version of American history presumes that there was a mid-20th century golden age of antitrust that was displaced by a misguided school of thought. Yet the nostalgia for a purported golden era of antitrust is misplaced in significant ways, and intellectual trends that challenged antitrust orthodoxy were crucially fortified by growing doubts about state regulation and concerns regarding foreign competition.

Editor’s note: The current debate in economics seems to lack a historical perspective. To try to address this deficiency, we decided to launch a Sunday column on ProMarket focusing on the historical dimension of economic ideas. You can read all of the pieces in the series here.

In 1964, William Orrick, head of the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division, remarked, “Antitrust is like the Mississippi. It just keeps rolling along.” A major bend in the antitrust river could be in prospect, however: Jonathan Kanter, the present-day successor to Orrick at the helm of the DOJ’s antitrust division, Lina Khan, the chair of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), and Tim Wu, special assistant to the president for technology and competition policy, are prominent critics of the antitrust status quo who have recently acquired “passports to power.”

History is helping to set the tone for antitrust reform. The most enthusiastic advocates of reform are known as “New Brandeisians,” harkening back to distinguished jurist and Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, who more than a century ago warned of a “curse of bigness,” notably echoed by Wu as the title of a 2018 book. Senator Amy Klobuchar (D-MN), who has introduced a “sweeping” 56-page antitrust reform bill to Congress, has fortified her case for change with a best-selling 624-page book on antitrust in which a majority of the chapters focus on history. When President Biden signed an executive order in July encouraging federal agencies to promote competitive markets, he said he was committing “the federal government to full and aggressive enforcement of our antitrust laws” following a 40-year experiment “of letting giant corporations accumulate more and more power.”

The New Brandeisian version of events presumes that there was a mid-20th century golden age of antitrust displaced with baleful consequences by a misguided school of antitrust thought linked with the University of Chicago. In a recent working paper, I argue this version of antitrust history is dubious. The nostalgia for a purported antitrust golden era is, for instance, substantially misplaced. Moreover, while the late 20th century antitrust counter-revolution is often blamed solely on the Chicago School, as implemented by the Reagan administration, growing doubts about the efficacy of government regulation and a dramatic surge in foreign competition played a key role.

Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), in an influential 2016 speech that according to Matt Stoller was “the first major talk by a politician on the problem of concentrated power over markets in decades,” referred fondly to an era when “(a)ntitrust law was real—and American corporations knew it.” According to Warren, the era began in the late 1930s when “antitrust enforcement took off” under the leadership of Thurman Arnold, head of the DOJ’s antitrust division, and continued through to the end of the 1970s. The intervening decades were, according to Klobuchar’s 2021 book on antitrust, “(t)he golden age of antitrust enforcement.” Khan, in a highly influential 2017 Yale Law Journal article, maintained there was “recognition that excessive concentrations of private power posed a public threat, empowering the interests of a few to steer collective outcomes,” and courts and antitrust enforcers applied the law accordingly. Wu, for his part, argued in his Curse of Bigness book “(t)he American enforcement of anti-monopoly laws reached its zenith in the 1960s” and maintained “(t)he peak of anti-monopoly enforcement coincided with a period of extraordinary gains in prosperity.”

What went wrong as the 20th century drew to a close? President Biden, in his remarks on his 2021 executive order, said that “Forty years ago, we chose the wrong path, in my view, following the misguided philosophy of people like Robert Bork, and pulled back on enforcing laws to promote competition.”

In invoking Bork, President Biden referenced what is for present-day antitrust reform advocates the key phase of antitrust history, oriented around the malign influence of Bork and, more broadly, the Chicago School of antitrust. The Chicago School argued that antitrust enforcers should forsake trying to protect competitors losing out to dominant rivals and attempting to safeguard democracy from concentrated private power. The focus should instead be on what the Chicago School treated as closely-related goals, enhancing consumer welfare and increasing economic efficiency. Bork, who is best known for his failed 1987 nomination to the Supreme Court, graduated from the University of Chicago before becoming a highly influential antitrust commentator while working as a law professor and serving as solicitor general and as a federal appeals court judge.

The Supreme Court explicitly invoked Chicago School commentary in 1977 in Continental Television v. GTE Sylvania, in which the court ruled, contrary to a decade-old precedent, that non-price restraints a manufacturer had imposed on distributors should not be governed by a “per se” rule where a court was to presume conclusively the conduct was unreasonable and therefore illegal. Then, in the 1980s, the market-friendly administration of Ronald Reagan drew heavily on Chicago School reasoning while revamping federal antitrust policy. This reputedly set a counter-productive path for ensuing decades. As Warren argued in her 2016 speech, “Bork’s framework limits antitrust thinking even today.”

The invocation of history by those advocating for antitrust reform has gone largely unchallenged. Closer scrutiny is merited, and the mid-20th century’s supposed golden age of antitrust stands out as a prime candidate for re-evaluation.

“THERE WAS A GENERAL PERCEPTION THAT ANTITRUST ENFORCEMENT OTHERWISE LAGGED DURING THE 1960S, WITH A RELUCTANCE ON THE PART OF THE KENNEDY AND JOHNSON ADMINISTRATIONS TO ANTAGONIZE BIG BUSINESS SEEN AS PLAYING A ROLE.”

Mid-20th century antitrust did feature eye-catching jurisprudence. During this era, the Supreme Court adopted per se antitrust rules in relation to a wide range of business practices. Antitrust enforcement, however, was uneven at best.

During the presidency of Harry Truman, cases launched during Thurman Arnold’s energetic tenure as head of the DOJ’s antitrust division remained active but antitrust only re-emerged fitfully following World War II. Eisenhower-era trustbusters were reasonably adventurous, particularly in relation to mergers. The Eisenhower administration launched, for instance, a series of merger cases where the Supreme Court delivered big wins for the government in the 1960s, including Brown Shoe Co. (1962),Philadelphia National Bank (1963), Pabst Brewing Co. (1966), and Von’s Grocery Co. (1966). There was a general perception, however, that antitrust enforcement otherwise lagged during the 1960s, with a reluctance on the part of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations to antagonize big business seen as playing a role.

Arguably, a by-product of the not-so-golden mid-20th century antitrust era was the prevalence of the sort of market power that current advocates of antitrust reform attribute to the Chicago-influenced corruption of antitrust. University of Chicago historian Gabriel Winant writes: “The postwar years of the 1950s and ’60s were the age of ‘monopoly capitalism,’ as the Marxists then called it, or, less polemically, an era of ‘administered prices.’” A blue-ribbon antitrust task force Johnson set up in 1967 and then ignored reported “Highly concentrated industries account for a large share of manufacturing activity in the United States.” In a 1966 column, famous newspaper humorist Art Buchwald forecast that by 1978, only two corporations would remain in the United States, that they would merge, and that when the resulting corporation sought to buy the United States, nothing more would happen than the Justice Department studying “this merger to see if it violates our strong anti-trust laws.”

While antitrust was not the potent check on business activity during the mid-20th century that current advocates of antitrust reform assume, antitrust was by no means irrelevant when the 1970s rolled around. Antitrust budget and staff levels increased and a national antitrust commission that President Carter established in 1978 recommended introducing a “no fault” approach to the antimonopoly rules in the Sherman Act of 1890 so violations could be established without proof of culpable conduct. Given antitrust law’s apparent 1970s vigor, why did a counter-revolution occur in the closing decades of the 20th century? For New Brandeisians such as Kahn, the answer is clear: “the failure to preserve competitive markets,” attributable to “contemporary antitrust enforcement,” can be traced back to “the Chicago School intellectual revolution of the 1970s and 1980s, codified into policy by President Reagan.”

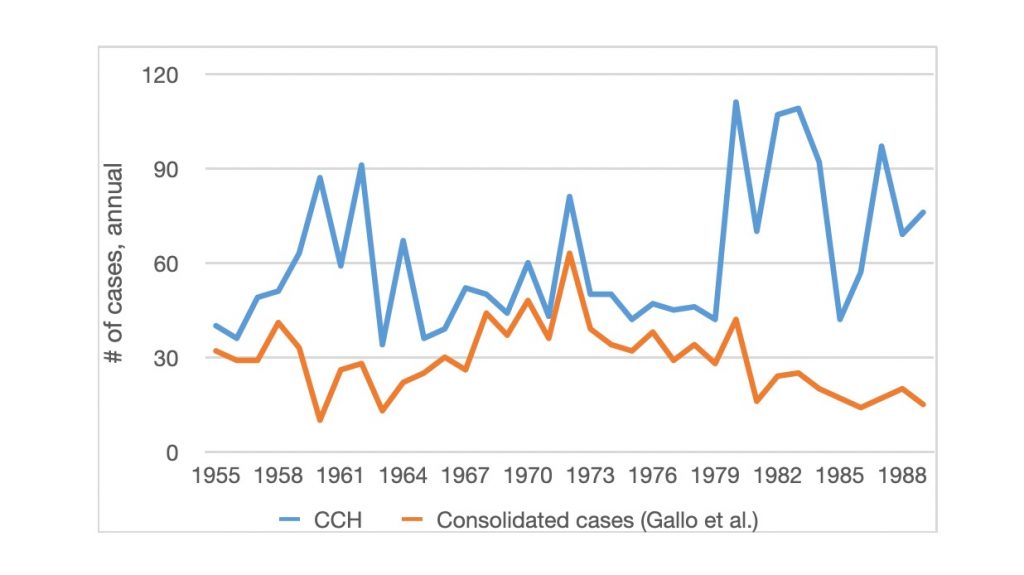

This version of events is too simplistic. Non-Chicago School variables contributed substantially to the reconfiguration of antitrust. Diminished faith in state regulation was one of these variables: The 1970s were a dismal decade for government, featuring America’s troubles in Vietnam, the Watergate political scandal, chronic federal budget deficits, and bungled efforts to control inflation and unemployment. Reagan swept to electoral victories in 1980 and 1984 as a critic of big government, and antipathy toward regulation, in turn, shaped antitrust policy during his presidency. As a senior FTC official explained in 1999, “A major part of that administration’s economic program was to reduce government regulation. Antitrust enforcement was perceived as being overly intrusive, out of control, and highly regulatory.” Even then, at least as measured by the number of DOJ antitrust cases summarized in the CCH Trade Regulation Reporter, more cases were on the go during the Reagan presidency than during the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s.

The rise of foreign competition also dovetailed with the intellectual trends in operation to reshape thinking about antitrust. With Europe and Asia rebounding fully from World War II and with transportation costs and tariffs falling, foreign competitors emerged in the 1970s and 1980s as a serious check on the market power of leading American firms. Examples of the American corporate elite side-swiped by foreign rivals included the “Big Three” automakers (Chrysler, Ford, and General Motors), their steel equivalents (Bethlehem, US Steel, and Republic), and consumer electronics pioneer RCA. Democrats as well as Republicans treated the trend as an antitrust game-changer. In a 1984 study of “The Attenuation of Antitrust,” Brookings Institution fellow Robert Katzmann identified “concerns about the increasing rigors of international competition” as an important cause of the rollback of antitrust then underway, thereby acknowledging the bipartisan nature of those concerns:

“The Reagan administration has been peppered with a generous sprinkling of Chicago-style academics and has therefore probably been more receptive to those changes than some other administration might have been, but the new perspectives on antitrust that are evident in this administration are by no means confined to the Republican party or to the conservative portion of the political spectrum.”

The antitrust counter-revolution associated with the Chicago School and the Reagan administration would evolve over the next quarter-century into what Khan has called “the relative stability of (an) antitrust consensus.” The historical account associated with current efforts to disrupt this consensus is partial at best and misleading at worst: Mid-20th century antitrust was not as vigorous as implied by current advocates of antitrust reform who invoke history. Moreover, whatever the merits of Chicago School reasoning, with doubts mounting about the efficacy of regulation and concerns growing that foreign competition had made an interventionist antitrust policy a luxury the United States could no longer afford, there was a congenial intellectual setting for the Chicago School critique of the mid-20th century version of antitrust.

Perhaps a major bend in the antitrust river would be beneficial now. Regardless, the historical account advocates of reform are relying upon should not be accepted at face value.

Author’s note: This post is based on “Turning the Antitrust Page,” to be published shortly in the Business History Review.

Learn more about our disclosure policy here.