Since the Civil War, dominant firms have widely and repeatedly used exclusive agreements to exert, expand, and fortify their market power. History shows that the law can be used to ban these agreements.

Editor’s note: The current debate in economics seems to lack a historical perspective. To try to address this deficiency, we decided to launch a Sunday column on ProMarket focusing on the historical dimension of economic ideas. You can read all of the pieces in the series here.

Throughout history, monopolists have been able to implement a myriad of unfair tactics that fortify and extend their dominance. Among those, exclusive deals have been a critical legal tool for dominant firms to obtain and maintain control over a market.

Exclusive deals are contracts, implied agreements, or asserted practices that force dependent firms to engage exclusively with a firm. These contracts restrict the freedom of customers, distributors, and suppliers to conduct business with a corporation’s rivals. Rather than arising from an equal bargaining process, these agreements are often the result of a dominant firm imposing exclusivity on a smaller company merely because of their superior bargaining position and market power. Consequently, exclusive deals can block or marginalize a dominant firm’s rivals and permit them to unfairly perpetuate their market position.

Today, judicial policy favoring increased deference to corporate conduct has eroded so much of Congress’s efforts to limit exclusive deals that a company like Google can control 95 percent of the mobile search market predominantly through the use of exclusive contracts preventing smartphone manufacturers and wireless service providers from installing rival search engines. Dominant firms like Apple can use exclusive deals to limit the availability of parts for their products to inhibit the ability of third-party repair shops or consumers to be able to repair their products. Mylan, the maker of EpiPens, has used exclusive deals as a means to entrench its monopoly and prevent new and cheaper EpiPen-like devices from entering the market.

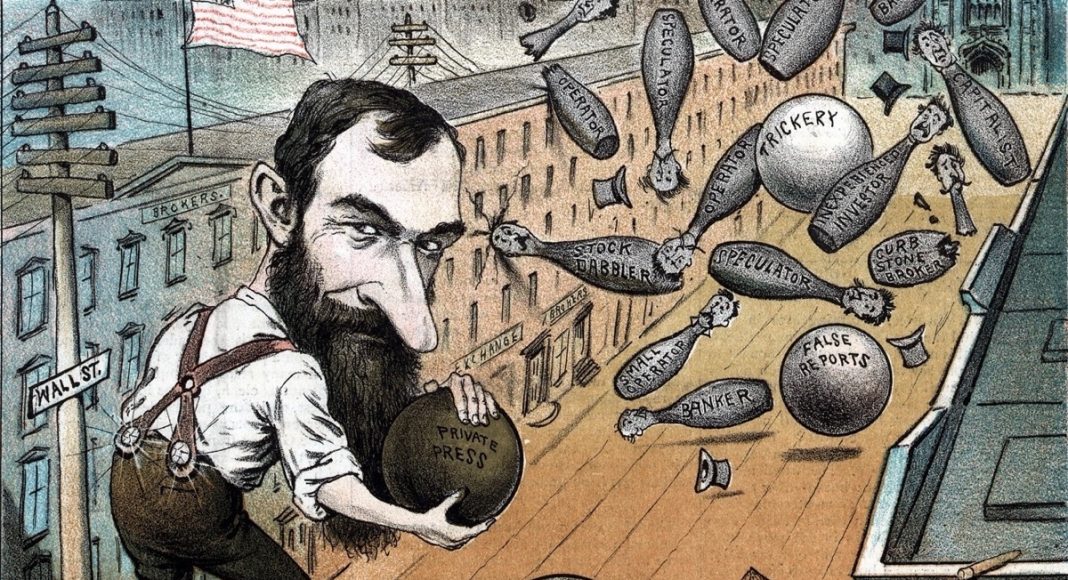

Exclusive deals have been particularly nefarious since the dawn of America’s industrial age. Since the Civil War, dominant firms have widely and repeatedly used exclusive agreements to exert, expand, and fortify their market power. These legal instruments were also an essential mechanism for some corporations to monopolize an entire industry and exert their economic dominance to impair, abuse, and destroy smaller firms.

For example, Western Union, the dominant 19th-century telegraph provider that controlled over 90 percent of the US market by 1866, took advantage of anemic federal policy and embraced exclusive deals as its primary weapon of choice to monopolize the telegraph market. Western Union’s extensive usage of exclusive deals in the late 19th century and the emulation of its business practices by other dominant firms like cigarette manufacturing and telephone service can illustrate why exclusive deals need to be prohibited.

Beginning in the 1840s and ‘50s, various states began to enact laws (known as incorporation laws) that specifically encouraged the creation of telegraph companies to harness and experiment with a technology that could potentially change every facet of society. Similar to modern technologies such as operating systems or social networks, the electromagnetic telegraph was significantly affected by scale economies. In general, the larger the network, the harder it was for rivals to enter and compete in the market.

Because loose state incorporation laws lowered the legal requirements to create a telegraph company, they were an affirmative policy by states to create a high degree of competition in the industry. However, Western Union throughout the late 1800s inked hundreds of exclusive agreements with railroad companies, the other industrial titans of that era, to be able to exclusively erect telegraph lines along railroad tracks (known as rights of way). Western Union realized that these exclusive right of way agreements radically scaled its operations to crush rivals and subverted the intent of loose state incorporation laws by increasing barriers to entry for rival telegraph companies. Western Union’s agreements prevented and deterred competition since many rivals were not able to obtain sufficient economies of scale to be a viable business.

After acquiring the corporation, archetype robber baron and financier Jay Gould boasted to a Senate Committee in 1883 that Western Union’s exclusive contracts made it “perfectly impracticable” for any competitor to subvert the company’s dominance. Prominent members of Congress, like Senator John Sherman, who would eventually write the nation’s first antitrust law in 1890, viewed Western Union’s dominance as a result not of its investments in research and development or its technological superiority, but of its prolific usage of exclusive agreements. Congress did enact federal regulation that ostensibly made such deals illegal, but courts struggled for decades to condemn these exclusive agreements. Western Union would continue to use exclusive agreements well into the 20th century.

During the 1850s, Western Union would also use exclusive deals with the Associated Press to monopolize Americans’ new hunger for breaking news after the Civil War.

The New York Associated Press (NYAP) was America’s most powerful news broker during the 1850s. The organization was a related predecessor to the modern Associated Press. It provided news reports to more than 30 percent of all newspapers, four times more than its closest rival.

Western Union saw an exclusive deal with the NYAP as a means to prevent rival telegraph operators from accessing a large user revenue stream and economies of scale. The NYAP saw exclusivity with Western Union as a means to insulate itself from competition and provide itself with an immense competitive advantage to widely distribute its news to the public that, in practical terms, could not be replicated. In 1856, the companies entered into an exclusive agreement that provided the NYAP the exclusive use of Western Union’s wires and other facilities to transmit news in its geographic operating area.

Western Union would also enter into sweeping exclusive contracts with other Associated Press affiliates. Western Union’s 1867 contract with the Western Associated Press, another predecessor to the modern AP, even included a clause that required restrictions and removal of news-based criticisms of Western Union. The exclusive pacts effectively allowed the corporation to act with impunity without public oversight and anointed Western Union as an “overlord” of the news. The agreement allowed the two corporations to dictate the terms for the content and telegraph rates for any new rival newspaper.

These agreements were enormously successful for Western Union and were destructive for the welfare of both industries. Newspapers that did not adhere to Western Union’s or AP’s demands were quickly excluded from using their systems—many went out of business. An 1874 Senate investigation bluntly concluded that Western Union’s exclusive agreements “amalgamate[d] rival [telegraph] lines, and thereby end[ed] all competition, and reduce[d] the press to entire subjection to its power.”

“exclusive agreements were by no means limited to the telegraph, railroad, and news industries. Other dominant corporations in the tobacco and telephone industries also extensively used exclusive deals to cement and extend their monopoly power.”

During this time, exclusive agreements were by no means limited to the telegraph, railroad, and news industries. Other dominant corporations in the tobacco and telephone industries also extensively used exclusive deals to cement and extend their monopoly power. American Tobacco, a monopoly with control over almost every aspect of the cigarette industry (and eventually broken up by the Supreme Court in 1911), used exclusive deals in 1890 with machine manufacturers to maintain its dominant position. American Tobacco’s exclusive deals were so critical they were called “the principal factor in the extraordinary success” of the company by the Bureau of Corporations, a predecessor of the FTC, in 1909.

In 1881, AT&T entered an exclusive deal to purchase only Western Electric equipment in exchange for Western Electric to exclusively sell to “Bell-licensed companies.” United Shoe had its coercive agreements upheld by the Supreme Court in 1913 and 1918. In 1917, the largest first-run exhibitors with 100 theaters formed a cartel and used their bargaining power to impose exclusive deals on movie producers.

Despite the known adverse effects of exclusive contracts, federal courts routinely permitted them until Congress decided to explicitly intervene, opening legal avenues for aggrieved parties and changing how businesses operated. Congress enacted the Sherman Act in 1890, as well as the Clayton Act and the Federal Trade Commission Act in 1914. Importantly, Section 3 of the Clayton Act prohibited exclusive deals for goods that “may be to substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly in any line of commerce.”

These statutes represented Congress’s affirmative steps to restrict and inhibit certain corporate conduct so that a firm’s operations are properly aligned with publicly acceptable values and structure the marketplace so that firm rivalry is based on investments in operations and the creation of high-quality products rather than exclusionary contracts or other unfair tactics. After 1914, a gradual crackdown on exclusive deals began. In particular, the deferential language from Section 3 of the Clayton Act, which prohibited exclusive deals if they “substantially lessened competition,” became critical to restraining the dominant power of monopolies from enacting exclusive deals and significantly enhanced the ability for litigants to challenge the usage of these agreements to the present day.

But it took until a 1949 case known as Standard Stations for the Supreme Court to fully enact Congress’s command to limit the use of exclusive deals. The court did this by enacting a rule, stating that an exclusive dealing arrangement would be illegal when a plaintiff demonstrates “proof that competition has been foreclosed [by the defendant] in a substantial share [of the market].” In this case, the court deemed a substantial foreclosure of competition existed with an exclusive dealing agreement from a firm with 23 percent market share closing off almost 7 percent of the geographic market to rivals. Although Congress limited the application of Section 3 of the Clayton Act to the sale of goods or commodities, the Supreme Court’s rule inhibited the usage of exclusive deals by dominant firms by simplifying the litigation process.

However, in a series of decisions between the 1960s and 1980s, the Supreme Court abandoned strict stance on exclusive deals it established in Standard Stations and adopted a complicated “rule of reason” test that incorporates a multitude of factors and economic analysis that it previously disowned in Standard Stations and was, in fact, never intended by Congress.

While there have been notable victories against monopolists using exclusive deals since the Supreme Court changed its analysis, the Court’s shift away from its Standard Stations holding caused the use of these agreements, even by monopolists, to enjoy a very defendant-friendly legal standard. Even when monopolists use exceptionally nefarious exclusive deals, public and private antitrust enforcers are required, despite the historical record showing the clear harms of these agreements, to engage in repeated and protracted lawsuits.

Despite the Supreme Court’s decisions to recede from the rule it established in Standard Stations, the FTC still has broad powers that can fix this situation without the need for intervention from Congress. In 1914, Congress granted the FTC broad rulemaking authority. Congress granted the FTC such broad powers as an explicit means to create an adaptive agency capable of utilizing its expertise to protect the public from dominant corporations and harmful business practices that prevent firms from competing fairly.

In the spirit of revitalizing the Supreme Court’s Standard Stations holding, the FTC should prohibit dominant firms from using exclusive deals by using its broad rulemaking authority to interpret “unfair methods of competition” in Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act. By employing congressionally delegated powers, the FTC under the new Biden administration can use existing law to prohibit an essential tool of monopolization and create a fairer marketplace.

Left unchecked, dominant firms will continue to use exclusive deals to entrench their market position, supplant competition, and coerce smaller firms into working exclusively with them. There are legal mechanisms available to restrict and prohibit these legal instruments. History shows that the law can be used to ban these agreements. The FTC can take action to do so now.

References

- Menahem Blondheim, News over the Wires: The Telegraph and the Flow of Public Information in America, 1844-1897, 108 (1994).

- Menahem Blondheim, The Click: Telegraphic Technology, Journalism, and the Transformations of the New York Associated Press, 17 Am. Journalism 27, 46 (2000).

- Allan M. Brandt, The Cigarette Century: The Rise, Fall, and Deadly Persistence of the Product that Defined America 39, 266 (2007).

- Gerald W. Brock, The Second Information Revolution 37 (2003).

- Michael Conant, Antitrust in the Motion Picture Industry 24 (1960).

- Alvin Harlow, Old Wires and New Waves: The History of the Telegraph, Telephone and Wireless 331–32 (1936).

- David Hochfelder, The Telegraph in America, 1832-1920, 39, 40 (2012).

- Jonathan M. Jacobson, Exclusive Dealing, “Foreclosure,” and Consumer Harm, 70 Antitrust L.J. 311, 317 (2002).

- Richard R. John, Network Nation: Inventing American Telecommunications 91, 95, 101, 120, 146 (2010)

- Richard R. John, Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse 7, 47, 49 (1995)

- Frank Parsons, Telegraph Monopoly 83 (1899).

- Paul Starr, The Creation of the Media: Political Origins of Modern Communications, 183-84 (2005).

- Joshua Wolff, Western Union and the Creation of the American Corporate Order, 1845–1893, 253-54 (2013).

Disclosure: Daniel A. Hanley is a policy analyst at the Open Markets Institute, which along with 36 other organizations and scholars petitioned the FTC to use its rulemaking powers to prohibit exclusive contracts.