For the majority of America’s regulatory history, the problem of employer monopsony was understood as a competition policy issue that required direct government-wide labor market intervention by expert agencies and commissions with industry-specific expertise. To address labor market concentration today, a similar “whole-of-government” approach is required.

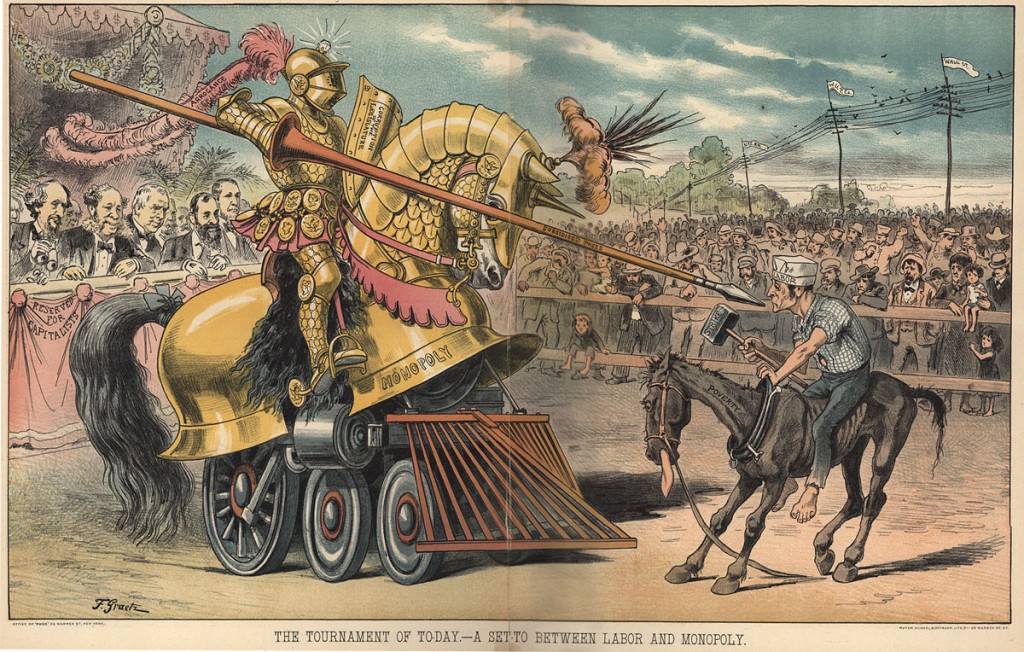

Does antitrust have a labor market problem? The last few years have seen growing interest among academic scholars in the causes and effects of concentration in US labor markets. Concurrently (and not unrelated), there has been an explosion of interest among policymakers and the general public in the impact that firms with market power may have on wages and working conditions. What do the data say regarding employer concentration and its effect on workers? Is antitrust in its current form equipped to address issues related to labor market power? In attempt to answer these questions and more, we have decided to launch a series of articles on antitrust and the labor market.

Since at least 2015, antitrust enforcers have unified behind a dramatic turn: tackling employer dominance and cartels. A key motivation was mounting empirical evidence of labor market concentration, wage effects from underregulated employer consolidation, and pervasive employer use of labor market restraints. Current research shows the average American labor market to be highly concentrated, and going from the 25th to 75th percentile of concentration is associated with lowering wages by 5 to 17 percent. Mergers can reduce wage growth and wage rates by 4 to 5 percent, as well as overall lifetime consumption by around 6 percent. Up to 40 percent of working Americans have been subject to non-compete agreements in their careers, and 58 percent of major franchisors’ contracts include no-poaching provisions, limiting worker mobility to seek higher wages and benefits.

But the new labor antitrust turn raises new and unresolved questions about antitrust’s role in labor market regulation and how that regulation coheres with competition policy. First is whether our current antitrust doctrine, agency practice and expertise, and interagency infrastructure are sufficient to challenge employer monopsony, or buyer power, and how. But a deeper, second set of questions concerns the nature of the challenge itself: Will labor antitrust require reorienting our current competition policy goals? Should antitrust prioritize worker over consumer welfare where they conflict? Does the labor antitrust turn compel moving the antitrust project beyond efficiency goals to integrate analysis of wealth transfers, inequality, and macroeconomic policy into enforcement?

While these questions remain unresolved, treating labor market regulation as a competition policy issue is not new. What is new is the pretense in much of the current antitrust literature and enforcement that employer monopsony should be addressed under narrow efficiency-based goals with significant antitrust agency and judicial discretion to formulate decision rules and balance competing welfare considerations in their enforcement and remedies. In fact, for most of our regulatory history, employer monopsony was understood as requiring a government-wide effort of direct labor market intervention by expert agencies and commissions with industry-specific expertise monitoring production and pricing as well as wage rates and labor disputes to achieve micro- and macroeconomic policy goals, primarily outside the purview of judicial administration. From the Interstate Commerce Commission through more expansive administrative regulation of industry price- and wage-setting through the 1970s, we have a long tradition of policing as inextricable employer dominance, production, and workers’ wages to restrain accumulated private power.

Aggressive, government-wide regulation of employer monopsony makes sense for two reasons. First, the sources of employer monopsony are not limited to market power they acquire by committing antitrust violations, but include natural labor market frictions and institutional factors—whether through government institutions and legal entitlements or the existence (or lack) of labor market institutions like unions. And second, regulating monopsony to avoid its adverse effects on wage rates and employment levels requires balancing competing policy goals that, relative to expert agencies, commissions, and arbitral boards, courts of general jurisdiction have neglected and lack clear precedent and expertise in performing. This is in no small part because regulation of employers’ labor market power through resolving and regulating pricing and wage rate disputes has been predominantly administrative with limited judicial involvement and significant deference to administrative findings. That rich regulatory history offers a wealth of lessons for rebuilding a robust, “whole-of-government” administrative infrastructure to sustainably tackle employer monopsony through competition policy.

The regulatory institutions that once formed the core of our administrative state intertwined regulation of concentrated industries with labor market supervision well into the early 1980s. Indeed, until the deregulatory Reagan era, modern regulation of dominant and oligopsonistic employers viewed antitrust and labor policy as complements rather than substitutes: ensuring efficient production involved government regulators easing labor’s militancy into cooperation as critical stakeholders by actively supporting worker-led institutions as part and parcel of a broader competition policy. This involved a range of more and less interventionist tools depending on industry conditions and broader economic crisis management goals during depressions, recessions, and war, including everything from direct, government-enforced “codes of fair competition” (or industry-specific codes that fixed prices and wages), to government-administered industry-wide boards regulating prices, wages, and labor disputes, to government-supervised collective bargaining setting wage patterns sector-wide to relegating employment bargains to private ordering.

“FOR MOST OF OUR REGULATORY HISTORY, EMPLOYER MONOPSONY WAS UNDERSTOOD AS REQUIRING A GOVERNMENT-WIDE EFFORT OF DIRECT LABOR MARKET INTERVENTION BY EXPERT AGENCIES AND COMMISSIONS WITH INDUSTRY-SPECIFIC EXPERTISE.”

At the launch of the trust-busting era, President William McKinley established the Industrial Commission (1898-1902) to investigate and make recommendations regarding industry-wide impacts of industrial concentration and railroad pricing on labor markets. President Theodore Roosevelt is credited with heeding those recommendations not only through his recognized role as Trustbuster-in-Chief, but also through establishing industry-specific tripartite boards—with representatives from government, employers, and workers—to coordinate production quotas and reinforce labor market institutions as counterparties to manage labor unrest. For example, Roosevelt established the Anthracite Board of Conciliation in 1902 to stabilize anthracite production and consolidate United Mine Workers’ power to better ensure higher wages and avoid strike disruptions.

While Congress passed the Clayton Act (1914) and Norris-LaGuardia Act (1932) to exempt labor combinations from the antitrust laws, government regulation of labor competition through regulating dominant employers continued through the Mediation Commission (1917), the National War Labor Board (1918-1919), the War Labor Policies Board (1918), the National Industrial Conference (1919), the Railway Labor Act (enacted in 1926), and the National Industrial Recovery Act (1933), which recognized “codes of fair competition” within concentrated industries to stabilize production and established the first federal labor protections for collective bargaining and codes for determining labor standards absent collective agreements.

The National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA)’s regulation of labor market competition evolved industry-by-industry, with some industries devising codes administering price and wage rates, others establishing separate boards for pricing and handling labor and wage disputes (in steel, automobile, petroleum, and textile production), and others never developing effective labor boards, relying on the strength of unions’ involvement in code-making. Donald Richberg, the NIRA’s co-author, explicitly viewed the competition codes’ purpose as recognizing “that the chief beneficiaries and customers of industry are the workers themselves,” and “their right to participate in shaping the policies of industries which vitally affect their lives.”

After the Supreme Court struck down the NIRA in Schechter Poultry v. United States (1935), Congress passed the National Labor Relations Act (1935) to secure workers’ countervailing power against employers, and government regulation of employers’ labor disputes and wage rates continued through administering competition policy and production controls, including through the National War Labor Board and the Office of Price Administration in the 1940s, the Price Stabilization and Wage Stabilization Boards in the 1950s, President Kennedy’s Council of Economic Advisors’ wage-price “guideposts” in the 1960s, the Pay Board and Price Commission in the 1970s, and the Council on Wage and Price Stability and Pay Advisory Committee in the 1970s. Until President Reagan folded the Council on Wage and Price Stability into the Office of Management and Budget in 1981, it, along with the Pay Advisory Committee, monitored and recommended voluntary wage-price restraints while evaluating inflationary and other economic effects of government-wide agency regulation of output decisions.

Collectively, these regulatory bodies regulated prices and competition in dominant American industries while also monitoring and recommending industry-wide wage rates, mediating labor disputes that threatened production, and even setting wage increase pass-through rates to consumer prices based on equity and efficiency considerations. The mutual reinforcement of government and labor market institutions during this period were critical contributors to lifting workers’ wages, ensuring robust employment opportunities, and reducing inequality. The Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division also played a role from administering the NIRA on, serving as an early enforcer of the NIRA’s codes of fair competition, including the labor codes, to ensure that “competitive conditions” were maintained in labor markets. The Division was also staffed with government regulators and experts trained in Institutional Economics and in administering industry-wide price and wage standards.

Deregulation, beginning with the Reagan administration, dismantled this century-long infrastructure integrating wage-bargaining and competition-related regulation, gutting the Executive Branch’s regulatory base that had developed industry-specific, interdisciplinary social scientific expertise on employer monopsony’s effects on workers. A key component of the deregulatory agenda was diverting industry-focused competition policy that coordinated between labor and management interests in regulating price- and wage-setting to non-interventionist, generalized competition enforcement under the purview of the DOJ and Federal Trade Commission (FTC). This diversion confined the goals and expertise of competition agencies’ policies and enforcement to ignore labor market regulation goals and worker welfare (with the exception of agencies regulating in a diminishing number of industries, like railroads). Whereas prior competition regulators were steeped in institutional economics and industrial relations, and had direct experience with and knowledge of repeat industry players, unions, and wage-bargaining negotiations when regulating industry production decisions, the antitrust agencies focused on applying Industrial Organization economics to ascertain price effects of firm conduct, almost exclusively in product markets and under a consumer welfare standard. Thus, with the dissolution of prior competition regulatory schemes, questions of how to regulate competition to ensure efficient production were severed from worker welfare analysis.

This cleavage is at the core of labor antitrust’s current challenges in regulating employer power. We now know that employer monopsony is prevalent even in unconcentrated markets, where low labor supply elasticities persist due to search frictions, mobility costs, heterogeneous preferences, and weak labor market institutions. But the legacy of the deregulatory era is a hollow regulatory infrastructure to police that power. Specifically, the antitrust agencies’ more circumscribed methods and lack of labor market expertise—whether in lacking personnel with labor economics, industrial relations, or other social scientific training or in the utter lack of information-sharing and coordination with labor agencies in analyzing the labor market effects of employers’ anticompetitive conduct—significantly hampers their ability to assess employer monopsony and design remedies to reduce it. For example, the agencies have yet to acknowledge or integrate economic evidence of monopsony that accrues to employers due to labor market frictions (such as search costs, information asymmetries, and more) and weak labor market institutions (such as networks of legal protections and anemic union density that benefit employers). And proper diagnoses of the nature and scope of employer monopsony is merely the first step. Because employer monopsony is not exclusively sourced in labor market concentration, barriers to entry, and overt anticompetitive conduct, properly remedying it will take more than restoring competition alone.

Ironically, another challenge of tackling employer monopsony under our current, shrunken regulatory—or deregulatory—footprint is the legacy of administrative regulation itself. Because regulating wages and competition in labor markets has occurred, if at all, outside the courts in price and wage stabilization boards, commissions, or through private ordering in the form of collective bargaining administered through labor boards or arbitral tribunals, courts of general jurisdiction have limited precedent and expertise to evaluate or remedy employer power. Antitrust courts thus have to navigate new claims against employers without federal common law guidance on how to consider worker welfare and labor market effects as a competition policy matter, yielding incoherent and highly unpredictable outcomes for workers. Thus, labor antitrust jurisprudence has been muddled: courts have been uncertain about whether and how to balance labor market harms against product market benefits, and whether and how to balance worker and consumer welfare if they are found to conflict. When courts review merger settlements under the Tunney Act-required “public interest” standard, they fail to correct for any adverse labor market effects of negotiated remedies, even when unions intervene.

Without clearer doctrine, more robust agency expertise, and interagency solutions that draw on labor regulators’ knowledge and expertise, efforts to regulate labor market competition can worsen rather than improve outcomes for workers. For example, the court-administered breakup of AT&T intended to restore competition in telecommunications markets devastated worker earnings, reducing union density from 56 to 24 percent post-breakup, primarily by disrupting industry-wide pattern bargaining the Communication Workers of America (CWA) fought decades to achieve, decimating long-standing collective bargaining relationships, increasing the CWA’s coordination and transaction costs with the new regional employers, and losing the benefits of prior government regulators’ involvement that supported workers’ countervailing power against AT&T’s monopsony.

I and others have put forward a suite of doctrinal and legislative proposals to clarify when employer monopsony, agreements, and mergers violate the antitrust laws as a necessary component of establishing the legal contours of a new labor antitrust. These include establishing clearer and broader metrics for reviewing the labor market effects of mergers, clarifying contradictions in applying a consumer welfare analysis to labor antitrust claims, reforming our understanding of the effects of employers’ vertical agreements in both product and labor markets on workers, and stronger and more robust remedies to employer dominance. But without robust labor market institutions in government and labor markets themselves, truly remedying employer monopsony will remain elusive. Establishing clearly-defined competition policy goals in regulating labor markets and aligning our regulatory infrastructure to meet them is our biggest anti-monopsony challenge yet. But our longer regulatory history of using competition tools to shape labor market outcomes is instructive. It reveals that cohering competition and labor policy through better integrating labor and antitrust agency policymaking, expertise, and enforcement through interventionist government administration that bolsters workers’ institutions and their involvement in negotiating higher wages is consistent with and can further the goal of sustainably reducing employer monopsony. As both our regulatory history and President Biden’s recent Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy recognize, a “whole-of-government” approach is required.

Learn more about our disclosure policy here.